Fashion Fades, Style is Eternal

Couturier’s and Their Interiors

"Fashions pass quickly, and nothing is more pathetic than those puppets of fashion outrageously made up one day, pale the next, pleated or ironed stiff, libertine or ascetic. Playing with fashion is an art. The first rule is don't burn your wings." - Yves Saint Laurent

The role of a couturier is interesting in that, whilst no one would write under the name of say Marcel Proust (1871-1922), or paint signing Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), fashion houses, generally, live on, under the creative auspices of a succession of designers, none of whom might share the slightest DNA with their forefathers (as can be seen, for example, with Demna Gvasalia (b. 1981) at Balenciaga or Alessandro Michele (b. 1971) at Gucci), or, for that matter, care about maintaining the ethos or aesthetic for which the brand is known. That needn’t, of course, necessarily be the case, as with polymath par excellence Karl Lagerfeld (1933-2019) at Chanel, who, by creating an up-to-date dialogue between house codes and Pop Culture, resuscitated an ailing brand that, by the 1990s, had become so desperately dated it was considered by many a “dead house”, and turning it into a fashion world behemoth worth $53 billion. It was the couturier’s innate ability to modernise and re-contextualise brand heritage, in a way that seemed consistently fresh and au courant, that, decade after decade, hooked and lured in a younger, more fashion-savvy clientele; to the extent that, having been, in essence, a staple for bourgeoisie housewives, the brand can now count, amongst its many loyal customers, billionaire pop mogul Rihanna (b. 1988), “nepo baby” and actress Lily-Rose Depp (b. 1999) and Gen Z pop songstress Olivia Rodrigo (b. 2003). This was in part due to “Kaiser Karl’s” innate understanding of the way in which the world was changing, and how status, in terms of wealth and success, was moving from discreet, “quiet luxury” to brand-driven, showy ostentation (fashion is, of course, nothing if not cynical, and we’re now seeing a return to the idea of “stealth wealth” and understated dressing as spurred on by brands such as The Row and tailoring house Atelier Saman Amel).

Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel (1883-1971) was remarkable, first and foremost, for her extreme perspicacity and tenacious nature; born in a poor house hospice, at a time when women were expected to become “homemakers”, she managed to establish herself as one of the most successful couturiers of the twentieth century, and, arguably, the most famous designer in history, with her reputation easily outstripping that of rivals such as Jeanne Lanvin (1867-1946), Christian Dior (1905-1957) and Pierre Balmain (1914-1982). Perhaps a telling insight, in a rare moment of candour Chanel explained to her biographer Louise de Vilmorin (1902-1969): “I was a child in revolt. Proud people desire only one thing: freedom. But to be free, one must have money.” Even ignoring rampant misogyny and the prevalent patriarchal psyche, she had class discrimination to counter, which was, at the time, flagrant; even surrealistically inclined couturier Elsa Schiaparelli (1890-1973), who, after being abandoned by her husband, a con artist and self-professed “paranormal expert”, was embraced by Parisian society, in large part due to her aristocratic lineage, refereed to Chanel dismissively as “that dreary little bourgeoisie” and “that milliner” (Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895-1972), meanwhile, who was, to some extent, a product of both worlds, the son of a mariner and a seamstress, who, as a teenager, found himself under the patronage of Blanca de Aragón y Carrillo de Albornoz, Marchioness de Casa Torres (1892-1981), was equal opportunities in terms of insults, rather cuttingly, describing Chanel as having “very little taste, all of it good”, and Schiaparelli, meanwhile, having “lots of taste, all of it bad”). Despite Chanel’s humble beginnings, her clothing, has historically, been associated with the aesthetic of “old money”, with her elegant tweed suits worn by everyone from Princess Diana (1961-1997) to Diana Vreeland (1903-1989) (who Chanel remarked was the most affected woman she had ever met); with American First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy (1929-1994), wearing a replica of a pink suit from the fashion house’s Fall/Winter 1961 collection the day her husband, American President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) was assassinated (it was expected a patriotically minded First Lady would represent only home-grown talent, and so, as to avoid scrutiny, fabric, buttons and trim were sent from Paris, and the suit was made by Park Avenue salon Chez Ninon, using Chanel’s approved “line for line” system).

