Giacometti’s Crumbs

The Decorative Art’s of Alberto Giacometti

“The more you fail, the more you succeed. It is only when everything is lost and — instead of giving up — you go on, that you experience the momentary prospect of some slight progress. Suddenly you have the feeling — be it an illusion or not — that something new has opened up.” — Alberto Giacometti

Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) was somewhat unusual in that, at a time when there was a chasm between the fine and decorative arts, with the latter looked down upon as somehow inferior or lacking merit, he ignored naysayers, and, throughout his illustrious career, supplied vases, furnishings and lamps to a select coterie of decorators and collectors who shared and appreciated his unique aesthetic vision. It’s perhaps worth noting, that such commissions originated purely as a result of economic necessity, and one wonders whether this extraordinary body of work would have come to fruition, and for that matter, whether the trajectory of decorative arts would have changed entirely, had Giacometti been under the patronage of a Medici like benefactor from the outset. Luckily for us, the young artist needed to pay his rent, and as a result, he left an extraordinary body of work, that, unencumbered by binary labels, manages to bridge the worlds of art and design, defying, to a large extent, categorisation. Fundamentally, Giacometti considered what he referred to as “utilitarian objects”, as being no different to any other artwork, and approached them with the same passion, gusto and honesty as he did his sculptural endeavours. As a character he was nothing if not forthright and to the point, and as such, in a 1962 interview with critic André Parinaud (1924-2006) he explained sincerely, “in order to survive I accepted to make utilitarian anonymous objects for a decorator of the period ... I had tried as well as possible to make, for example, vases, and I was conscious that to work on a vase as if a sculpture, then there was no difference between what I would call a sculpture, and what was, in fact, an object — a vase !” Throughout the 1930s this artificial construct between les beaux arts and utility proved a constant source of chagrin, as Giacometti struggled with the age-old question of what constitutes art proper. It might seem a peculiar concept today, but if one looks at twentieth-century theory, the art world, in terms of galleries and auction houses were, en masse, somewhat blinkered and, as such, historians and academics saw Giacometti’s decorative works as unimportant, representing only trivial dalliances of an otherwise great artist. However, it was exactly these “crumbs”, in the words of French poet Louis Aragon (1897-1982), that in large part, came to define the substance of their creator.

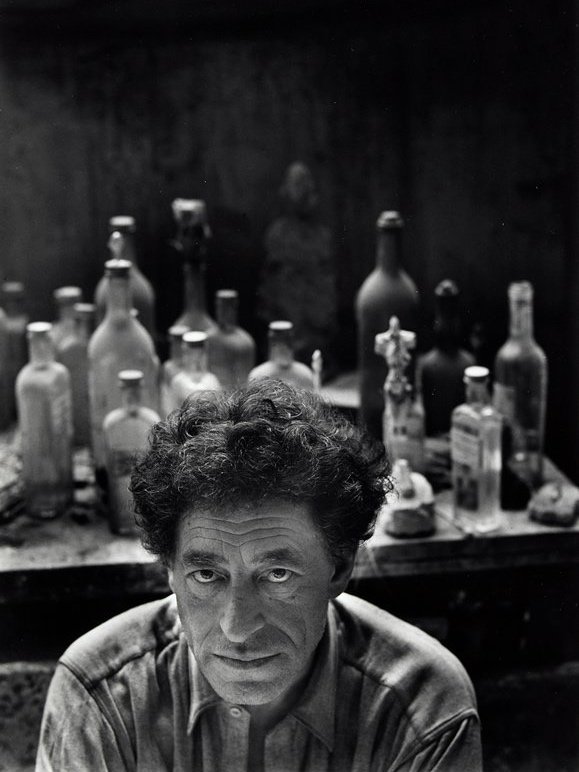

Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti in his Montparnasse studio (1954) © Arnold Newman (1918-2006) © Arnold Newman Properties/Getty Images

A conic chandelier (detail) with four small cones (c. 1954), by Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti, from the Tériade apartment, Paris © Phillips

