The Extraordinary Mr Chow

The Worlds Most Fashionable restaurateur

“It’s a photograph dress, not a wearing dress. And that reminds me of a story. This man sold a thousand tins of sardines, and the buyer rang him up and said, ‘I’ve just eaten one of your sardines. It was disgusting,’ and this man said, `You fool, they weren’t eating sardines, they were buying and selling sardines.” — Michael Chow on Tina Chow’s Fortuny dress, Vogue, 1973

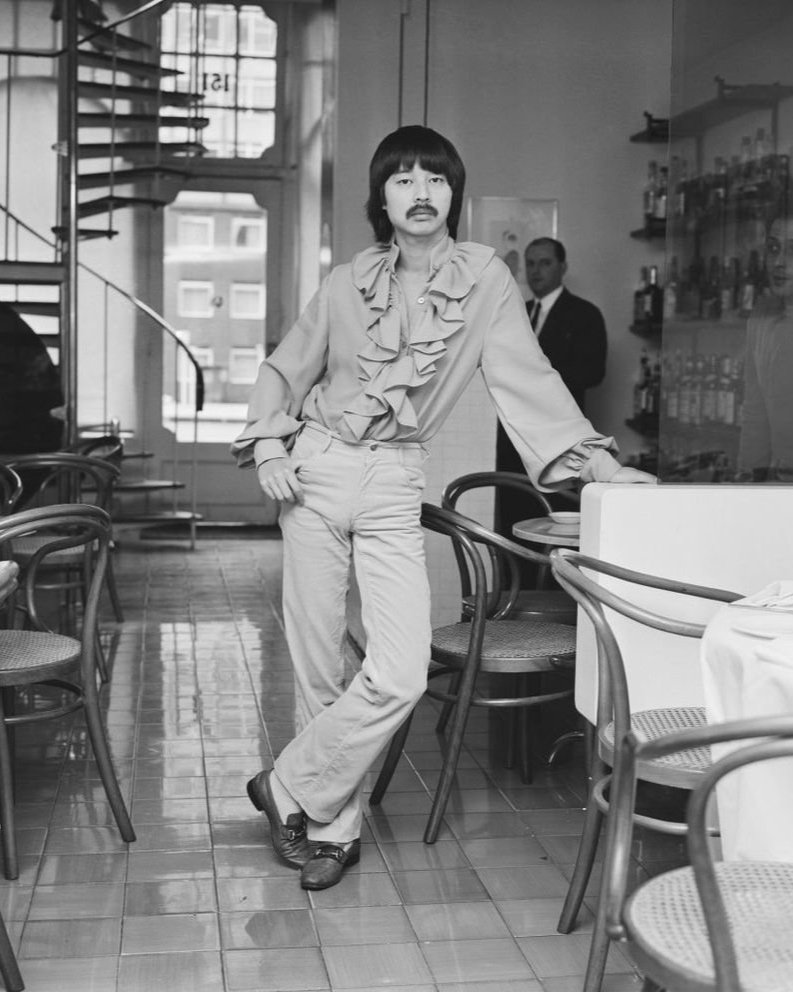

Michael Chow (b. 1939), who these days goes by the single letter moniker “M”, has become something of an iconic figure, as a restaurateur, artist and collector. Like a latter-day, post-modern Marie-Laure de Noailles (1902-1970), Chow operates in a world where “motherfucker”, is employed nonchalantly as a term of endearment, and the creme de la creme of the art world clamour to design chopstick wrappers for his restaurants. With an almost preternatural ability to predict the zeitgeist, Chow sees life as a series of scripted scenes, prewritten and predetermined, played out by those around him, where friends, family and loved ones are willing actors in an aesthetic narrative. “I’m living in the movies all the time,” Chow explains, but, in reference to the kaleidoscopic nature of his endeavours, “Instead of three acts I have five.” To some extent, the Shanghai-born impresario considers films to have been a formative part of his education, stating that each morning, upon waking up, “immediately an image comes to me: Laurence Olivier … in a very important movie for me, Richard III.” This may seem a little esoteric, but there’s method to his Shakespearean madness; in Act 5, scene 3, on the eve of the climactic battle in which the machiavellian warlord meets his grisly end, he’s terrorised by the ghosts of his victims, then in the morning, he’s himself again. “When I have to go to sleep, oh my God, all this shit, all the torture, all my sin. I’ll go through all that,” Chow muses. “But in the morning … I’m Richard.” Interestingly, Chow’s inherently image-conscious approach, in part, stems from his childhood in pre-revolutionary China, which he remembers for its innate decadence, an aesthetic inextricably bound up in brand consciousness — whereby social signifiers of wealth and success, such as Levis 501 jeans, Ray Ban sunglasses and Zippo lighters were all considered de rigueur. Since then Chow’s tastes have become somewhat more refined, perhaps more niche, but still, his affinity for luxury remains strong; considering Charvet socks (long Charvet socks), Hermès suits and bespoke George Cleverley shoes to be the absolute essentials every man must own. The “chicest shoelace”, according to Chow, is from Hermès — one inch thick, made of silk, and one’s butler, apparently, should take it out every morning and iron it. “We can’t get a fucking chicer shoelace,” he proclaims matter-of-factly. Such an attitude, and affection for the finer things in life, can be attributed to a time in the 1960s and 70s, when, as a Chinese immigrant, he carved out a name for himself not only as a global restaurateur but as a “legit and serious” art collector. To be a “somebody” at that place and time, “one has to be eccentric, aristocratic or artistic,” he explains. He went with “eccentric”, creating an instantly recognisable image, sporting shoulder-length hair, ruffled shirts, Saint Laurent suits and Gucci loafers. Of course, his first wife, flame-haired supermodel, and latterly, legendary Vogue editor and stylist Grace Coddington (b. 1941), no doubt made his entrée into the cutthroat world of art and fashion a little easier.