Couturier Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel in the salon of her Coromandel-clad apartment at 31rue Cambon, Paris (1959) wearing one of her signature tweed suits

La Pausa, Chanel’s rambling seven-bedroom villa she built on the cliffs of La Toracca, between Monte-Carlo and Menton, modelled on the twelfth-century Aubazine Abbey, where she spent her childhood

Chanel was something of a complex character, to say the very least, as despite, on the one hand, defying societal and gender norms, dedicating her life to imagining new ways for women to experience fashion, on the other, she was a Nazi sympathiser and informant who, throughout the duration of the Second World War, had a well-documented relationship with Nazi officer Hans Günther von Dincklage (1896-1974), a German Abwehr spy, propagandist, and special attaché to the German Embassy in Paris. Somewhat chillingly, Hal Vaughan’s (1929-2013) Sleeping With The Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War (2011) provides evidence she was actively involved in Nazi missions, had an agent number (F-7124) and even a code name, Westminster, after her former lover, Hugh Grosvenor, second Duke of Westminster (1879-1953), Britain’s richest man with an estimated income of a guinea per minute. The Duke, known to family and friends as “Bendor” (after his grandfather’s Derby-winning stallion), was, at the time, married to his second wife, Violet Mary Nelson (1891-1983), and, after meeting Chanel at a party in Monte-Carlo, he spent months wooing her, before the couple embarked upon a decade-long affair. It was around this time the couturier began embellishing and romanticising the story of her childhood, spinning the rose-tinted yarn that after her mother’s untimely demise, her father had set sail for America, seeking wealth and fortune in the “New World”, leaving her to live under the dutiful protection of two unmarried “aunts” who dressed entirely in grey and black. This was a thinly veiled allusion, one would presume, to the tunics of the nuns that raised her: “My aunts were good people, but absolutely without tenderness, I was not loved in their house.” Spending time together at the Duke’s numerous and lavish estates, the couturier took inspiration from the sartorial habits of the English upper classes, with fishing and hunting attire being the basis for her celebrated tweed collection. It might come as no surprise then, that in her third-floor apartment at 31 Rue Cambon, Chanel adopted many of the decorating tropes associated with pedigreed European families, at least in part, so as to better reflect and cement her newly acquired social standing. Despite her humble beginnings, the couturier had a preternatural talent for the aesthetic, which brings to mind collector and philanthropist Pierre Bergé (1930-2017), the son of a tax official and a school teacher, who once explained: “I don’t know where my taste comes from … it’s a mystery. My family never had the least interest in the arts or knew anything about them, and surrounded themselves with hideous furniture, paintings and objects.” In a similar way, Chanel’s innate style can be attributed to nature, rather than nurture, which chimes with her opinion that, “an interior is the natural projection of a soul”. At rue Cambon that meant an earthy palette of black, gold, brown, honey and cinnabar which, along with the gilt-gold woodland scene that frames the salon’s marble mantelpiece, took its inspiration from the fantastical and highly fashionable murals painted by her close friend, Spanish artist José María Sert (1874-1945) (whose wife, Misha (1872-1950), a patron of contemporary art and music, who, according to Australian critic Clive James (1939-2019), had a “legendary pair of legs and a bosom that kept strong men awake at night”, was Chanel’s “soul sister”, and likely lover).

Couturier Karl Lagerfeld's extraordinary Art Deco apartment, a style he described as the roots of “this modernity that I am tirelessly searching for”, photograph by Horst P. Horst for Vogue, September 1974

The dining room of Lagerfeld’s eighteenth-century hôtel particulier, Paris, with a suite of Louis XV chairs and a table draped in Venetian lace, photograph by Oberto Gili for Vogue, April 1989

This extraordinary series of rooms are highly personal, as can be seen, for example, in the elegant rock crystal chandelier gracing the main salon (see above), which was a bespoke commission, attesting to the couturier’s belief in the stone’s healing powers, with its wrought iron frame concealing a veritable treasure trove of symbolism, glimpsed in fleeting moments, including the Chanel number “5”, the double “C’s” of the brand logo, “G” for Gabrielle and “W” for Westminster. Indeed the decor throughout is redolent of the temples of Ancient Egypt, in terms of layer upon layer of meaning, in a similar vein to Italian architect Carlo Mollino’s (1905-1973) mysterious, shrine-like apartment in Turin. Influenced by another of her lovers, English polo player Arthur “Boy” Capel (1881-1919) (in the obituary of one of Capel’s daughters, he was described as “an intellectual, politician, tycoon, polo-player and the dashing lover and sponsor of the fashion designer Coco Chanel”), the couturier bought some forty antique coromandel folding screens — their lacquer panels decorated with fans, animals, rocky landscapes and, of course, her beloved Camellia flowers; which she mounted wall to wall, in the manner of panelling, or, as a result of her aversion to doors, which she loathed, used them as dividers, enclosing seating areas and reshaping rooms; as Chanel archivist Odile Babin explains, rather curiously, “She hoped that by placing them in front of the door, her guests might not remember to leave”. Of course, famously, Chanel never slept at her elegantly appointed rue Cambon crash pad, instead, making the short sling-backed walk to the Ritz hotel on Place Vendôme, where she kept a neutrally hued suite, replete with a seventeenth-century painting by Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), court painter to Louis XIV (who declared him “the greatest French artist of all time”), depicting the ritual slaying of Trojan princess Polyxena; one might almost surmise, given her proclivities that she had an aversion to being alone, which might, in some part, stem from a feeling of abandonment as a child. Interestingly, given Chanel’s predilection for symbolism, the initials CLBF in the corner of the canvas stand for Charles Le Brun Fecit, the latter, being a Latin word translating as “he (or she) made it” — a detail that must surely have amused Chanel, who went from orphan to patron of the arts. Somewhat extraordinarily, the work’s provenance was re-discovered only in the Summer of 2012, when, for the first time since César Ritz (1850-1918) opened the hotel in 1898, it closed for refurbishment, necessitating a large-scale inventory. Nobody knew the painting was there, or that it even existed, there’s no record of purchase or installation in the Ritz archives, and it’s quite possible, given her relationship with Von Dincklage, that Chanel smuggled it in quietly during the German occupation of Paris, casting a rather dark shadow over an otherwise remarkable masterwork.