Almost straight out of art school, the young Giacometti had become closely involved with the Paris Surrealist group and his first major commission in 1929 — the redecoration of the office of wealthy collector and banker Pierre David-Weill (1900-1975) — came to him through the intermediary of fellow surrealist, André Masson (1896-1987). Whilst it was, undoubtedly, an auspicious start, the sculptor’s inexorable commitment to the decorative arts came about as a result of his meeting maître of sophistication Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941), with whom he worked throughout the 1930s. During this period Giacometti created a number of extraordinary objects, often modelled in white plaster, a medium Frank favoured as a foil, or rather a compliment, to his often hard-edged decorative schemes, including lamps, wall sconces, chandeliers, bowls and vases. Of particular significance, as artist Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) noted, those with whom Frank collaborated “sought to submit their style towards the greater brilliance of the whole interior as the star”, yet, crucially, remained true to themselves, with pieces such as sofas, screens, and even items as seemingly mundane as planters, losing none of their creator’s personalities. It was a relationship that saw Giacometti’s work acquired by figures as diverse as English decorator Syrie Maugham (1879-1955), designer and couturier Elsa Schiaparelli (1890-1973) and infamous collectors and patrons of the arts Marie-Laure (1902-1970) and Charles de Noailles (1891-1981). Giacometti, as Jean Leymarie (1919-2006) has written, discerned “no rift between the fine and decorative arts,” thus, he “exercised the same care in creating utilitarian vases as he did in making the fantastic constructions he had on exhibit at the galleries of dealers Pierre Loeb and Pierre Colle”. It was these creations, as well as more modest commissions, including door handles and furniture hardware, that, in large part, facilitated his integration into the broader artistic and intellectual avant-garde. Giacometti first caught the eye of André Breton (1896-1966), co-founder, leader and principal theorist of the Surrealist group at an exhibition organised by Pierre Loeb (1897-1964) in 1930. His now celebrated sculpture Boule suspendue (Suspended Ball) (1930-31) caused such a furore, that a few days later Breton turned up at the young artist’s cramped Montparnasse studio and practically press-ganged him into joining the movement. Interestingly, despite the controlling, somewhat malign influence Breton exerted over the Surrealists, and unabashed hostility towards the bourgeoisie, Giacometti continued producing these utilitarian objects, seemingly unhindered, which is, perhaps, something worthy of note. By the early 1930s, Giacometti had made a return to figural representation, something met with contempt by his fellow Surrealists, yet, it was only when in 1934 he began accepting private commissions, thus aligning himself ever more closely with the haute boheme, that Breton finally excommunicated him from the group. As such, he must, presumably, have turned a blind eye to the artist’s ongoing collaboration with Frank, a testament either to Breton’s extreme admiration for the artist’s sculptural work, Giacometti’s unwavering devotion to producing “utilitarian objects”, or, perhaps, both.

An “Égyptienne” table lamp by Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) from the collection of Michelle Smith, image c/o Sotheby’s

As one of the most influential decorators in Europe, Frank proved particularly alluring for a roster of artists and architects whom one might not immediately associate with decorative arts, including Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), Christian Bérard (1902-1949), Paul Rodocanachi (1891-1958) and Emilio Terry (1890-1969); who, despite being well-known and respected figures in their own right, in the words of Cocteau, “voluntarily forgot their egos and collaborated within the ensemble without trying to steal the spotlight”. Frank was somewhat unique in that, whilst, indisputably, his contemporaries at the Union des Artistes Modernes (UAM) shared his love for materials, for Frank, it was nothing short of an obsession. Casting aside any predetermined art historical notions of hierarchy, he employed traditional methodologies in entirely new and novel ways, covering furniture in parchment and galuchat, walls in straw marquetry and upholstering in raw canvas. To a large extent, despite being thought of as minimalist, ascetic even, his aesthetic vision was characterised by the equal importance he placed on form and texture, using rough terracotta for fire surrounds and sandblasted and gauged oak for his elegant, unadorned furniture designs. In Frank’s view decoration, in terms of the mundanities of day-to-day living, came second to the visceral experience of sculpture, of volumes, such as tables, chairs and objets d’art, arranged meticulously within the confines of a carefully conceived space, and to the materials employed in their creation.

