Nothing Posh

In the face of adversity

“'Every Sunday I would walk across the railroad tracks into the affluent part of Durham and buy Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, and go back to my grandmother’s house, read my magazines. I was allowed to retreat from the bullying and the sexual abuse into a beautiful world.” — André Leon Talley

At a recent Supper Club thrown by editor and journalist Gianluca Longo, a well-known designer and interiors columnist for US Vogue was discussing a magazine he’s soon to launch, and in reference to what the focus would be he stated, simply: “Nothing posh.” Posh is of course a somewhat loaded term, referring pejoratively to the manners and attitudes of what has been traditionally termed the “upper class”, a now largely redundant anachronism referring to those with the highest social rank. There’s a widely held misconception, etymologically speaking, that “posh” stands for “port out, starboard home”. As the story goes, on ocean voyages between Britain and India, the most desirable cabins — i.e. those that didn’t catch the heat of the midday sun — were port side out and starboard home, with tickets, supposedly, stamped with the acronym POSH; a charming, if somewhat hackneyed tale, that has absolutely no evidential basis. Instead, posh entered the English language early in the 1900s, in a wholly un-nautical context, to mean “smart” and “stylish”. Since then it’s become inextricably bound up in ideas of elitism and snobbery, considered by many as the very antithesis of “cool”, and looked down on derogatively by those who consider its often unwitting proponents as antediluvian and irrelevant in terms of the cultural zeitgeist. The perception of “poshness” as a quality is associated not only with appearance but the way in which people sound, and apparently, at least according to FT writer Janan Ganesh, who recently wrote about “voice privilege”, it offers economic advantages that go further than a mere trust fund and flat on the Chelsea borders. In recent years as part of an ever more concerted attempt at levelling the playing field, as it were, apropos social equality, there has been a focus on privilege beyond the material, i.e. those qualities in life that offer certain individuals an unfair advantage over others, that aren’t merely a consequence of inherited net worth. One such example is beauty, the social and economic returns of which are such that some have gone so far as to suggest it should be offset through fiscal redistribution, in the form of what would, essentially, be a prettiness tax. Similarly, as to public perception, a great deal of clout is accorded to an accent that has, as a matter of course, been termed “upper-crust English”, which seemingly lends a veneer of erudite sophistication to those with the plummy vowels and clipped consonants associated with an expensive private education. Ergo, Ganesh hypothesises, it goes some way to explaining why anyone would want to pay Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (b. 1964) a reported £2.5m as an advance for speeches, which, I’m sure anyone would agree, seems awfully steep for twenty minutes of “Caecilius est in Peppa Pig World”. Stephen Fry is another for whom an accident of birth, i.e. good timbre and pitch, as well as an innate aptitude for eloquence, redolent of a more lighthearted, Wodehousian time, has been used to monetary advantage. The educational charity Sutton Trust goes as far as to argue accent is in fact the primary signal of socioeconomic status, with its recently published report indicating nearly half of all adults consulted (46%) had been singled out or mocked socially for their regional dialects, with Mancunian, Scouse and Brummie considered amongst the least “prestigious” or desirable. Of course, beyond the auditory, without even opening one’s mouth research shows most of us make a “first impression” of someone within the first seven seconds of meeting them; with a series of experiments by Princeton psychologists Janine Willis and Alexander Todorov suggesting all it takes is a tenth of a second to form an impression of a stranger, and so clearly every element of our appearance, as regards the choices we make, from our clothes to our hairstyle act a social signifier, conveying meaning to others, whether we intended it to or not.

Former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, whose fear of obscurity and passion for beauty saw her transformation from a society career girl into a twentieth-century icon, tastemaker and doyenne of high fashion

The Maximalist home of fashion editor Diana Vreeland, designed by the “dean of interior decorators” Billy Baldwin, and dubbed the “Garden of Hell”, photograph by Horst P. Horst, Vogue, 1979