The dining room of Chanel’s “La Pausa”, in the South of France, which she decorated in a strict palette of neutrals, offset with dusky pinks and pale greys

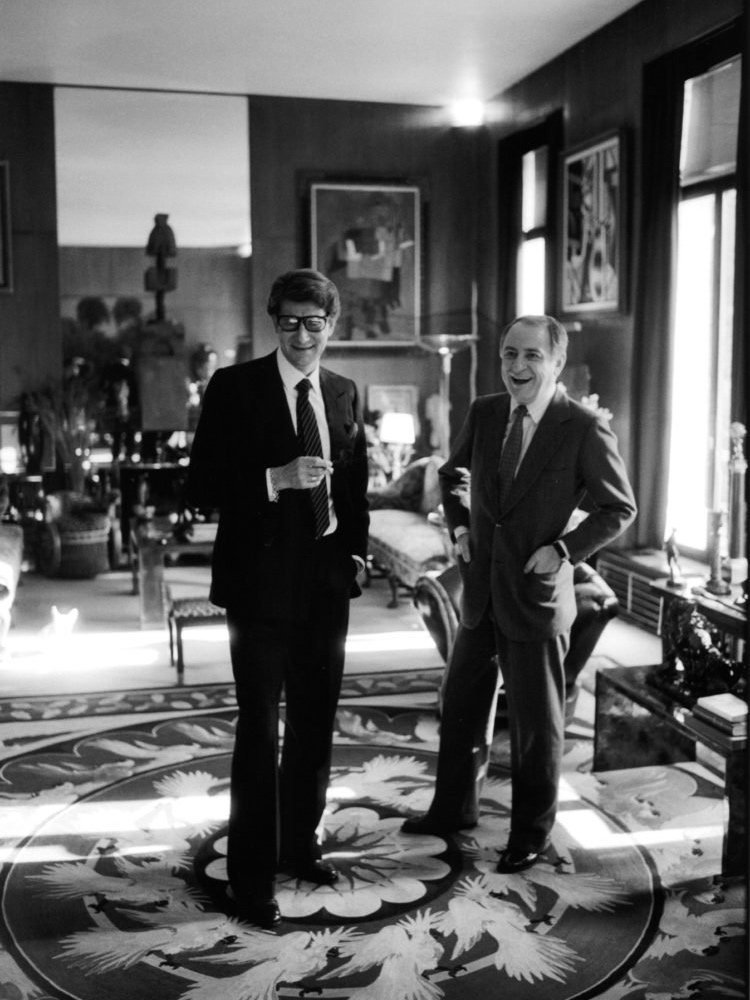

French couturier Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008) and his partner Pierre Bergé (1930-2017) in the now iconic Art Deco salon of their rue de Babylone apartment

Amongst numerous treasures accumulated by Chanel at rue Cambon were a menagerie of animal sculptures, lending her interiors a certain air of exoticism. These included birds, horses, a Venetian lion, representing her astrological sign of Leo, and a wonderful pair of almost life-size bronze deer, both of which she acquired personally from the collection of the infamous heiress, muse and patroness of the arts Luisa Casati, Marquise Stampa di Soncino (1881-1957). Casati was one of the wealthiest women in Europe, who, having fallen for the legendary charms of Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938) (a prototype fascist who paved the way for Mussolini), turned her back on conventional society to realise her ambition of becoming “a living work of art”. Casati led a life of otherworldly excess, commissioning Europe’s leading couturiers to make her every public appearance a spectacle to behold, starting with none other than Spanish polymath Mariano Fortuny (1871-1949), wearing his brocade velvet clocks for her daily peregrinations around Piazza San Marco; where she was chaperoned by a tall, black manservant, tasked with the unedifying role of carrying a feathered parasol, so as to protect her from the mid-day sun, whilst at the same time, negotiating her two pet cheetahs, who were, both, naturally, outfitted in bejewelled collars and, allegedly, tamed with small doses of opium. By 1930, having amassed personal debts of some $25 million, which equates to an almost unbelievable $400 million in today’s money, Casati faced financial ruin; unable to pay her creditors, her property and personal possessions were seized and sold off at the Palais Rose in Paris in 1932, at which Chanel was bidding. Aside from these various works of art and objets d’art, of particular note, especially to those in the interiors world, a tour de force of furniture design, the couturier’s now iconic, rolled-arm sofa — its elegant, suede-upholstered frame delicately outlined in brass nailheads and accented with fluted gilt oak feet; much-imitated over the years, it’s streamlined silhouette played a staring role in the Seattle apartment of fictional radio psychiatrist Frasier Crane (played by Kelsey Grammer (b. 1955)), in the eponymously named American prime-time sitcom.

