Aesthetic Voyeurs

Influences and Inspirations

“A collection is like a dinner party. It is made up of the people you invite, but also the people you don't.” — Pierre Bergé

With the advent of online influences, paid thousands of pounds a post to promote products to adoring fans, whether that be fashion or, increasingly, homewares, the term “influencer” is bandied about, often, it would seem, as shorthand for those with an eye for self-promotion and a follower base who hang off their every selfie. This is, as might be expected, nothing new, and before influencers, there were “tastemakers”, a concept that extends as far back as eighteenth-century France with the “Marchands-merciers”. Described by Diderot in his 1751 Encyclopédie as “merchants of everything and makers of nothing”, the merciers were at once importers, designers and interior decorators; responsible for launching avant-garde stylistic trends that came to define the French luxury savoir-faire that we still know today. Over time, the term tastemaker entered everyday parlance as shorthand for those who decide, or rather influence, either what is, or will, become fashionable. It’s a somewhat vague, ill-defined categorisation that could, in essence, relate to anyone with a grip on the zeitgeist, at any stage in the supply chain. Taking for example, the fashion world, those historically considered tastemakers include muses, such as Betty Catroux (b. 1945), Loulou de la Falaise (1947-2011) and Inès de la Fressange (b. 1957), designers and couturiers, the most famous of which being Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008) and Karl Lagerfeld (1933-2019), to groundbreaking fashion editors, the likes of Edmonde Charles-Roux (1920–2016), Diana Vreeland (1903-89) and Franca Sozzani (1950-2016), all of whom had a hand in teasing and manipulating the look of an era. There are, also, of course, patrons, those private collectors who foster and promote the work of artists, designers and artisans, with the sole aim of advancing visual culture, the archetypal example of which might be French fashion designer Jacques Doucet (1853-1929). Over the course of five decades, the couturier’s taste in architecture and objects d’art changed considerably; having started out obsessing over the crème de la crème of eighteenth-century douceur de vivre, he turned his back on antiquity, shifting his laser-sharp focus to the pinnacle of avant-garde modernism. Toward the end of his life, reflecting on his taste evolution, the childless couturier mused: “I was successively my grandfather, my father, my son, and my grandson”.

Doucet was an interesting character in that he was the first fashion designer to fuse his lifestyle with his professional persona, becoming something of a celebrity in his own right, and in turn, paving the way for Coco Chanel (1883-1971), Saint Laurent, Lagerfeld and Halston (1932-1990) et al. The proverbial belle of the époque ball, in tune with fashions of the day, the couturier commissioned society architect Louis Parent (1854-1909) to build him a hôtel particulier on rue Spontini, in the sixteenth arrondissement of Paris, its grandiose classical style evocative of the pre-revolutionary ancien régime. With the help of influential decorator-dealer Georges Hoentschel (1855-1915), Doucet proceeded to deck his cutting-edge des res out in an astonishing array of masterworks, including a highly unusual rococo armchair (carved to resemble blooming branches, now part of the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art), a ravishing terracotta sculpture by Clodion (1738–1814), depicting a satyr embracing a nymph, and a charming François Boucher (1703-1770) allegory of poetry. Merely five years after moving into his Louis XVI style petit palais, Doucet shocked the Parisian beau monde, selling the whole kit and caboodle at a four-day, record-breaking sale; the final tally being just under $3.1 million — the equivalent of $75 million in today’s money. Starting entirely afresh, the couturier moved into a lavish new apartment on avenue du Bois de Boulogne (the present-day avenue Foch), enlisting the haut monde of twentieth-century artists, decorators and designers to create its spectacular interiors. Cajoled and encouraged by writer and poet André Breton (1896-1966), future co-founder and principal theorist of Surrealism, whom Doucet had hired in 1921 as his librarian, the formally classically-inclined couturier was pushed to the cutting edge, acquiring numerous modernist masterpieces. A collection highlight was Picasso’s (1881-1973) seminal Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) (The Young Ladies of Avignon, originally titled The Brothel of Avignon), perhaps the most radical painting of the twentieth century; breaking entirely from traditional composition and perspective, and revolutionising the way in which artists saw and transformed reality.