Staying within the realms of the aesthetic, as opposed to auricular, Vogue has over the decades frequently been referred to as “the Bible of fashion”, and for many years, before social media, it dictated trends, opening up a world of fantasy and make-believe to those readers who had little or no hope of experiencing it first-hand. As such, given its egalitarian outlook, helping, in essence, to democratise and demystify the world of fashion, which, for the most part, in terms of price point, is still inaccessible to the majority of the global populous, it might be interesting to look at three figures inextricably linked to the magazine’s DNA so as to examine the idea of “poshness”, and whether or not it’s widely perceived understanding is dependant on class or privilege. Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour (b. 1949) has, in effect, entered the cultural consciousness as the gatekeeper of fashion, having presided over the magazine for over three decades, immortalised in the allegedly Wintour-inspired character of Miranda Priestly (played by Meryl Streep (b. 1949)) in the 2006 comedy rom-com The Devil Wears Prada; however, the woman who made the magazine a cultural litmus test was, in fact, inimitable style icon and legendary fashion editor Diana Vreeland (1903-1989), the twentieth centuries most formidable arbiter elegantiarum — whose fear of obscurity and wanton passion for beauty saw her transformation from a society career girl into a twentieth-century icon, tastemaker and doyenne of high fashion. Vreeland had an almost preternatural talent for identifying the very best in any given field, endowing them with a very special sense of being “chosen”, thereby moulding and shaping everyone from workmen to “skivvies” — her office assistants — into giving more than they ever knew possible. All of her successful protégés, from Grace Mirabella (1929-2021) to André Leon Talley (1948-2022) and Polly Mellen (b. 1924), saw it almost as if they had been touched by the divine. “Once she decided she saw something in me,” Talley enthused. “I could do no wrong.” Mirabella agrees: “She hooked you. We all had the feeling that we’d die for her. From the moment she wanted you, you were as loyal as a Labrador.” It was Vreeland’s unbridled imagination, which was in perfect harmony with the hedonism of the 1960s and 70s — a “cultural revolution”, that gave rise to rock music, the pill, Warhol’s factory, as well as the British wave, including the Beatles and Twiggy — that set her apart from the pack and helped her turn Vogue into a cultural klaxon.

Despite her upbringing as an Upper Eastside debutante, Vreeland was so ambivalent towards counterculture excesses that American fashion illustrator Joe Eula (1925-2004) recalled an instance when, at a meeting in her scarlet-walled, leopard-carpeted office, a vial of cocaine fell out of his jacket; without so much as a raised eyebrow, Vreeland’s only wry comment was to suggest he should probably wear pockets that button. Enamoured by the avant-garde, no ideas were too outlandish and no expenditure too excessive, but, as photographer David Bailey (b. 1938) recalled, she had a very specific creative vision: “Once, I spent the whole day with [model] Penelope Tree to do two pictures. Diana told me, ‘They’re wonderful, but we can’t use them.’ I asked her why. ‘Look at the lips,’ she said. ‘There’s no languor in the lips!’” Whilst, undoubtedly, she could be a nightmare to work with, Vreeland had a particular savvy for predicting the spiritus mundi that set her apart from the pack — she featured the first portrait of Mick Jagger (b. 1943), helped bring photographer Richard Avedon’s (1923-2004) work to the covers of Vogue and made Verushka (b. 1939) and Lauren Hutton (b. 1943) the first supermodels. Vreeland was a fashion genius, but despite, in the words of art critic John Richardson, her “extraordinary perspicacity about human nature”, her excessive spending became increasingly problematic and as the 1960s go-go economy capitulated to the recession austerity of the 70s, Condé Nast fired her in favour of Mirabella, who, according to legendary editorial director Alexander Lieberman (1912-1999) “addressed the needs, the looks, of the real, modern American woman”. Vreeland was an idealist, who established a reputation as the high priestess of fashion, she was described by some as a kind of seeress, a philosopher whose raison d’être was style, chasing fantasies and going beyond material boundaries, all in the pursuit of beauty. She was also, of course, from privilege, and as a young woman she threw herself into society with a vengeance (after all, her career got off the ground when Harper’s Bazaar editor Carmel Snow (1887-1961) spotted a flower-festooned Vreeland dancing on the roof of the St Regis hotel, wearing head to toe Chanel, and offered her a job as a columnist on the spot), and yet, at the same time, as with Marie-Laure de Noailles (1902-1970) and Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979), she was a champion of the avant-garde, embracing wholeheartedly the “Youthquake” (one of her favourite neologisms) of the 1960s that pulled down social barriers and overthrew elitism, fundamentally altering the fashion landscape, in essence, by taking dominance away from “posh” French couture houses.

