Designing for Collectors

Gesamtkunstwerk Interiors

“I’m too old now to begin a new collection. It’s a shame, because if my days weren’t numbered, I know I’d start a new one. You could ask how can I be so sure; I would answer, although I’m not entirely certain, that it’s deep down inside me … It’s art that has the strongest impact on me, that remains essential, that I know the most about, and that makes me the happiest. Sometimes I regret never having taken history of art courses. Would that have changed anything? I wouldn’t have liked paintings any more or less. I detest didactic learning and anything connected with it. To love you need to forget everything which is what I’ve never stopped doing.” — Pierre Bergé, in a letter to Yves Saint Laurent, 2009

When it comes to interiors, clients can, often, be incredibly difficult, especially as regards to budget; and for decorators that wish to work with skilled artisans and craftsmen such as Maison Lesage, Paris’ oldest embroidery atelier, Féau Boiseries, Jouffre or Atelier Saint-Jacques, it takes more than snaring the 0.01%. While a good many of the world’s “super-rich” might think nothing of splashing out on the latest Ferrari or limited edition Patek Philippe watch, they wouldn’t necessarily appreciate, or for that matter care, about the difference between bronze finishes or the quality of boiserie (in respect of its being hand-carved and painted or machine routed and sprayed) and seldom see such an investment as in any way justifiable; an issue further compounded when “added value” associated with the interior design process is measured not in terms of aesthetics, but as a deduction in an overall cost balancing exercise, to be set off against a properties potential resale value. Those that not only understand such esoteric nuances but have the means to commission an all-encompassing gesamtkunstwerk, tend to occupy something of a rarefied world, working with only a handful of decorators such as Jacques Grange (b. 1944), Atelier AM, Stephen Sills (b. 1951), Jacques Garcia (b. 1947) and François-Joseph Graf et al, where there’s a mutual simpatico between designer and client, both parties appreciative of the cold hard truth that very best in quality has a corresponding, often astronomical price tag. At the very pinnacle of such brazen spending, a well-known architecte d’intérieur, who describes his work as having an “haute couture” aesthetic, recently enlisted the services of a storied French atelier to create an extraordinary set of hand-embroidered curtains, along with a matching headboard, for the primary suite of a Parisian apartment that came in at a cool €2m — the sort of commission that would see a good many oligarchs reach for the smelling salts. Retail pioneer Sir Terence Conran (1931-2020), who broke down class barriers by making fashionable furniture accessible to the masses once said, “furniture and food are ways that people define their attitude toward life. They’ll buy better stuff if it’s offered to them”. That might be true apropos the designer’s own eponymously named emporium (which somewhat inexplicably, recently moved from its iconic Michelin House headquarters), which, like Heal’s, sells well-designed furniture to an aspirational middle class; but when it comes to the crème de la crème of twentieth-century design, furniture by the likes of Pierre Chareau (1883-1950) and Eyre de Lanux (1884-1996), or, to boot, that by the very pinnacle of contemporary designers and makers, those willing to cough up, are, sadly, few and far between, with many failing to understand the inherent cost involved in producing such works.

French couturier Jeanne Lanvin’s (1867-1946) extraordinary Paris bathroom designed by Neo-classically inclined Art Deco maestro Armand-Albert Rateau’s (1882-1938)

Panelling in gilt oak with a relief pattern of waves, created by Féau Boiseries for the bedroom of a private villa in Monaco

Similarly in terms of hardware, more often than not, as projects fall victim to value engineering, bespoke handles, taps and switches find themselves jettisoned in favour of cheaper, off-the-shelf alternatives, as, quite frankly, whilst there are always exceptions, unlike an investment, say, in art or antiques, returns are, quite frankly, far less likely; whilst Armand-Albert Rateau’s (1882-1938) discerning patrons, those such as Cole Porter (1891-1964) and French couturier Jeanne Lanvin (1867-1946), will have splashed a pretty penny — no pun intended — on his fantastical neo-classical bronze bathroom fittings, it was as a result of their unnerving admiration and trust in the designer’s unique vision, without recourse to their client rep commissioning a detailed cost-benefit analysis. To take the fashion analogy one step further, there are a good many fledgling high spenders, especially those whose trajectory into the glittering stratosphere of the super rich has been a sudden, even overnight occurrence, who seek solace in making choices that are, for all intents and purposes, dictated to them by ad agencies. To turn once again to an oft-quoted anthropological survey of the liberal metropolitan elite, BBC sitcom Absolutely Fabulous, PR expert Edina “Eddy” Monsoon is, essentially, a fashion victim, wearing whatever’s “in”, or “on trend”, even going so far as to say such designer labels help her dissociate from her own body image, with which, she is eternally dissatisfied: “Dolce & Gabbana fat thighs, not mine!” In a similar vein, buying furniture by the likes of Fendi Casa, Lora Piana Interiors, or Armani Home, takes issues of taste away from the individual and places it on big brands. Of course, it’s not only amateurs, there are myriad well-known architects and designers doing, in essence, the exact same thing, with numerous professionally decorated contemporary interiors featuring tables and lamps in the “style of” brothers Alberto (1901-1966) and Diego Giacometti (1902-1985), sofas and armchairs in the “style of” Royère (1902-1981) or Vladimir Kagan (1927-2016) and dining tables in the “style of” Perriand (1903-1999), not as a means of historical homage, but so as to give their work gravitas. In effect, such appropriation lends a veneer of “good taste” associated with the homes of collectors, those such as Bunny Mellon (1910-2014) and Pauline de Rothschild (1908-1976) and more recently Emmanuel de Bayser, whose superlative approach has entered the cultural consciousness through countless shoots and editorials, cementing them as arbiters of sophistication.