The entrance to French couturier Jacques Doucet’s hôtel particulier on rue Saint-James, Paris, with its extraordinary silvered-iron staircase by Hungarian sculptor Joseph Csaky, photograph from L’Illustration

“Tête” (1923) by Joseph Csaky, a mesmerising rock crystal bust, entirely translucent, its hair picked out in a frieze of small engraved and gilded circles

It’s easy to forget how startling such works seemed to contemporary eyes, but Les Demoiselles was considered so controversial that when it was first shown, French artist André Derain (1880-1954), himself no stranger to new modes of representation, having co-founded Fauvism with Henri Matisse (1869-1954), suggested to Picasso that he might one day kill himself for the shame he had brought on the art establishment. Similarly, whilst readily accepting Picasso’s distorted and dislocated Cubist style, Doucet was not as immediately enamoured by the shocking, avant-garde stylings of other modern masters; in the mid-1920s Masson and his close friend and surrealist comrade, French poet Louis Aragon (1897-1982), took the couturier to visit the studio of Catalan artist Joan Miró (1893-1983) in the Cité des Fusains in Montmartre. Doucet sat flanked by his compatriots, entirely unsure what to expect, while Miró’s dealer Jacques Viot (1898-1973) stood lingering in the background. One after another, Miró placed his canvases on an easel for Doucet’s inspection. The first were a series of still lives, derived from Cubism, painted in a sharp, crystalline manner: “Quite incisive”, the couturier mumbled under his breath. But as Miró began bringing out painting after painting from which ordinary reality, even the fractured, fragmented version the Cubists represented, had vanished entirely, Doucet lapsed into Sphynx-like silence. It wasn’t until the patron was out on the street again that he finally spoke up: “Well my young friends, you have fooled me often, but you won’t fool me this time. Your friend is mad, stark mad, and that man in the corner was his keeper. While in there, I said nothing, for fear that he might grow excited. Why, he might have taken his brush and splashed it on my face!” This had, however, without his realising, been something of a formative experience, as just three weeks later, he told Masson effusively: “You know, I have bought two paintings by that friend of yours,” adding, “I have hung them at the foot of my bed. When I wake up in the morning, I see them, and I am happy for the rest of the day.”

When it came to furnishing his modernist eyrie, the couturier was similarly strong-willed, and during the course of commissioning works from some of the most exceptional makers in Paris, he rubbed certain artists and artisans the wrong way. “If I had a pair of scissors, I would cut off those horrible tassels,” Irish architect Eileen Gray (1878-1976) later lamented of the extraordinary and exotic “Lotus table” (1915) she designed for Doucet, which, at his instance, she decorated with roped silk cords, each terminating in amber balls and voluptuous silk plumes. Gray trained under lacquer maître Seizo Sugawara (1884-1937), and this remarkable work of art speaks of her mastery of the laborious, almost forgotten technique of Japanese Urushi. Sheathed in dark green lacquer, its delicate legs, carved to represent clusters of lotus flowers, are topped by elegant white blossoms, evocative of the sort of stylised capitals seen in the temples of Ancient Egypt. However, despite the magnificence of his Avenue du Bois apartment, it wasn’t until 1928, when Doucet upped sticks and moved to his wife’s hôtel particulier on rue Saint-James, in the affluent suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine, that he was able to let his imagination truly run riot. Upon entering this spectacular modernist masterpiece, a silvered-iron staircase, punctuated by elegant bas-reliefs, the work of Hungarian sculptor Joseph Csaky (1888-1971) (also of note, another work commissioned by the couturier is the artist’s “Tête” (1923), a mesmerising rock crystal bust, entirely translucent, its hair picked out in a frieze of small engraved and gilded circles), ascended to a glorious enfilade of three cavernous reception rooms. Whilst the modernist mantra might be defined by German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's (1886-1969) pithy aphorism “Less is more”, Doucet’s collection was very antithesis of such minimalist proclivities, with every square inch so packed with works of art, that they were somewhat evocative of the busy belle époque rooms he created at rue Spontini. Works by Picasso, Chagall (1887-1985) and Max Ernst (1891-1976) jostled for attention, rubbing shoulders with palm wood and coral lacquered banquettes by Gustave Miklos (1888-1967) and Marcel Coard’s spectacular Canapé Gondole (c. 1925). This boatlike Indian rosewood canapé, inlaid with rows of ivory and entirely covered in strips of wood carved to resemble basketry, is perfectly demonstrative of Coard’s skill as an ébéniste. Doucet died in 1929, living just long enough to see his studio’s completion, after which, following the demise of his fashion house, the entire assemblage of furniture and art was sold off in 1972 in a sale held at Hôtel Drouot; snapped up by Paris’ design cognoscenti, with farsighted bidders including Lagerfeld, Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé (1930-2017).