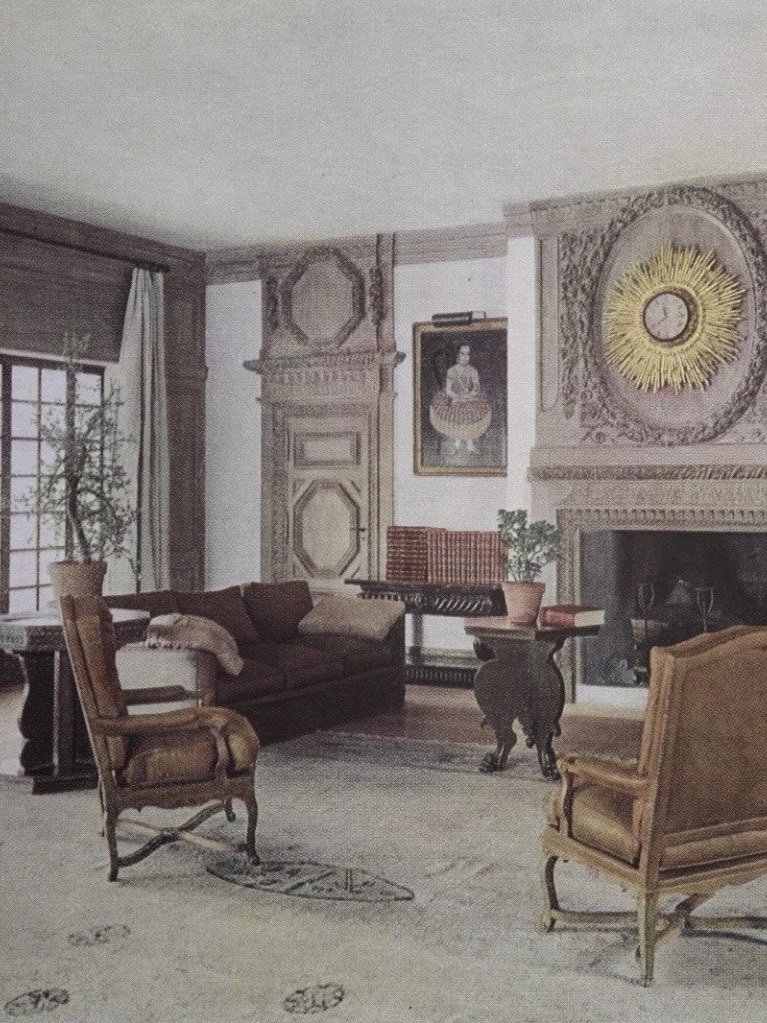

A case of art imitating life the apartment proved a constant source of inspiration to Chanel, for example, the pair of highly ornamented octagonal Venetian glass mirrors, framing the dining room chimney breast providing the inspiration behind her No 5 perfume stopper. With a flair for decorating, not only did she furnish her Parisian pied-à-terre, but also La Pausa, the rambling seven-bedroom villa she built on the cliffs of La Toracca, between Monte-Carlo and Menton, modelled on the twelfth-century Aubazine Abbey, where she spent her childhood. Rather charmingly, and somewhat more elegant, than say, “Casa Coco”, the name refers to a chapel that once stood on the site, where Mary Magdalene is said to have “paused” on her journey from Jerusalem following the crucifixion of Jesus. La Pausa’s pared-back monastic interiors are reminiscent of Chilean patron of modernism Eugenia Errázuriz (1860-1951), who was, coincidentally, muse and mentor to French ensemblier Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941), who, allegedly, designed the instantly recognisable mirrored staircase at Chanel’s rue Cambon atelier (where the couturier would sit unseen, cigarette in hand, observing reactions to her fashion shows below). For the decoration of La Pausa’s ton-sur-ton ivory-white rooms, in which, the couturier may have been assisted by Stéphane Boudin (1888-1967), president of storied French interior design firm Maison Jansen, she implemented a strict palette of neutrals, offset with dusky pinks and pale greys, which, neurotic in her pursuit of perfection, even extended to a bespoke beige grand piano. The salon, elegant in its austerity, was furnished sparely with eighteenth-century English oak panelling, French Régence armchairs and paintings from the School of Velázquez, all of which convey a luxurious yet ascetic air, a veritable entertainment gesamtkunstwerk; an all-encompassing principle extending as far as her generous, yet pared-back style of entertaining, with her menus hearty and rustic. As friend and Vogue fashion editor Bettina Ballard (1905-1961) recalled in her memoir, “The long dining room had a buffet at one end with hot Italian pasta, cold English roast beef, French dishes, a little bit of everything.”