When one considers Frank’s work this way, his sparsely appointed interiors perhaps begin to make a little more sense, as does furniture layout, and placement, for example, of rock crystal and obsidian lamps, which are treated as if sculptural works of art, thus serving to further blur boundaries in terms of categorisation. Of course, not everyone appreciated his avant-garde approach, or, “renunciation aesthetic”, in the words of French novelist François Mauriac (1885-1970), who, after enlisting the young designer to redecorate his Parisian apartment, lamented its spartan, minimally furnished appearance; complaining he could no longer find his bearings, that “it is cold” and “sad”, “in the taste of the abbey cell of a monk”. Whilst Western art historians considered interior design and the decorative arts as entirely lacking in weight or gravitas, Frank’s collaborations with such celebrated artistic luminaries pushed for a wholesale rethink; it was an area in which there was considerable overlap between Frank and Giacometti’s respective ideologies. For most sculptors, plaster is, essentially, an intermediary substance, a bi-product of the lost wax process, and held in little regard — Giacometti, however, treated it as if a noble material, valuing it for its unique malleability and sense of fragility. Ernst Scheidegger (b. 1923), who documented the artist’s studio for the last two decades of his life, highlighted plaster’s natural tendency towards chiaroscuro, from the Italian chiaro, “light,” and scuro, “dark”, “as a white material, plaster is superbly well-suited to bringing a figure to life using light and shade ... the plaster casts reproduced [Giacometti’s] work in a much more differentiated and lively way than many of the bronzes could”. Indeed, in a complete reversal of the art-historical canon, Giacometti went so far as to apply a matte-white patina to some of his bronzes, such a his 1929 Surrealist-inspired Femme couchée qui rêve (“Reclining Woman who Dreams”) so as to imitate what was, traditionally, considered a supposedly base material.

Tête d’Isabel (L’Égyptienne) (1936) by Alberto Giacometti, a plaster head which bore striking similarities to the rounded profiles of archaic Egyptian statuary, image c/o Foundation Giacometti

As Frank’s popularity was on the ascendant, in March 1935 he opened a boutique on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Paris, which was, in essence, the epitome of chic — selling a refined melange of furniture and objets d’art, including anything and everything from clamshell torchères to rattan-bound scent bottles and plaster lamps, topped, perhaps unexpectedly, with apple-green, lemon-yellow and cherry-red shades. The event was captured for posterity by Hungarian photographer François Kollar (1904-1979), whose moody black and white images show a flannel-clad Frank and his business partner, decorator and cabinetmaker Adolphe Chanaux (1887-1965), surrounded by collaborators, including not only Alberto but his brother Diego (1902-1985), who, throughout his career, had assisted in the execution of his decorative works. In a letter to his gallerist Pierre Matisse (1900-1989) in 1948, Giacometti again discusses the importance he attached to this particular facet of his artistic oeuvre, whilst at the same time acknowledging his brother’s extensive help and support: “I am able to make objects only because Diego works very well and deals with all aspects of casting, etc., but objects interest me hardly any less than sculpture, and there is a point at which the two touch.”

For two of his most important commissions, the fabled Fifth Avenue apartment of American businessman and politician Nelson Rockefeller (1908-1979) and the villa of Argentine collectors Jorge and Matilde Born in San Isidro, on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, Frank used a number of decorative elements already designed by Giacometti (table lamps, floor lamps, sconces and vases), but also commissioned several new works. Of particular significance, for Rockefeller, Giacometti created a pair of luminous gilt-gold console tables, executed in plaster over a wood frame. Their elegant, undulating form exemplifies Giacometti’s unique synthesis of antiquity and modernity, capturing perfectly Rockefeller’s desired aesthetic; an evocation of the classical French style of Louis XV, which, at the same time, represented his diverse interests in modern art and objects. The otherwise heft of their construction is tempered and offset by elegant, undulating forms, and the extreme delicacy and refinement of the plaster itself. Winged arched legs rise up with graceful irregularity, serving to highlight the indelible mark of the artist’s hand and incredible mastery of the medium. For the Borns’ dining room, Giacometti again created two consoles, but this time in stone, not plaster, monumental in scale, each weighing nearly a ton, and close to three metres high, crowned with imposing bas-reliefs, decorated with a slender female figure in motion, one frontal, and the other in accentuated contrapposto. Aside from these works, Giacometti occupied something of a rarified and privileged position among Frank’s carefully assembled stable of collaborators, in the sense that no project was complete without at least one of his pieces in situ. Signing off a letter, Frank playfully cajoled him to send new designs: “PS. Everyone who comes here or to the studio swoons over your work. That’s the only thing they like. If you make more models, perhaps I’ll be able to buy myself a suit. Don’t forget me = lamps, vases, and when will there be furniture? Tables, chairs, armchairs, beds, sofas, etc.?”