Patroness and collector Marie-Laure de Noailles, pictured here at her hôtel particulier at 11 Place des États-Unis, wearing a gown by Schiaparelli, photograph by Norman Parkinson

The home of Marie-Laure de Noailles, decorated by maître of minimalism Jean-Michel Frank, with parchment walls and furniture in straw marquetry, photograph by Thérèse Bonney

Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles (1902-1970) was another at the epicentre of the Parisian avant-garde; patron and muse of countless artists, filmmakers and musicians such as Man Ray (1890-1976), Luis Buñuel (1900-1983), Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), Salvador Dali (1904-1989) and Francis Poulenc (1899-1963). Though today, perhaps above all else, it’s her collaboration with ascetically inclined decorator Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941), which resulted in the parchment-clad interiors for her grand Belle-Epoque mansion at 11 Place des États-Unis, that has had the most profound impact on the world of interiors; its pared-back, ton-sur-ton palette and white, slip-covered sofas still copied by myriad designers around the globe. While Marie-Laure’s storied salon sighed under the weight of a cacophony of treasures, from academy to avant-garde, a veritable testament to the beauty afforded by wealth, more important was the impetus behind the collection, that being, to celebrate and encourage artistic talent. As biographer, aesthete, novelist and dandy Philippe Jullian (1919-1977) wrote in “Une des maisons clés pour l’histoire du goût au XXe siècle”, Connaissance des arts, no. 152 (October 1964), “From the vault, a tall Max Ernst and a car compressed by [the Nouveau Réalisme artist] César shout: ‘You are not entering here to evoke the splendours of capitalism or the elegance of the aristocracy, you are with curious minds who will play you more than one trick.’” Of course, contemporaneously speaking, it came as something of a shock to those with a disposition less art moderne, and more petit bourgeoisie, with the Abbé Mugnier (1853-1944), for example, a priest popular in Paris salons noting: “It was all very white, naked, strange.”

The home of Marie-Anne Derville, Paris, in the study a Pierre Chareau chair and an enamelled stoneware sculpture by Maurice Gensoli, photograph by Dominique Nabokov

As an entity, Marie-Laure was not necessarily an easy character to get along with, as Francine du Plessix Gray (1913-2019) recalls, upon being sent by Elle magazine editor Jean-Dominique Bauby (1952-1997) to interview the fabled patroness for an article on French collectors. Arriving at the great gates of the Hôtel Bischofsheim, a liveried valet led the fledgling journalist past a Van Dyck (1599-1641) and two Goya’s (1746-1828) into the Grand Salon, where Rubens (1577-1640) rubbed shoulders with Yves Tanguy (1900-1955), and sixteenth-century Cellini (1500-15710 bronzes stood watch over portraits of Marie-Laure by Balthus (1908-2001), Dora Maar (1907-1997) and Picasso. After a brief conversation, the Vicomtesse, who stood in a corner, smoking, her pale, aquiline face, framed by a mop of wild black hair, paused and posed a somewhat unexpected question: “Men who love Proust have short penises, don’t you think?” Caught entirely off guard, Gray, who went on to become a Pulitzer Prize-nominated writer, failed, off the cuff, to formulate a sufficiently witty retort. Marie-Laure looked at her watch and, in crisp British-accented English, replied curtly: “I must go. I have a date with my gyno in twenty minutes.” Whilst Marie-Laure generally disliked women and was notoriously rude to them, this somewhat bizarre exchange might, to some extent, be explained by her friend, the composer and author Ned Rorem (1923-2022), who wrote his journal (“The Paris Diary and The New York Diary, 1951-1961”): “Marie-Laure is first of all a child, second an artist, third a Vicomtesse … Fourth, she’s a saint, fifth, a masochist … and sixth, a bitch … Above all, she is generous, not to mention crazy.” Somewhat extraordinary, within their lifetimes, Marie-Laure and her husband, fitness fanatic and art enthusiast Charles de Noailles (1891-1981), whose nonconformist tastes were somewhat unusual in an aristocrat, assembled an incomparable collection of painting and sculpture, which, in its breadth and diversity, included almost every member of the European avant-garde. Indeed the Noailles, through their collection and patronage, took exceptional pleasure in shocking people, and as their friend and fellow mega collector Pierre Bergé put it to a French television interviewer, Charles and Marie-Laure “found their own equilibrium by exerting a destabilizing influence on other people.”