A decade after Chanel’s death in 1982, her fabled couture house had become something of a grand old lady, rudderless, bourgeoise and, without innovation, entirely at odds with contemporary youth culture. Lagerfeld, then also working for Chloé and Fendi, realised Chanel needed more than a fresh lick of paint, and, in the process of breathing new life into a moribund label, he created a blueprint for what we now take for granted as the role of creative director. Whilst the couturier had enormous respect for and even, perhaps, psychic synchronicity with the past, he also appreciated the need for re-invention, to modernise and, most importantly (in a similar way to decorative arts dealers such as Félix Marcilhac (1941-2020) and Jean-Jacques Dutko), to re-contextualise timeless design for a new, contemporary audience; after all, for a brand to survive, it must attract new blood, catering to a freshly minted haute bourgeois which, by and large, has little or no interest in the then, only the now. Of his approach, Lagerfeld once quipped, “Anything dusty, dirty, musty—forget about it. I like my eighteenth-century fresh”. As such, rather than merely imitating brand heritage, he iterated on it, playing with a vocabulary of “Chanelisms” — such as tweed, quilting, gold chains, the camellia flower and double-C monogram — creating an up-to-date dialogue between such recognised codes and pop culture. As pithily put by journalist and editor Hamish Bowles (b. 1963), Lagerfeld “set out to change the fashion world by making something old new again”. Fully immersing himself in brand archives, Lagerfeld, like Chanel, took inspiration from the furnishings of her rue Cambon apartment. For one of the Kaiser’s most memorable catwalk shows, the spring/summer 2010 collection, in a nod to the gilt-gold “Wheat Table”, created by haute Parisian jeweller Robert Goossens (1927-2017) for Chanel’s Coromandel clad salon, models marched down a catwalk, wheat ears clinging to their Bardot-esque beehives, and for the finale, his bride and groom, quite literally, took a “tumble in the hay”, bales of which were piled up in banks around the Grand Palais. In the process of reinventing and reinvigorating Chanel, the couturier himself became something of an icon, with his quintessential uniform of fingerless gloves, pristine, starched white collars and powdered grey hair pulled into a tight, beribboned ponytail, going further than a “signature look”, and becoming something of a trade mark; so much so, that the couturier would later use his sunglass-clad silhouette as the logo for his eponymous, namesake label. Typically ahead of the curve, Lagerfeld approached his life as an aesthetic whole and as such, in a similar way to the third Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713) — whose “culture of politeness” placed an emphasis on the importance of understanding and appreciating the treasures of Greek and Roman antiquity, whereby classical ideals began permeating all areas of architecture and fashion — in terms of day-to-day life, the art of living well was an all-encompassing, far-reaching concept, extending far beyond inanimate spaces and objects, to manners, art, education and so forth.

Eileen Gray’s fantastical “Fauteuil aux Dragons”, pictured at Saint Laurent’s rue de Babylone duplex, which sold in February 2009 at Christie’s Paris for €21,905,000

Like Chanel, Lagerfeld was an insatiable collector, albeit on acid, creating myriad interiors throughout his lifetime, each approached as if an obsession; first, in the 1970s, it was Art Deco, which he described as the roots of “this modernity that I am tirelessly searching for”. One must remember, this was a time when, as a genre, early twentieth-century furniture by the likes of Süe et Mare, André Arbus (1903-1969) and Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann (1879-1933) was deeply unfashionable, and only recently had great gallerists such as Alain Marcelpoil, Jacques Lacoste and Cheska and Bob Vallois started to re-discover and re-contextualise such works. “The early interest of fashion designers and artists like Andy Warhol, Karl Lagerfeld and Yves Saint Laurent in Art Deco in the 1970s echoes the pivotal role of fashion designers such as Jacques Doucet, Paul Iribe, Paul Poiret, Jeanne Lanvin, Madeleine Vionnet or Elsa Schiaparelli in the birth of modern Style,” explains Julie Blum, director of Galerie Anne-Sophie Duval. “Those amazingly creative minds were the real patrons — even sometimes designers — of the French Art Deco, a new way of life, more feminine, modern and sophisticated.” The first of his apartments to appear in Vogue, rooms were decorated in various shades of white, warm or cold, including “crême de cantal”, a rich, creamy hue, named after the Auvergne cheese, which, in stark contrast to black or dark brown floors, Lagerfeld enthused: “Show off my Art Deco pieces like diamonds in a Cartier showcase.” In the bedroom alone, those pieces included a modernist mirror by André Groult (1884-1996) (brother-in-law of French couturier Paul Poiret (1879-1944)), which hung over a stainless steel bed by Eugène Printz (1889-1948) (covered in a rust red satin the couturier had woven in Lyon), beside which, not exactly your common or garden bedside lamp, stood a monumental bronze and Bakelite torchère, a collaboration between maitre ferronier Edgar Brandt (1880-1960) and Franco-Swiss artist Jean Dunand (1877-1942); opposite, an extraordinary “Shell” sofa and armchairs (c. 1930), from a house decorated by Elsie de Wolfe (1865-1950), their gilt-gold frames offset by ivory satin upholstery, a modernist screen by Eileen Gray in blood-red lacquer (c. 1924) and a pair of monolithic dinanderie vases (1928), each decorated with an abstract motif in black and silver, again by Dunand. Lagerfeld was, in essence, filtering the Jazz Age through a 1970s lens, amping up the glamour for maximum effect, and, as he explained at the time, “It’s more an atmosphere than anything—it is poesie, a dream”.