Portrait of Michael Chow (1985) by Jean-Michel Basquiat

Michael Chow and Jean-Michel Basquiat (1984), by Andy Warhol

Born in Zhou Yinghua in Shanghai, Chow’s father, Zhou Xingfang (1895-1975), was a national treasure, and arguably, the most famous man in China; a legendary grandmaster of the Beijing Opera — who went by the stage name Qi Li Tong (Unicorn Child) — he founded the still prominent Qi School of performance. Xingfang’s artistry was an important influence on Chow, who wanted to follow in his on-stage footsteps; from an early age, the aspiring performer was immersed in the highest forms of Chinese culture, which had a deep and profound effect on his aesthetic sensibilities. This idyllic childhood came to a sudden and abrupt end when, on 1 October 1949, the Communist Party led by Mao Zedong (1943-1976) claimed victory over the Nationalists. When government forces began to clamp down on Xingfang’s increasingly nationalistic performances, the then thirteen-year-old Chow was sent away by boat, to study at an English boarding school he later described as “Harry Potter without the magic”. Chow arrived in the darkness of the Great Smog of 1952, completely alone, and would never see or speak to his parents again. The first to be “purged” during the so-called “Cultural Revolution”, his mother, Lilian (1905-1968), the daughter of a Scottish tea merchant, who scandalised society, when she ran off with an older, married performer, was beaten to death by members of the new political regime; his father, arrested and tortured by the Red Guard, died after years of house arrest in 1975. To this day, Chow remembers his father’s poignant parting words of advice: “Wherever you go, always remember you are Chinese.” Small, asthmatic and foreign, Chow had a miserable time at school, finding refuge in cinema, and perfecting a party trick — bringing to mind American mathematician John Nash (1928-2015), as portrayed by Russell Crowe (b. 1964) in A Beautiful Mind (2001) — of memorising, shot for shot, the opening sequence of every classic film from Casablanca (1942) to Breakfast At Tiffany’s (1961).

It’s important to remember, that Chow arrived in the UK at a time very different from that which we now take for granted; the country was still reeling, both economically and mentally, from the aftermath of the Second World War, and, as the restaurateur recalls, “London was still rationing sweets”. It wasn’t until a decade later in 1962, that Britain, for all intents and purposes, went technicolour, with the advent of the Sunday Times Magazine — seen contemporaneously across the industry as a “risky experiment” — which was the first time art or photography could be published in colour for the mass market. Pop art progenitor Peter Blake (b. 1932), now synonymous with the artwork he created for The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band — one of the most infamous record sleeves of all time — was the first to be featured, leading to his enigmatic collages becoming instantly ingrained in the public consciousness. At that point in time, Chow had no way of knowing what a colourful life he would lead. After dropping out of an undergraduate degree in architecture, he trained as a painter at London’s storied Central Saint Martins School of Art. Still unsure of which path to pursue, and keeping his options open, in his early twenties, Chow achieved limited success as an actor, usually in walk-on roles, appearing as a butler in spy-fi comedy Modesty Blaise (1966), as well as the 1967 James Bond film You Only Live Twice, alongside his sister, Tsai Chin, who starred as Ling, one of the film’s obligatory “Bond girls”. In terms of his early artistic career, Chow’s work was well received by his peers and, as part of a group of up-and-coming art stars, he had multiple gallery shows across London — including RBA Young Contemporaries (1957 and 1958), Redfern Gallery (1958) and at the prestigious Institute of Contemporary Arts (1964) (a work from his Redfern show was bought by New York’s Museum of Modern Art) — but, the prejudice he encountered as a Chinese immigrant in London, and the need to earn a decent living precipitated a career change, and as he saw it, society gave him two options: “I say, basically, fuck this, right; so I said, okay, what am I allowed to do, they said, two things you’re allowed to do, laundry or restaurant, which, either one — so I turned restaurant into theatre, you see, that’s what I did.”