Aside from their Paris quarters, when Marie-Laure fell pregnant with her first child, Laure de Noailles (b. 1924), they set about looking for an architect for a villa they wanted to build on the ruins of the medieval castle of Hyères, in the South of France. Having initially been refused by architect and director of the Bauhaus School in Germany Mies Van der Rohe, who was, as it transpired, far too busy to take them on, they turned to ideologically driven non-conformist Le Corbusier (1887-1965); but, quelle surprise, his imperious personality and didactic, doctrinaire approach proved too much of a personality clash. As such, the art collecting duo settled on an up-and-coming French modernist by the name of Robert Mallet-Stevens (1886-1945), who during the course of his illustrious career would go on to become a master of Streamline Moderne. The commission called for a “small, interesting house to live in”, the resulting creation, the architect’s magnum opus, was a rambling, forty-bedroom house, composed of concrete, glass and chrome; its chiselled façade resembling the low-lying, elongated silhouette of elegant Art Deco ocean liner. “Innumerable rooms, rectilinear, unicolored” was the way in which painter, illustrator, theatre designer and author Jean Hugo (1894-1984) described the house in his memoirs. “Like the blocks of a child’s game tumbling one into the other, forming a strangely obscure labyrinth in which guests constantly lost their way.” The triangular Cubist garden, designed by Armenian architect Gabriel Guévrékian (1892-1970) was equally extraordinary, at its centre a rotating sculpture, Jacques Lipchitz’s bronze, La joie de Vivre (The Joy of Life), a dancing couple, large enough to be seen against the sky, carrying an inscription paraphrasing French writer Baudelaire (1821-1867), “J’aime le mouvement qui déplace les formes” (I like the movement that moves the shapes). In addition to Mallet-Stevens and Guévrékian, a veritable who’s who of modernism, including Pierre Chareau (1883-1950), Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931), Eileen Gray, Henri Laurens (1885-1954), Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973), and Jan (1896-1966) and Joël Martel (1896-1966) all contributed to the creation of this remarkable edifice. Marie-Laure lived without fear of social condemnation, and within the confines of her white-walled modernist citadel, she entertained her cabal of artists, writers, poets and filmmakers with the sort of baroque decadence that would have been familiar to her noble forebears; who, on her mother’s side, included self-proclaimed paedophile, rapist, torturer, and eloquent literary apologist for sexual cruelty, the Marquis de Sade (1740-1814) and the acid-witted Comtesse de Chevigné (1859-1936), a model for the Duchesse de Guermantes in Marcel Proust’s (1871-1922) seminal work À la recherche du temps perdu (“Proust? We read it to get news of friends”, Charles once quipped). This devoted collectionneuse, through her unique and singular vision, like Douquete, continues to provide a constant source of fascination and inspiration. Interestingly, much later in life, Marie-Laure liked to ask new friends the question: “At what age did you become yourself?”