The inimitable fashion icon André Leon Talley, standing beside one-time friend and confident, couturier Karl Lagerfeld, at the Élysée Palace, photograph by Robert Fairer, Vogue, June 2010

The home of editor-in-chief of Vogue Italia Franca Sozzani, where above the fireplace, rests a portrait of Sozzani by Julian Schnabel, photograph by Matthieu Salvaing for AD Magazine

Larger-than-life American writer, journalist and former Vogue editor André Leon Talley got his start in fashion with an apprenticeship to Vreeland at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, at which, following her unceremonious dismissal, she found her calling, breathing new life into what had formerly been an obscure offshoot, visited largely by fashion designers and scholars. In stark contrast to Vreeland’s privileged upbringing, her protégé was from considerably humbler beginnings. Born in Washington, D.C., Talley was raised in Durham, North Carolina by his grandmother, who worked as a maid on the Duke University campus during the racist Jim Crow era. As the story goes, upon hearing Julia Child (1912-2004) say “Bon appetit!” on her TV cooking show, Talley became so enamoured by all things French, that he went on from North Carolina Central University, on a scholarship to Brown, where he wrote a master’s thesis about black women in nineteenth-century French art and literature. “I went to school and to church and I did what I was told and I didn’t talk much,” he told Vogue. “But I knew life was bigger than that. I wanted to meet Diana Vreeland and Andy Warhol and Naomi Sims and Pat Cleveland and Edie Sedgwick and Loulou de la Falaise. And I did. And I never looked back.” Talley was soigné, to use one of his favourite words, and had éclat, to use another, and from the MET, he went on to work at Andy Warhol’s (1928-1987) much-mythologised Interview magazine, followed by Women’s Wear Daily and the New York Times, before taking the Fashion News Director job at Vogue in 1983, quickly rising through the ranks to claim the carefully gate-kept title of Creative Director and Editor-at-Large; the first black man to hold the position, and oftentimes the only black person in the front row at fashion shows. In the 2018 biopic The Gospel According to André, he opined, “you don’t get up and say, ‘look, I’m Black and I’m proud,’ you just do it and it impacts the culture”.

That said, despite sending Wintour handwritten notes about his experiences with race, he avoided the subject publicly, concentrating instead on his unique personal status in the fashion world, through which he was able to usher in a more inclusive era, championing black models like Naomi Campbell (b. 1970) and designers like Stephen Burrows (b. 1943). “To my twelve-year-old self, raised in the segregated South, the idea of a black man playing any kind of role in this world seemed an impossibility,” he recalled in his 2020 memoir, The Chiffon Trenches. It was only after being unceremoniously ousted from his role hoisting the Met Gala red carpet live stream, to be replaced by a 24-year-old up-and-coming YouTube star, he said, for being “too old, too overweight, and too uncool”, that he scathingly described Wintour as “a colonial broad”, steeped in “white privilege”, on whose watch Condé Nast remained undiversified into the twenty-first century. Despite his professional success, Talley felt, in large part, as described by Guardian columnist Veronica Horwell, that he’d been “exploited as an ‘exotic’, and sometimes as an ambassador for a black milieu; always the first to be bumped from a guest list”. With his gravitas, fluent French, and signature uniform of oversized furs and brightly coloured capes and kaftans, Talley cut a figure in any room he entered. A Goliath of intellect, with an encyclopaedic knowledge of couture, he was a true trailblazer for forty-plus years in an industry that had very little diversity in its upper echelons, becoming a confidant of Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008), Paloma Picasso (b. 1949) and Diane von Furstenberg (b. 1946), amongst others. Despite his many disappointments, Talley never lost his love of fashion, and from the early days, when couturier Karl Lagerfeld (1933-2019) gave him cast-off crêpe de Chine shirts from Hilditch & Key, he developed a penchant for the finer things in life, including Savile Row suits and Manolo Blahnik shoes, both of which would, presumably, fall under the criterion of “posh”, yet, there could be no doubt, that they were chosen as an expression of personal taste and savoir-faire. As American fashion designer Tom Ford (b. 1961) so eloquently expressed in a 2018 documentary about Talley, “[he] is one of the last of those great editors who knows what they are looking at, knows what they are seeing, and knows where it came from.”