“Lampe coupe aux deux figure”s (c. 1950) (detail), by Alberto Giacometti, where two wonderfully elongated figures flanking a central coupe, bear a striking resemblance to the artist’s austere “Walking Man” (1947)

“Vase modèle dit aigle” (c. 1934) by Alberto Giacometti, a work of supreme elegance and refinement, executed at a key moment in the artist’s career, image c/o Sotheby’s

When creating such decorative works, Giacometti ignored modernist functionalism, instead taking the view that separate elements formed part of an overall artistic oeuvre, as reflected in his writings on Chaldean art, where he notes that “even if a sculpture is broken in four, then those four elements are each vital sculptures in their own right”. There was often such an overlap apropos Giacometti’s relentless experimentation and artistic evolution that it’s almost impossible to say with any degree of certainty whether it was the decorative arts that influenced his sculptural practice or vice versa; this is immediately apparent in his 1936 Tête d’Isabel (L’Égyptienne) (Head of Isabel (The Egyptian)), a plaster head which bears noticeable similarity to the rounded profiles of archaic Egyptian statuary and featured in a number of Frank’s interior designs. Of course, numerous parallels can be drawn between Giacometti’s furniture and sculptures, as evident in Lampe coupe aux deux figures (c. 1950), where two wonderfully elongated figures flanking a central coupe, bear a striking resemblance to the artist’s austere Walking Man (1947), created in the aftermath of the Second World War and seen by many as a monument to the unyielding spirit of Auschwitz victims. Likewise, one can draw parallels between the angular surfaces of Vase modèle à facettes (c.1934) and the irregular planes of his only abstract sculpture Le Cube (1934-35) (“The Cube”), which references the mysterious polyhedron in Melencolia I (1514), an iconic engraving by Renaissance painter, draftsman, and printmaker Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528). This visual synthesis had, in many ways, culminated with the artist’s La table surréaliste (1933), in which Giacometti seems to be encouraging a synthesis of the arts by creating a composite sculpture made up of an assortment of abstract and figurative sculptures arranged on a table — a visual union of both of these leading elements of his oeuvre at the time. Recalling such commissions, Giacometti once said: “I came to realize that I made a vase in exactly the same way as I did a sculpture and that there was no difference between what I termed a sculpture and an object, a vase! I had previously thought that a sculpture was different from an object. This all came as a shock. I had bypassed the mysterious, my work was not a true creation, it was no different from the way a cabinet maker makes a table.”

Giacometti developed an aesthetic that was unusual, in the sense that it was grounded in archaic historicism, yet also fantastical, a predilection shared by contemporaries such as decorators Armand-Albert Rateau (188-1932) and Marc du Plantier (1901-1975). Inspired by the Cubism of Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), from the mid-1920s Giacometti had become increasingly interested in non-European arts, in particular, traditional African and Oceanic sculpture, whose use of abstraction over naturalistic representation appealed to a Parisian avant-garde breaking away from traditional “Western” painting styles. Giacometti’s Femme cuillière (1927), which takes its purity and geometrised elementary forms from Brancusi, was most probably inspired by a ceremonial spoon from the Dan people of the Ivory Coast and Liberia, transposing a ritual object into sculpture. In the same way, Giacometti found objects in the arts of the past that he could use to compose his decorative works. His Égyptienne lamp, for example, designed in 1934 for Frank, is, in essence, a stylistic homage to the highly complex alabaster oil lamps discovered in 1922 in the tomb of Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun. The sculptor simplified and pared back the oil lamp’s original form, removing every trace of its side armatures and incised floral details, resulting in a profoundly modern and abstract work: “For me, the most beautiful statue is neither Greek nor Roman and certainly not from the Renaissance — it is Egyptian,” Giacometti wrote in 1920. “The Egyptian sculptures have an excellence, an evenness of line and shape, a perfect technique that has never been mastered since.” Similarly, his Grande Feuille (1933-1934) (“Big Leaf”) floor lamp borrows details from a Polynesian offering-bearer that Giacometti may have seen at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. However, if one looks at the entirety of his production, such explicit references are rare, as more often than not, the artist preferred to allude to works from the past rather than quote them literally. This is perfectly illustrated by Vase modèle dit aigle (c. 1934), which was executed at a key moment in Giacometti’s career.