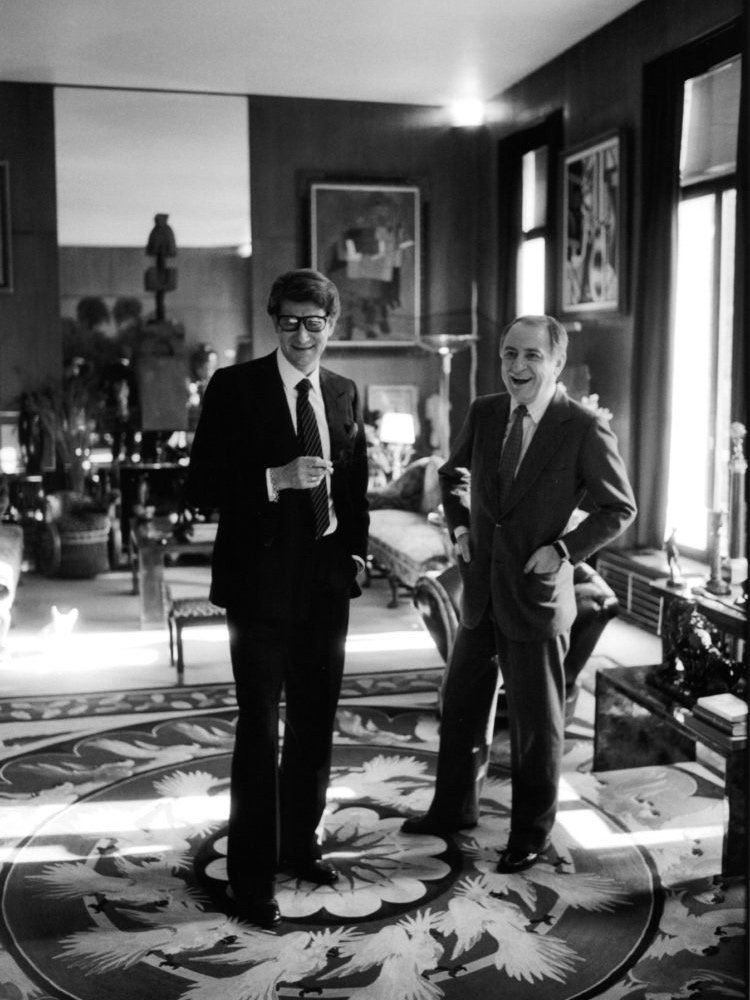

French couturier Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008) and his partner Pierre Bergé (1930-2017) in the now iconic Art Deco salon of their rue de Babylone apartment

An art-filled Chicago penthouse designed by Alexandra and Michael Misczynski, the husband-and-wife team behind Atelier AM, photograph by François Halard