Hôtel d’Orrouer, the home of aristocratic couturier Hubert de Givenchy, where in the petit salon Picasso’s “Faun With a Spear” (1947) hangs over an antique console © Christie’s images limited, François Halard

Franca Sozzani (1950-2016), like Vreeland, was another groundbreaking editor, almost ousted by Conde Nast early on in her editorship for her unwavering commitment to the avant-garde, which, initially at least, resulted in an exodus of advertisers. Sozzani was from a generation of Italian women, such as Miuccia Prada (b. 1949), who, in essence, ended up in fashion almost by default. Born in Mantua, northern Italy, her father, an industrial engineer, and “classic Italian patriarch”, didn’t approve of his daughter’s early ambitions to study physics, “my father thought that wasn’t right for a woman”, and so instead, she studied philosophy at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore. Sozzanni married soon after graduation, although she knew, as she later admitted, that it was doomed from the get-go, and within three months (divorce was not an option in Italy at the time), unusually, she managed to get an annulment from the Catholic Church — something even actress Ingrid Bergman (1915-1982) had difficulty pulling off. Her sister, then working in fashion, saw an ad in Corriere della Sera for an assistant at Vogue Bambini and applied on Sozzani’s behalf. “I thought it would be something to do for a few years. I never really took it seriously at all,” she told the Financial Times. Then things suddenly started to click, as if, perhaps, it were finally time to prove something, quite possibly, even, to her father. “It was ‘77, ‘78; people were very politically oriented. I was coming to work dressed in Saint Laurent, and everyone else was a hippie with long hair, and they always said, ‘Oh, she’s too bourgeois’, and at a certain moment, I cut my hair and only wore jeans and I started a new approach. I said, ‘I am bourgeois, but I can do this, even me.’ So I started to take it very seriously, and I was working hard.” By 1980, aged 29, Sozzani landed her first editorship of the influential Italian fashion magazine Lei, with Per Lui, its equally remarkable male counterpart, following two years later. When photographer Oliviero Toscani (b. 1942), her linchpin, moved on from the magazines, unperturbed, she saw it as an opportunity to assemble, and nurture, an extraordinary stable of emerging photographers including Peter Lindbergh (1944-2019), Paolo Roversi (b. 1947), Herb Ritts (1952-2002), Steven Meisel (b. 1954) and Max Vadukul (b. 1961); all of whom were drawn in by the unprecedented level of creative and editorial freedom they were afforded, which, over the years, they used and abused to spectacular, often outrageous effect.

From the beginning, Sozzani sought an unusual narrative element, and what stands out about her early editorial efforts is how fascinated she was by alternatives, in terms of moving away from mainstream trends, not only with respect to photographers but also models and subject matter, an approach which would become increasingly polemic, designed to provoke and intrigue a readership that, she thought, had grown weary of monotonous, repetitive fashion shoots. Eight years later she landed at Vogue, and in 1998 Sozzani was appointed Editor-in-Chief (the same month Anna Wintour began as Editor-in-Chief of US Vogue). “Why would anyone buy Italian Vogue?” she once queried, “They wouldn’t—only Italians read Italian.” A recurrent theme throughout her career, Sozzani knew the only way to capture the public’s attention was through shock tactics; she quickly grasped the power of the image as something capable of transcending the magazine’s national reach, and as such, Sozzani immediately shook up the formulaic title with dynamic covers and content, creating a magazine that, in her words, would be “extravagant, experimental, innovative”, and became a platform for celebrating the power of the image and of photography.

Sozzani became increasingly frustrated by the fact that those who professed an interest in fashion and design had no real understanding of its history (a current trend in the world of interiors), and that articles in mainstream media were entirely lacking the depth of context. She was fearless in her willingness to tackle provocative, often controversial issues through photo shoots, and as such, with the release of each and every issue, she pushed the cultural needle, creating work that challenged fashion’s status quo. “Before fashion, I love images. I love to find a new way to make an interpretation of fashion. I use the frames to send messages, like frames of an old movie,” she told the Wall Street Journal. “Besides the culture of our past, Italy has cinema: Fellini, Visconti, Antonioni. You want it to be aesthetic but with meaning. Otherwise, you get tired of even the most beautiful things. It’s not enough if there’s not a concept inside.” In essence, Sozzani helped reimagine the very medium of the fashion magazine as something approaching a cultural lightning rod, tackling social, political and environmental issues, often even preempting the zeitgeist; subjects included a prescient takedown of the contemporary obsession with plastic surgery (“Makeover Madness”, July 2005, photographed by Steven Meisel, and starring Linda Evangelista (b. 1965), Julia Stegner (b. 1984), and Missy Rayder (b. 1978), amongst others), the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico (“Water & Oil”, Steven Meisel, July 2010, a slice of gothic Sturm und Drang with images of model Kristen McMenamy (b. 1964), wearing a fur coat and covered in oil slick — which drew criticism for its apparent glamourisation of environmental tragedy), and violence against women (“Horror Movie”, Steven Meisel, April 2014). “Fashion isn’t really about clothes,” Sozzani opined, “it’s about life.” In 2008, she produced the “Black Issue”, its editorial pages, again, shot entirely by Meisel, featuring exclusively black models, with every article dealing with some aspect of black culture.