Immersed in the production of his decorative works, Giacometti had become increasingly frustrated with the Surrealist’s more eccentric escapades and began to turn his back on this particular thread of modernism in favour of a return to figural representation. Appearing at once like an ancient vessel, while at the same time, remaining entirely contemporary, the Aigle vase is a work of supreme elegance and refinement. “The pieces he created are like objects he exhumed from imaginary civilisations,” explains Thierry Pautot, head of archives and research at Foundation Giacometti. “Despite the apparent symmetry, the surfaces are in fact uneven, scratched, even damaged.” The artist’s shift away from surrealism is apparent in the recognisable, albeit stylised and simplified, head of an eagle, perched upon the rim of the vase. When viewed from the side, the top of the vessel appears as if the expansively outstretched wings of a bird in flight; a recurring motif in Giacometti’s work, and likewise, that of Diego. Testament to the importance of this form in both the eyes of the artist and his peers, a black version of the Aigle vase can be seen positioned prominently behind Frank at his shop opening in 1935.

As Giacometti reminisced in a 1962 interview with French art critic André Parinaud, “For my livelihood, I accepted to make anonymous utilitarian objects for a decorator at that time, Jean-Michel Frank ... it was mostly not well seen. It was considered a kind of decline. I nevertheless tried to make the best possible vases, for example, and I realized I was developing a vase exactly as I would a sculpture and that there was no difference between what I called a sculpture and what was an object, a vase!” Giacometti and Frank developed a genuine friendship, and together, they created an original aesthetic based on extreme simplicity of forms and limited colours, while regularly finding inspiration in the past. While more than half of Giacometti’s decorative work was lighting (floor lamps, lamps, sconces, chandeliers), plus a smattering of bowls and vases, he also tried his hand at making items of furniture, including mantelpieces, firedogs, door knobs, mirrors, pedestal tables and other decorative accessories. Aside from Frank, the artist accepted a small number of private commissions, making jewellery and buttons for Schiaparelli and creating a unique plaster wall decoration (1934, now lost) for French writer Lise Deharme (1898-1980). The onset of the Second World War, and Frank’s tragic and untimely suicide halted production until Giacometti returned to Paris in September 1945 and resumed work with Diego, whom he entrusted with managing editions of several models he had created for Frank.

Up to the early 1950s, the artist produced a very small number of new works, albeit only for very close friends and patrons, such as art critic and publisher Tériade (1897-1983) and his gallerist Aimé Maeght (1906-1981). In addition to the three plaster ceiling lights, Tériade owned bowls, floor lamps and a Flambeau table lamp which Giacometti included, rather prominently, in the foreground of a portrait of him from circa 1939. For French publisher Louis Broder, Giacometti created a particularly extraordinary work (1949-1952), combining in a single chandelier the emblematic figure of the walking man with that of a standing woman raising her arms, as in the first version of The Cage (1950). Such pieces are comparatively rare and much sought after by collectors, and as such, a unique chandelier commissioned by one of the most important cultural figures of the mid-twentieth-century, Peter Watson (1908-1956), sold this week at Christie’s London for just short of £3m. Despite the dwindling number of “utilitarian objects” produced by Giacometti towards the end of his career, his passion never wavered, and in 1952 he wrote to Pierre Matisse, who was at that time the exclusive distributor of his works in the American market, “I have modelled a bowl that is by the far the best thing I’ve done in this field.” Given their inexorable relationship, the enduring and lasting appeal of Giacometti’s decorative works can perhaps best be summed up in the words of his friend and collaborator Jean-Michel Frank: “A single object can furnish a room, so long as it is beautiful.”