Seemingly in need of something more contemporary, next he would collaborate with long-time friend, inimitable French decorator Andrée Putman (1925-2013) on apartments in Monte Carlo and Rome. For the former seaside abode, the couturier opted for the colourful and playful design of the Italian Memphis group (an experimental collective of international architects and designers founded by Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007)) whose quaint, kitsch humour and cutting-edge silliness appealed to Lagerfeld’s particular sense of joie de vivre. Typically caustic, Putman described the sitting room, outfitted in candy-coloured furnishings as “like a palace for a child” — an effect added to by Japanese designer Umeda Masanori’s Tawaraya (1981), a boxing-ring-like structure, rather like a giant playpen, intended as a space for conversation and entertainment. Lagerfeld’s Italian aerie, by stark contrast, was predominantly monochrome, decorated in black and white, his chosen colour palette at Chanel, and filled with an array of original Wiener Werkstätte pieces and re-editions of classics by early twentieth-century designers — such as Gray’s Centimetre rug and Fortuny’s cinematic reflector floor lamp. “Each of Karl’s apartments is a perfect and closed universe, but a sincere one,” Putman mused. “His apartments have been a series of successive sincerities. He goes to the end of an obsession for each place: and then he gets rid of stuff.” Subsequently, in Lagerfeld’s decorating trajectory, parallels can perhaps be drawn with fellow couturier and collector Hubert de Givenchy (1927-2018), who, after decorating his Napoleon III apartment on Paris’ rue Fabert, in collaboration with art world darling and decorator Charles Sevigny (b. 1918), juxtaposing a prophetic mix of French court furniture, mirrored walls, leather upholstered steel ottomans and a dazzling array of art by the likes of Rothko (1903-1970), Miró (1893-1983) and Picasso (1881-1973), his taste became increasingly traditional. This can be seen in Givenchy’s famous Salon Vert at the hôtel d’Orrouer, Paris, with its elaborate white and gold decoration by Nicolas Pineau (1684–1754), where a collection of Boulle masterworks formed a powerful ensemble, off-set against dark green silk velvet-lined walls and combined with famille noir, black-glazed Chinese porcelain vases.

Similarly influenced by le grand goût français, Lagerfeld quickly became enamoured by French decorative arts of the eighteenth century, which he came to consider an ideal of elegance and refinement, though, unlike Givenchy, he would take a somewhat more theatrical approach, making no concessions whatsoever to modern day life, an attitude, rather wonderfully described by writer and journalist André Leon Talley (1948-2022) as the couturier’s “Versailles complex”. As such, so as to fully realise his ambitions, Lagerfeld rented an eighteenth-century hôtel particulier at 51 rue de l’Université, which, over the course of thirty years, he would redecorate five times. The couturier’s art de vivre and philosophy of collecting (in a similar way to Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008), who, in 1973, at the age of 12, discovered the work of artist Christian Bérard (1902-1949), which his mother Lucienne later described as “a revelation for Yves”, to the extent that “Theatre was all he could think or talk about”), stem from a pivotal moment when, at the same age as Saint Laurent, Lagerfeld came across a copy of German Realist Adolph Menzel’s (1815-1905) König Friedrichs II. Tafelrunde in Sanssouci 1750 (1850) in a gallery in Hamburg, which marked the beginning of his eighteenth-century obsession. “I didn’t even know if this was French or not,” he said of the work. “But Sans Souci was inspired by Versailles, as were all of the German princes of the eighteenth century.” In Menzel’s depiction of Frederick the Great (1712-1786), sitting at a table with European intellectuals and artists, including Voltaire (1694-1778), Jean-Baptiste de Boyer, Marquis d'Argens (1704-1771) and Count Francesco Algarotti (1712-1764), in a palace he had built for himself, the young Lagerfeld saw a role model for an aspirational way of living. “The beautiful table, sumptuously set, suggested a world that was so different from the strict, nineteenth-century, neoclassical, style that I was surrounded by,” the couturier later explained. “I immediately decided that this refined scene represented life as it deserved to be lived. I saw it as a sort of ideal that, ever since, I have always tried to attain.”