Despite ire from certain detractors, it sold out in both the US and UK within 72 hours, forcing Condé Nast to reprint 60,000 extra copies and becoming an instant collector’s item. “Franca doesn’t realize what she’s done for people of colour,” her friend Naomi Campbell told The New York Times, “It reminds me of Yves using all the black models,” referring to Saint Laurent, who, like Gianni Versace (1946-1997), and a handful of other designers, routinely cast minorities. While the issue reignited a conversation about the need for more racial diversity, its impact was, sadly, shortlived, lasting for all of a fashion minute, and even now, against the backdrop of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, when it comes to the hierarchical power structure of established fashion brands, black representation is still incredibly small. Sozzani’s search for something “more than just a beautiful woman in a beautiful dress” saw her taking an active role in social issues beyond the pages of her magazines; as well as promoting emerging designers through her Who Is on Next? initiative, she was creative director of Convivio, the AIDS initiative launched by Gianni Versace in 1992, and also founded Child Priority with Condé Nast International CEO Jonathan Newhouse, to provide work opportunities for underprivileged children. “The problem with clothes nowadays, is the same problem with magazines – they’re all the same,” Sozzani told Forbes. “Nobody is willing to be courageous it seems, and head in their own direction. Not everybody may like what I do with Vogue Italia of course, but who cares?”

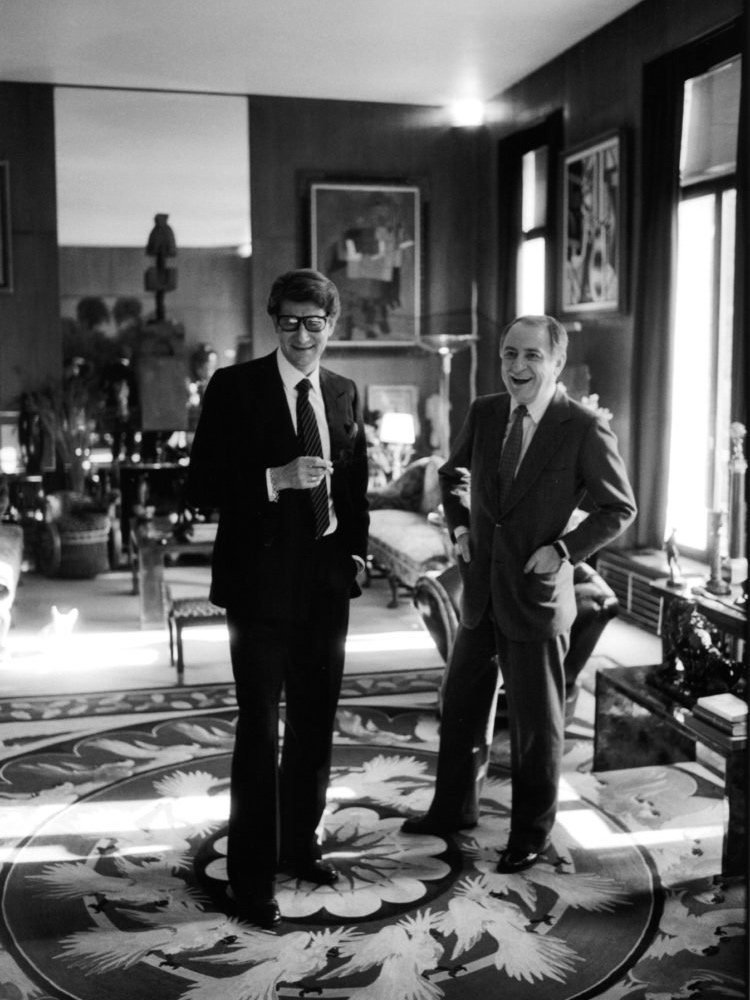

French couturier Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008) and his partner Pierre Bergé (1930-2017) in the now iconic Art Deco salon of their rue de Babylone apartment