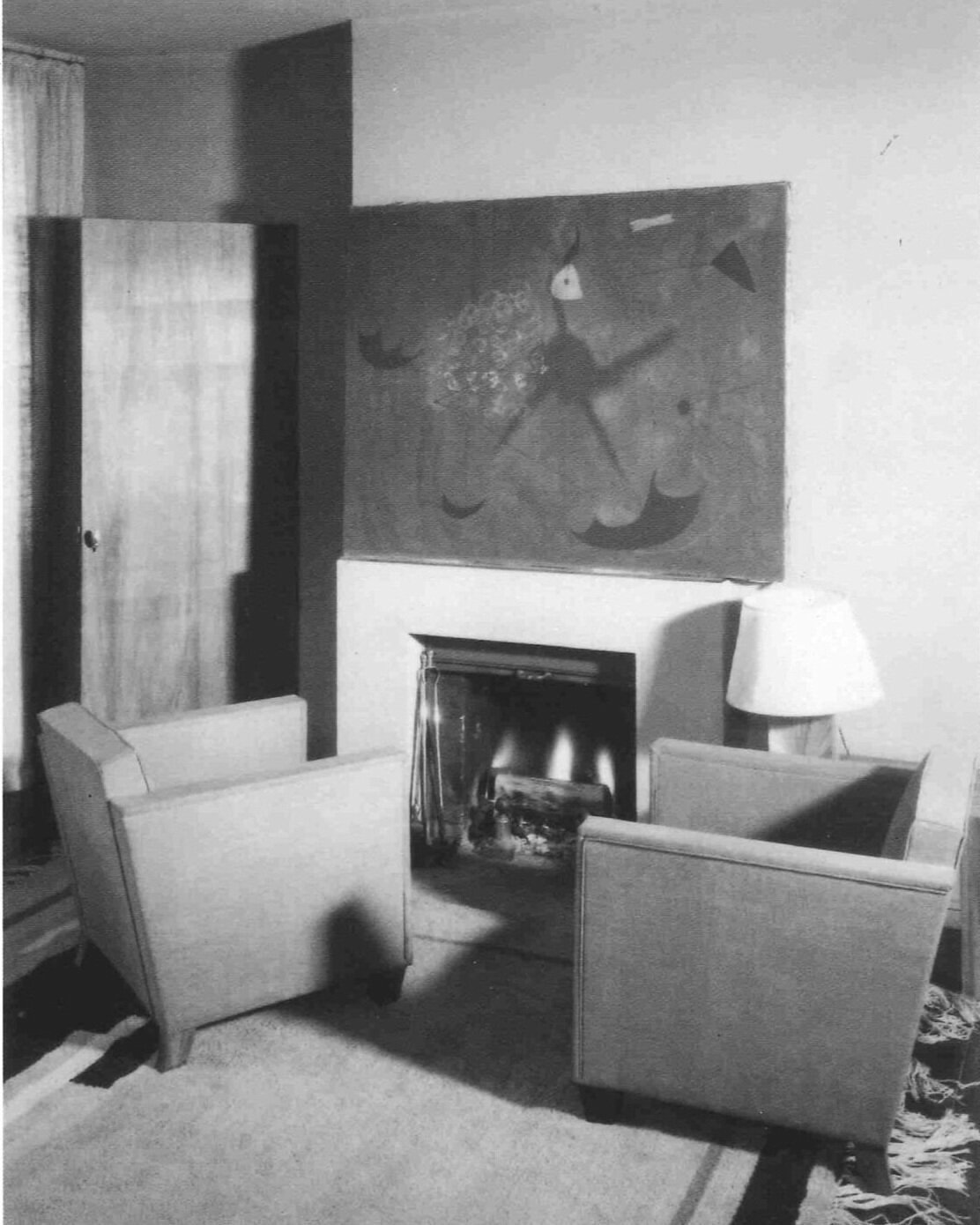

An interior by American decorator Eyre de Lanux, where, in the sitting room a canvas by Catalan artist Joan Miró hangs above the plaster fireplace.