Perhaps most influential are the numerous homes of French couturier Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008) and his partner Pierre Bergé (1930-2017), two of the greatest tastemakers of our time — including, non-exhaustively, rue Bonaparte in Paris, Mas Theo in St Rémy de Provence, the Villa Leon l’African and later the Villa Mabrouka, both in Tangier — all of which were distinctive and idiosyncratic expressions of the couple’s unique approach and intense passion for collecting. The colossal success of the YSL fashion empire allowed Saint Laurent and Bergé to indulge their fantasies to an extent that might never be surpassed; constructing a series of extraordinary interiors, whose inspiration was intensely personal, a window, as it were, onto two shared lives, and as such, entirely outside the contemporaneous bourgeois attitudes to decoration. Each and every place, be it the French capital, the South of France or North Africa, had a unique, context-specific and immediately identifiable character and setting, with its own decorating rules, which were strictly adhered to, and in turn, defined how those spaces were used. The pair were largely immune to trends, and for that matter, what was happening en masse in the world of interiors, and instead, it was a carefully constructed, intensely personal ideology that compelled the way in which they lived day to day, encompassing not only matters of decoration, but ritual and routine, such as the meals that were prepared, which in consequence, determined which table service was used, and, for that matter, the complete tableau. As such, it can be seen as cyclical, in terms of their lifestyle and tastes dictating their interiors and vice versa, becoming akin to a manifesto; so much more than a shallow, superficial desire for aesthetically pleasing interiors, it went to the heart of who they were as people. French poet Robert de Montesquiou (1855) compared the house in which one lives to a state of mind, and to some extent, each and every one of Saint Laurent’s homes can be seen as a facet of his inner psyche; he wanted chintz for the house in Tangier to make believe it had belonged to an English couple, and the reason for his minimally appointed eyrie, or “bachelor studio”, on Avenue de Breteuil was that he needed a calm, simple space, with clean lines and white walls, in which to relax and decompress away from the intensity of his art-saturated Art Deco duplex, telling storied French decorator Jacques Grange (b. 1944) he wanted: “Something out of a film by Michaelangelo Antonioni … a studio that is light, a place to work. At the rue de Babylone I’m suffocated.”

A dining room, lined with an early nineteenth-century papier peint, designed by Roberto Peregalli and Laura Sartori Rimini, the duo behind interior design firm Studio Peregalli, photograph by Roberto Peregalli

Of course, without the innate talent of Grange, himself an avid collector, Saint Laurent and Bergé might never have achieved such iconic interiors: stripped-back modernism for Avenue de Breteuil, Orientalist for Jacques Majorelle’s Villa Oasis in Marrakech and a Proustian reliquary, with bedrooms named after the characters in À la recherche du temps perdu (Remembrance of Things Past) (1913) for Chateau Gabriel in Normandy, with its Russian dacha folly in the grounds. “Yves worked in his imagination,” explains Grange. “He thought [Chateau Gabriel] would be suitable for throwing grand balls filled with beautiful people. I think he did it twice. He grew tired very quickly.” Undoubtedly, it was the couturier’s molasses-dark, oak-panelled Paris salon (reputedly remodelled by maître of minimalism Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941) in the 1930s, though never proven), a veritable Aladdin’s cave of twentieth-century design treasures, including, non exhaustively, Africanist stools by Pierre Legrain (1889-1929), Eileen Gray’s (1878-1976) extraordinary Fauteuil aux Dragons (“Dragons” armchair) (c. 1917-1919) and a pair of monumental “dinanderie” vases (1925) by Jean Dunand (1877-1942), that most enraptured the public’s attention. This medley of Art Deco treasures were set off against works by Picasso (1881-1973), Matisse (1869-1954) and Mondrian (1872-1944), Old Master paintings by Goya (1746-1828), Ingres (1780-1867) and Géricault (1791-1824), Italian Renaissance bronzes and whimsical zoomorphic furniture by longtime friends Claude (1925-2019) and François-Xavier Lalanne (1927-2008). Compelled by beauty and quality, as opposed to a rigid, clear-cut approach, Saint Laurent and Bergé were extremely eclectic in their choices, and what truly unified the collection was the excellence of each and every object.

It’s important, perhaps, that one gives their interiors sociological and societal context; at the time France thought of itself as ultra-contemporary, with designers, such as Pierre Paulin (1927-2009) and Olivier Mourgue (b. 1939) creating futuristic, biomorphic furniture reflecting a space age sputnik aesthetic that permeated the 1960s and 70s. At rue de Babylone Saint Laurent and Bergé chose to sidestep entirely prevalent themes in interior design, paying little heed to diktats, colours and codes, instead, rekindling the decorative arts of the 1920s and 30s at a time when now acclaimed dealers, such as Félix Marcilhac (1941-2020) and Anne-Sophie Duval — who shared the duo’s same proclivities for furniture by the likes of Pierre Chareau (1883-1950), Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann (1879-1933) and Gustave Miklos (1888-1967) — had barely made a dent in the European market. “I ask myself where I found the time to collect all these objects and paintings. I think it’s admirable, and my choice of word is not exaggerated, that our tastes never clashed,” Bergé wrote in a letter to Saint Laurent after his death. “Deep down, our collection and our house were the greatest proof of our love for one another.”