Despite, as he called it, “racism and all that”, Chow recognised the “Swinging Sixties” precipitated a cultural sea change, whereby, a period of wealth and prosperity allowed for unprecedented social mobility: “After the war in London, all the young people from different classes went to art school,” the restaurateur recalls, “this was the most liberated revolution, unlike the Chinese one, which was brutal and horrific.” It was during this time of economic opportunity that Mario Cassandro (1920-2011) and Franco Lagattolla (d. 1980), former headwaiters at the Savoy Hotel, changed the face, as well as the taste and collective attitudes of London restaurants. In 1966 they opened Trattoria La Terrazza, or “the Trat”, as it was known, a bijou Soho boîte that perfectly captured the zeitgeist of the 60s — where the likes of Terence Stamp (b. 1938), Peter O’Toole (1932-2013) and supermodel Jean Shrimpton (b. 1942) went to eat Osso Buco, sip espresso and play cards. “It was a tiny little thing with a basement and everyone went there,” Chow recalls. “That was the beginning of the British cultural revolution in the restaurant world.” Alvaro Maccioni (1937-2013) — later described by food critic Fay Maschler (b. 1945) as “the Godfather of many a London trattoria” — started out there as a busboy and later became manager; going on to open his own restaurant, Alvaro’s, in Chelsea, which, as Chow reminisces: “It was the hottest restaurant on the King’s Road, while Mario and Franco were expanding to Mayfair.” Italian food may have been accepted by the haute bohème, but as Deitch recalls, back in 1968, “Chinese cuisine in the West was associated with cheap and noisy restaurants in Chinatown”. Chow set to turn such cliches on their head, opening a restaurant, which was, in essence, a theatre of architecture, art and design. The focus was taken away from the food, which, comprising small plates at fine dining prices — a riff on the sort of nouvelle cuisine so popular in swanky city eateries — can almost be seen as an act of subversion. “Because I lost everything – my parents, my culture, my people – I had an internal desire to appoint myself as a cultural ambassador to promote China. It sounds very corny and cliche, but I did just that.”

Michael Chow inside his London restaurant in 1968, image Evening Standard/Getty Images

"Untitled (Portrait of Michael Chow)" (1984) by Julian Schnabel, with plates from Chow’s restaurant

Prior to opening his now infamous restaurant, Chow had been working part-time for the no less infamous Robert Fraser (1937-1986), the Saville-Row-clad Etonian heroin addict who sold art to Paul McCartney (b. 1942) and hosted John Lennon (1940-1980) and Yoko Ono’s (b. 1933) first joint exhibition in 1968; where they released 365 white balloons over London with a card reading “You Are Here” on one side, and “Write to John Lennon, c/o The Robert Fraser Gallery, 69 Duke Street, London W1” on the reverse (incidentally, McCartney is said to have banged out the rhythm for “Back in the U.S.S.R.”, on a table at Mr. Chow). Fraser’s eponymous gallery was the foci of a “jet set” salon, where Chow mingled with Pop Stars and celebrities, fostering friendships with artists such as Allen Jones (b. 1937), Jim Dine (b. 1935), Patrick Caulfield (1936-2005), Paul Huxley (b. 1938), and Clive Barker (b. 1940). “At that time, there were all these cultural people putting it together and one of the leaders was Robert Fraser, who unfortunately died of Aids,” Chow told Dazed Digital. “We had become very good friends; [He] was like my mentor. He had the greatest deals, the greatest taste, the greatest eye.” Chow was at Alvaro’s on the King’s Road one evening when he saw Fraser at an adjacent table, “I told him about my idea to borrow art and hang it in Mr Chow, and Robert said to me, ‘Why do that? Why don’t you ask some artists to do some work for you?’” Chow approached Blake and asked him to “do the antithesis of racism”, and agreeing, the artist produced Frisco and Lorenzo Wong and Wildman Michael Chow (1966), a collage and mixed media painting depicting the restauranteur in yellow-face, as the menacing manager to the Chinese and Italian wrestlers that flank him; as Blake explains, “a play on the fact that when he opened he had Chinese chefs but Italian waiters”. In terms of the canon of art history, it’s an important piece, as Chow was overtly asking Blake to make reference to the fact that he was Chinese and that in London at the time, in terms of prejudice and outright racism, it was incredibly hard to be Chinese. “It’s very hard to be Chinese today,” Chow muses, “The master hides his weakness, and I’m a grandmaster, I use my weakness, so I use all that shit.” That was the start of Chow’s collection of portraiture, which was somewhat unique, for the simple fact that, as he recalls, “At that time, no artist did portraiture. This was pre-Andy [Warhol], pre-everything. It was very uncool … Only the queen got her portrait done. Those who did portraits were in Siberia, as far as artists go.” Over the years, Chow has become something of a celebrity in his own right, and it’s become almost de rigueur for à la mode artists, from David Hockney (b. 1937) to Warhol (1928-1987) and Urs Fischer (b. 1973) to make his portrait; reproducing the restaurateur’s trademark moustache and impeccably tailored suits (and, in later years, round, black-rimmed glasses) in accordance with their own unique artistic visions. Keith Haring (1958-1990), for example, painted him as a giant, green prawn in a bowl of noodles, which, Chow proffers, “Made me look very ugly, but ugly in art and ugly in life are two different things.”