Essentially, what these three figures, straddling the socioeconomic spectrum demonstrate, is that despite obvious barriers to advancement such as gender, race and sexuality, its entirely reductive to suggest those things traditionally considered “posh”, including, non-exhaustively, all aspects of the arts, such as furniture, painting and sculpture, as well as fashion, opera, classical music etc. are of interest and ergo, suitable, only for “upper classes”. This is especially so in the realm of interiors, as works by designers and artisans are, inherently, of a price point unaffordable to the majority of consumers; even those twentieth-century modernists such as Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) and Jean Prouvé (1901-1984), who expressed a genuine egalitarian desire to produce well-designed, affordable furniture for the masses, essentially failed, as the end cost, even with advances in industrial production methods, was still, inherently, extremely expensive, and therefore, a luxury. On that basis, especially given original works are sold for astronomical prices by high-end galleries and auction houses (earlier this month an “Ours Polaire” sofa and armchair set achieved a record $3.5m at Christie’s New York), should such works be given short shrift as too “posh”, in terms of magazine coverage, for the man on the Clapham omnibus? The same can be said of art, with “blue chip” works by Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Warhol and Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) et al fetching eye-watering prices. Even if one looks at the lives of such artists, they were somewhat removed from those of mere mortals. Picasso, perhaps the world’s best-known artist, is a prime example, stating as his mantra, “I’d like to live as a poor man with lots of money”, which presumably led to his acquiring the eighteen-room mansion La Californie, overlooking the bay of Cannes, where he roamed around its palatial, sun-drenched rooms in his signature Breton stripe t-shirts and espadrilles (when he wasn’t wearing bespoke tailoring from Anderson & Sheppard of Savile Row). Societally speaking, the term “posh” is increasingly problematic, as those children who gravitate towards the arts, interiors, fashion etc., but are not from backgrounds traditionally associated with such interests (eleven-year-old coal-miners son Billy Elliot being a case in point, a story inspired by Sir Thomas Allen, who faced similar struggles in his pursuit of becoming an opera singer in the 1960s) have it thrown back at them as if they’re somehow betraying their roots, thereby preventing social advancement and equality, placing unnecessary barriers in the way of a levelling the playing field.

Reverse snobbery can be just as damaging as elitism, as it discriminates against those who don’t necessarily fit into a prescribed mould, who might have different interests than those of their peers and who simply want to be themselves, without fear of judgment or ridicule. Pierre Bergé (1930-2017), the son of a tax official and a teacher, went on to become one of the greatest aesthetes in history, with even Saint Laurent describing him as the driving force behind their collection, enthusing that in the future, in matters of style and taste, we will speak of le goût Bergé, just as one refers to le goût Givenchy or le goût Rothschild. “I don’t know where my taste comes from … it’s a mystery,” Bergé mused, “My family never had the least interest in the arts or knew anything about them, and surrounded themselves with hideous furniture, paintings and objects.” Equally, it should be remembered, that even though there are those fortunate enough to have been blessed either with the confidence or perspicacity, at risk of sounding saccharine, to follow their dreams, the traditional “upper” or ruling class are still keen to keep a tight grip on power, and are not averse to making things difficult for those trying to make a career for themselves, who might not have been taught the intricacies of social nuance that a privileged upbringing imparts. Figures like Bergé, Talley, Vreeland and Sozzani operated outwith outmoded, pre-conceived societal norms regarding what’s acceptable for X, Y, or Z background, which left them free to be themselves, which is, in essence, what made them so unique, and in turn, so influential in their respective careers. “What I think very much brings us together is firmness of vision,” filmmaker and photographer Francesco Carrozzini (b. 1982) said of his mother, Franca Sozzani, “and we’re both careless about what people think and say, and that’s how we move through this very difficult world, I guess.” The term “posh” should be relegated to this history books, as it is, in effect, either a redundant term of inverse snobbery, used as a means of putting “class traitors” in their place or as some peculiar, almost deferential term of art used as shorthand to describe those things, be it furniture, clothing, paintings, sculpture, even hairstyles, that are apparently considered outwith the reach of the average Joe; a throwback to an era when, by and large, those who could afford luxury goods were from intergenerational wealth. Fortunately, times are changing, and one would hope future generations will be able to embrace any aspect of their personality without fear of contempt or derision.