As one of the great style arbiters of the twentieth century, it’s easy to think of Saint Laurent as the driving force behind their collection, but the couturier was oft quoted as saying that in the future, in matters of style and taste, we will speak of le goût Bergé, just as one refers to le goût Noailles or le goût Rothschild, and when one considers the unique art de vivre expressed in the extraordinarily refined art trove Bergé amassed in his eighteenth-century apartment on rue Bonaparte, one can see the niveau de chic raffiné, and occasional osé, in which he approached collecting. “I don’t know where my taste comes from … it’s a mystery. My family never had the least interest in the arts or knew anything about them, and surrounded themselves with hideous furniture, paintings and objects.” Bergé opined. “As a child, I sought refuge in books, and didn’t care for museums. What happened? … I don’t know. In any case, one day, just like finding one’s faith, or discovering that one is speaking a foreign language, I realised that I knew. [Saint Laurent and I] met at the same time. I’ve always thought it wasn’t fortuitous. [He] listened to me, [he] had absolute confidence in me; as with everything, [he] allowed me to hone my eye, refine my taste and above all find myself, as it’s there — in matters of taste — that it happened.”

The extraordinary home of Pierre Bergé, on rue Bonaparte, Paris, where in the dining room a suite of candle holders by François-Xavier Lalanne stand atop a Regency dining table, image c/o Sotheby’s

Similarly, if one looks to the world of contemporary interior design, in a continuation of the work of decorators such as Georges Geffroy (1903–1971) and Henri Samuel (1904-1996), Roberto Peregalli (b. 1961) and Laura Sartori Rimini, the duo behind interior design firm Studio Peregalli, continue to create cinematic spaces for a microcosm of collectors who are looking for homes that seem to have been carved out of time. Whilst the majority of their interiors are of a strongly historic bent, in the same way as Hubert de Givenchy (1927-2018) at Hôtel d'Orrouer and Manoir du Jonchet (or, for that matter, Joseph Achkar and Michel Charrière with their seventeenth-century Hôtel de Duc de Gesvres) they avoid academic reproduction or empty stylistic quotation; in the sense that, whilst their signature style might be traditionally leaning, their approach is not so much reproducing as reinventing, whereby a past that we might only dream of, that quite possibly never existed, is conjured up out of the ether, in interiors they refer to as “containers”, where the place’s previous life and current inhabitants merge. As the duo explain, “We have shared goals: a love of beauty, a sense of the power of details, an attention to the nuances of time.” Comparison can perhaps be drawn with French writer Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896), who turned a modest bourgeois domestic house into a proto-Symbolist work of art, documenting its extraordinary interiors in his 1881 book “La Maison d'un Artiste”. Goncourt, who collected, predominantly, eighteenth-century French and Far Eastern art considered a house to be an expansion of the body of the person who lives in it, in the same way, that the body in turn is a projection, an expansion, of the soul; ergo an interior, if successful, should reflect the innermost interests and passions of its inhabitants.

To that extent, it’s essential that designers and architects should have an understanding of art and design history, whether it be the distant past, recent past or present, all of which, considered as a whole, provides a bridge to the future, in terms of producing interiors that speak of our shared history. Peregalli and Rimini both acknowledge their projects would never come to fruition and remain “unrealised dreams” were it not a retinue of skilled craftspeople whom they rely on to fulfil their client’s exacting expectations. The duo for example designed the New York home of American artists John Currin (b. 1962) and Rachel Feinstein (b. 1971), who effusively sing the praises of Italian craftsmanship, suggesting no other country could satisfy their exacting idea of perfection; in the sense that, in respect of such artisans, knowledge and talent is inherited, their skills passed down from generation to generation, and as such, it’s the real deal, as opposed to a guesstimation, or rather, superficial reproduction of that which went before. Studio Peregalli’s refined interiors have been compared to the work of Italian film director Luchino Visconti (1906-1976), a gay, Marxist count, and a man of many contradictions, whose moody black and white movies were a languorous ode to such themes as idealised beauty, expectant mortality and the ruinous nature of power, all set against luxuriant backdrops of aristocratic hues. “The comparison with cinema is right because our houses are like series of images, room following room in a perspectival enfilade that should be read in its totality,” Rimini muses. “Every detail, from the furnishings to the texture of the walls in sunlight, contributes to this harmony.” Clients that understand and appreciate such an approach are for any passionate decorator a godsend, but they are, sadly, an increasingly rare breed, as a desire for uninspired, showy “newness” prevails over refined subtlety in a world where the desire to “be seen” reigns supreme. Fortunately, there are still a rarified few prepared to pay the price for truly exceptional interiors that transcend time and trends.

Ben Weaver