In essence, the intersection of culture, intellect and etiquette depicted in Menzel’s work became a blueprint for Lagerfeld’s entire way of life, his philosophy of collecting, and the basis for the way in which he entertained guests. At rue de l’Université, the couturier surrounded himself with an extraordinary array of decorative arts; in the dining room, a painting depicting a scene from the life of Christ, that once hung the private chapel of Queen Marie de Medici (1575-1642), presided over a suite of gilt-gold, silk upholstered Louis XV chairs and a table draped in white Venetian lace. Meanwhile, in the “grand salon”, against a backdrop of delicate white and gold boiserie panels, in part, executed by Flemish sculptor Jacques Verberckt (1704-1771) (who decorated the apartments of Louis XV (1710-1774) and Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764)), Lagerfeld displayed a collection of fauteuils by an illustrious group of French master menuisiers, including Tilliard (1685-1766), Delanois (1731-1792), and Bauve (died ca. 1786), as well as bronze by Falconet (1716-1791), commissioned by Catherine the Great (1729-1796), depicting two young women as an allegory of “The fountainhead”, atop an extraordinary Savonnerie carpet, that once graced the seventeenth-century Salon de la Paix at Versailles. “The eighteenth century was a most polite century,” Lagerfeld told Vogue fashion writer Kennedy Fraser (b. 1948). “And so modern. It was perfect. The rooms were so flattering to live in. You can age gracefully in them. No one was young; no one was old. Everyone had white hair. Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry wore the same sort of dresses. Age is a racisme that showed up later.” Despite the couturier’s mesmeric passion for all things ancien régime, after three decades he pivoted once more, and in 2000 threw open the neutrally hued doors of his weekend retreat in Biarritz, where, this time, he embraced Geheimrat Architektur, which, in his own words, is “a kind of rich, bourgeois, and intellectual architectural style”. Set in a hundred acres of parkland, a Loro Piana-esque palette of browns and whites predominated, peppered with furniture by Jean-Michel Frank, which Vogue, somewhat tongue in cheek, described as “a study in spare luxury that matches his new physique”.

The Home of Hubert de Givenchy, where, In the petit salon of the hotel d’Orrouer, Picasso’s “Faun With a Spear” (1947) hangs above an antique console © Christie’s images limited, François Halard

Having spent far too many years indulging in sausage-and-Gruyère breakfasts at Café de Flore, the couturier had at the time embarked on a crash course diet, losing 92 pounds in just over a year, with the aim of squeezing into Hedi Slimaine’s (b. 1966) slim-fitting suits for Dior Homme — at the same time, cashing in, by publishing The Karl Lagerfeld Diet (2004) in partnership with chic diet doctor Jean-Claude Houdret (which, if you were wondering, advocated fromage blanc and lobster, provided recipes for “quail flambé” and advised skipping the gym entirely, cautioning, “Exercise runs the risk of making you hungry”). In a similar vein, the house had an outdoor Olympic size swimming pool the health-conscious couturier kept heated to a balmy 31 degrees Celsius, on the pseudo-scientific grounds that: “I put on weight in colder water.” Interestingly, as in fashion, in terms of interiors, the taste of collectors can be cyclical; Givenchy’s last decorative scheme for the courtyard pavilion of the hôtel d’Orrouer was indicative of the direction in which his taste had turned; tiring of tradition, Givenchy embraced minimalism and contemporary works, such as two extraordinary hyper-realistic paintings by Chilean artist Claudio Bravo (1936-2011), which hung either side of a minimalist travertine fireplace. “Modern is modern,” Lagerfeld told Vogue in 1992. “My dream is one day to build a very modern house. I don’t know why, because I have enough houses already, but I dream of it.” That reverie was realised when sixteen years later he embarked on creating a space-age Paris apartment, embracing hyper-contemporary design by figures such as Marc Newson (b. 1963), Martin Szekely (b. 1956) and Ronan (b. 1971) and Erwan Bouroullec (b. 1976). A space as anachronistic as its design-addicted inhabitant, in the couturier’s futuristic boudoir, a pod, delineated by frosted glass walls, the mortuary-like brushed steel bed was, somewhat surprisingly, dressed in the sort of immaculate white linen, lace and crochet one might expect to see in the provincial Palazzo of a conservative octogenarian aristocrat.