Some people are blessed with supreme confidence of character and taste from a very early age, while others take time to fully realise their own personal aesthetic, as a result, not only of the art, interiors and architecture they’re exposed to, or the literature they read but also meeting new people, through whom one might identify previously unexplored avenues, in terms of art, interiors and architecture. Social media, and in particular, Instagram, has led to the democratisation of the design industry, in the sense that, we’re able to see the homes and collections of people around the world in a way that would previously have been entirely unattainable for the majority. As such, we’ve all, to some extent, become aesthetic voyeurs, keen to see what supposed tastemakers are putting in their own homes. Of course, for those working in the interior design industry, this can sometimes stifle creativity, in the sense of second-guessing choices, based on the taste of others. “Digitalization has led to information overload, where the same images spin over and over again on social media platforms. This has in part resulted in a uniform design language across the industry that tends to repeat itself,” explains Stockholm-based interior architect Niki Rollof. “Therefore, I try to seek inspiration from different kinds of sources, such as music, film and art, all of which can provoke both nostalgia and forward-thinking, in the sense that you can travel within it to wherever you want to be. To lean on such mediums, instead of digital imagery, for instance, allows me to escape into my own imagination.” However, for those of us still seeking to define, or perhaps, refine, our own personal sense of style, social media can provide something of a formative education. Indeed there are people I’ve met who completely changed my attitude to say, an artistic medium, for example, I’d never been particularly drawn to photography before meeting Julien Drach (b. 1973) and Carolyn Quartermaine (b. 1959), whose photography blurs the boundaries between artistic mediums, having a painterly depth evocative of the work of Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916), or, a more direct comparison, the innovative, cinematic style of Surrealist and Dadaist Man Ray (1890-1976) (who, as it happens, baulked at being called a “photographer”, considering himself a painter and artist above all else).

Similarly, there are those whose unique aesthetic, outwith the repetitive doldrum of mainstream media trends, is always interesting to see; in terms of interiors, for example, designers such as Michael Bargo, Marie-Anne Derville and Camille Vergnes, who use art moderne in a way that feels fresh and exciting, and as far as fashion is concerned, Dessert Vintage, Luca Di Stanio and Dag Granath are equally intelligent in their references. An art world insider, who frequently travels for work, recently bemoaned the fact that compared to Los Angeles, New York has become somewhat staid and set in its ways, too concerned, like Paris, by projecting a stereotypical image, resulting in a lack of openness to new ideas and genuine creativity. Similarly acerbic, Another Man editor-in-chief Ben Cobb (b. 1976) wrote last week in an editorial: “The glamorous NY dream is long gone. As I boarded my return flight [to London], I thought about a disco when the lights come up and you know it’s time to go home.” Whether or not NYC is in actual fact in a terminal state of decline, at least apropos interiors and architecture, LA is, in essence, doing what America has, for much of the twentieth century, done so well, as demonstrated by designers such as Frances Elkins (1888-1953), Billy Baldwin (1903-1983) and Jed Johnson (1948-1996); taking European style and making it more relevant to a contemporary way of living. This can be seen to great effect with an intelligent curation of Art Deco design at galleries Seventh House and Formative Modern, the latter of which recently created elegantly appointed interiors for cult jewellery designer Sophie Buhai’s new 1980s post-modern atelier. Sources of inspiration needn’t, necessarily, be the biggest names, but rather those who strike a chord on a personal level, whose aesthetic choices might open one’s eyes to new styles, colours, fabrics, and even ways of displaying, or juxtaposing works of art and design from different periods. Today there’s such variety, it’s very easy to forget that those such as the Noailles, Saint Laurent, Roger Vivier, Hubert de Givenchy (1927-2018) and Henri Samuel (1904-1996), who hung works by Poliakoff (1900-1969) or Picasso above an eighteenth-century commode, or positioned a Roman Torso so as to be in conversation with a flower festooned Lalanne (1925-2019) mirror were considered radical. After the twentieth-century whirlwind of invention and re-invention that saw style after style emerge from the ashes of two world wars, from the extravagance of Armand-Albert Rateau’s (1882-1938) luxurious, baroque style, to the neo-classical minimalism of Jean-Michel Frank and Marc du Plantier (1901-1975), to Jean Royère’s (1902-1981) whimsically inclined biomorphic creations, culminating in the space age futurism of Wendell Castle (1932-2018) and Marc Newson (b. 1963), it’s unlikely we’re going to see a complete reinvention of the wheel anytime soon. As such, perhaps it’s time we looked to the smaller things, whether that be an unusual use of materials, a la Eyre de Lanux (1894-1996), or simply a nuance for form and colour that encapsulates the most elusive, yet seductive of style attributions, namely, chic.