Saint Laurent, like Lagerfeld, had a passion for collecting that verged on mania, and as Laurence Benaïm (b. 1961) notes in her biography, “While France thought of itself as ultra-contemporary, in shades of white and orange, Saint Laurent and [his partner, Pierre] Bergé sidestepped the diktats of their peers to rekindle the decorative arts of the 1920s and 30s”. Indeed, since the bespectacled couturier first burst onto the fashion scene in the 1950s, working first for Christian Dior (1905-1957), before launching an eponymous collection in 1962, his inimitable eye for the interplay between the arts, combined with a taste for the theatrical and extravagant, entranced, beguiled and even shocked the fashion press. This can be seen to great effect in the interiors of his many homes, which, again, in a similar vein to Lagerfeld, were created almost as if self-contained “worlds”, each expressing different facets of the couturier’s imagination. Whilst somewhat polarising in their disparate decorating styles, from the nineteenth-century opulence of Château Gabriel in Normandy, a fantastical hommage to Marcel Proust’s (1871-1922) seminal work Á la Recherche du Temps Perdu (1913), to Villa Oasis, the couturier’s private Elysium, hidden within the hustle and bustle of urban Marrakech (a place Saint Laurent affectionately described as, “The city that taught me colour”), each was an expression of individuality, and often, of a culture. However, if one considers the full panoply of the couturier’s many homes, without a shadow of a doubt, it’s the elegant duplex on Paris’ rue de Babylone, the Left Bank “des res” he shared with Bergé, a veritable treasure trove of extraordinary objects, old and new, that most enraptured the public’s attention. “The surfaces were tactile, the colours almost edible and the lighting so flattering. There wasn’t one lamp that if you walked by you didn’t feel absolutely beautiful in its light,” enthuses Marian McEvoy, in her book, The Beautiful Fall – Fashion, Genius and Glorious Excess in 1970s. “The fires were always at the right point, there weren’t too many logs or too few. It was an overwhelmingly sensual interior … Every room smelt of lilies and ivy.” There, against a relatively understated 1920s shell (often wrongly attributed to French decorator Jean-Michel Frank), works by twentieth-century greats such as Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann (1879-1933), Pierre Legrain (1889-1929), and of course, Christian Bérard (the multifaceted French artist whose stage sets so captivated a 13-year old Saint Laurent, that after attending a Bérard-designed production of Molière’s (1622-1673) School for Wives, he wrote to then editor of Paris Vogue, Michel de Brunhoff (1892-1957), “Like Bérard, I would like to devote myself to several things that are in reality one: theatre sets and costumes, decoration and illustration. On top of this, I feel very drawn to fashion”), were juxtaposed against African art, Italian Renaissance bronzes, and whimsical zoomorphic furniture by the couturier’s longtime friends Claude (1925-2019) and François-Xavier Lalanne (1927-2008).

Like Lagerfeld, Saint Laurent was enthralled by the streamlined, yet luxurious aesthetic of French Art Deco, and he acquired some truly breathtaking works, amongst them, Albert Cheuret’s (1884-1966) Console aux trois Cobras (1925), a pair of palm wood and lacquered bronze banquettes (c. 1926), created by Gustave Miklos (1888-1967) for couturier Jacques Doucet’s fabled Studio Saint James, and of course, Irish architect Eileen Gray’s fantastical Fauteuil aux Dragons (1917-1919), which sold in February 2009 at Christie’s Paris for €21,905,000, establishing a record price a piece of twentieth-century design. “Nobody can imagine my capacity for solitude,” Saint Laurent dramatically lamented. “For somebody like me, who can’t stop accumulating objects, the absence of them is an oddity.” Inspired by the decor of collectors Charles (1891-1981) and Marie-Laure de Noailles (1902-1970), the way in which the couturier dared to mix different periods, displaying worlds by Francisco Goya (1746-1828) next to Andy Warhol (1928-1987), Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) alongside Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), Théodore Géricault (1781-1924) near Henri Matisse (1869-1964), and Roman marble with Art Deco furniture, their collection created a unique dialogue between artists and styles. Light years ahead of his time and entirely uninhibited by art world norms, the interiors of rue de Babylone can be compared to a Renaissance Wunderkammer, where, compelled by beauty and quality, as opposed to a rigid, clear-cut approach, what truly unified the collection was the excellence of each and every object; for example, aside from modernist masterworks by the likes of Constantin Brâncuși (1876-1957), Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) and Fernand Léger (1881-1955), among his more unusual acquisitions were a set of silver-mounted necessaire, that once graced the desk of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (1868-1918) and a seventeenth-century Augsburg parcel-gilt ewer and basin by David Beszmann engraved with arms of the Archduke of Austria. “Some people change apartments every three years, I move around objects; it gives them a new life.” In the library, which is where the couturier kept his most personal possessions, coming full circle, one can see framed photographs lining the bookshelves, reminders of friends from earlier days, those such as ballet impresario Rudolf Nureyev (1938-1993), artist Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) and, of course, Chanel. Storied French decorator Jacques Grange (b. 1944) helped Saint Laurent with adjustments and changes to the interior over time, a process which goes some way to explaining why the apartment has proved so enduringly appealing. The couturier’s approach to interiors can best be explained by the way in which he referred to his own career: “I suppose I can say that my success comes from being completely in harmony with my era, I have no nostalgia for the old days. I am glad that things change.” Fashion and interiors have always, and will remain, inextricably linked, especially in a world where image is everything, and where a well-styled public persona can disguise mediocrity and often, even, trump real talent in terms of commercial success. However, as regards the great couturiers, whose originality and exceptional creativity shine through, it might be apt to conclude with the words of Saint Laurent, who considered “elegance is in the heart, in the very being.”