A close-up detail of one of Chow’s canvases from his solo exhibition, “Bridges”, at London’s Waddington Custot gallery

Opening its doors on Valentine’s Day 1968, Chow’s first venture, slap bang in the middle of London’s affluent Knightsbridge, was, aesthetically speaking, a somewhat eccentric melange, unlike any fine-dining establishment the city had ever seen. Chow’s inspiration for the interiors was the 1946 film Gilda, starring Rita Hayworth (1918-1987), and upon opening, an eclectic crowd of art, fashion and various other creatives were taken aback by the restaurant’s luminous white room, with vaulted ceilings, verdant green floor tiles, elegant Art Deco furniture and white-jacketed Italian waiters. Whereas Chow commissioned Blake to produce a work that was the “antithesis of racism”, American film-maker Nick Hooker, who produced the recent feature-length documentary AKA Mr Chow (2023) goes as far as saying “It was an anti-racist restaurant”, where the diners, many of them not white, were the stars. As a result of Chow’s ingenious, and early, cross-pollination of food, art and society, his debut eatery became the gallery world’s go-to for opening night exhibition celebrations, and in turn, a bonafide cultural institution. “Every artistic generation has been part of the scene at Mr Chow,” Deitch writes. “Indeed, more connections have been made there than in most art galleries.” Over the next half-century, Chow developed close personal relationships with a veritable who’s who of art world behemoths, including Andy Warhol (1928-1987), Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Julian Schnabel (b. 1951) and Keith Haring (1958-1990). American artist Ed Ruscha (b. 1937) made Mr Chow LA (1973), where the “recipe” for colours is listed as egg yolk, oyster sauce, red cabbage, soybean paste, red bean paste over coconut milk, red beet, and “secret ingredients”. Originally, Chow made the somewhat unusual request that the artist baste the background of the canvas in soy sauce. After months of waiting, the frustrated restaurateur lost patience and called the artist at his studio. As Chow remembers it, “Ed, with a melancholy voice, said, ‘Soy sauce just won’t dry.’ Hence, an important scientific discovery was made: soy sauce never dries.” In its place, Ruscha used egg yolk for the ground and painted the letters of the title with “an assortment of delicious vegetables. The picture is good enough to eat,” Chow writes.

A truly immersive experience, original art extends beyond the walls of his restaurants; crockery features a logo by American artist Cy Twombly (1928-2011) — “Yeah. You can’t get chicer than that,” Chow muses. “Apart from maybe the Queen.” — Andy Warhol designed the chopstick wrappers and a 1969 portrait of the restauranteur by David Hockney adorns the matchboxes. “Look at our menus, the handmade paper. The Helmut Newton image. I sat for Helmut, how many times? Eleven times. All over the world. So on one side you have Helmut and on the others you either have the David Hockney portrait of me or Ed Ruscha. So, again, very chic.” (Across the back of Chow’s portrait Newton scrawled: “You stick to the noodles and I take the snaps! Love Helmut.”) Then there’s the restaurant’s guest book, or, as Chow tellingly refers to it, the “artist’s book”, which, as he’s at pains to point out, is, in fact, a specially commissioned tome, “with very good paper”, containing impromptu works by a slew of artistic luminaries, a veritable who’s who of Modern Masters, including Francesco Clemente (b. 1952), Jasper Johns (b. 1930), Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997) and Francis Bacon (1909-1992) — “everyone except Picasso,” the restaurateur proffers wryly. “Of course, once they see who was in it, they are competing with everyone, Warhol, being very naughty, made a waterfall out of chilli sauce, which bleached other people’s work. It was kind of terrorism,” Chow laughs. “So this book is amazing — it is a documentary of the second part of the twentieth century. People like David Salle drawing the hand of William Rubin, who was the head of the Museum of Modern Art, holding a cigar.”

When Chow arrived in New York, to open his restaurant on East 57th Street, Ian Schrager (b. 1946) and Steve Rubell (1943-1989) threw him a Peking-themed birthday party at Studio 54; the pair had recently been arrested for tax evasion and skimming $2.5 million off the books — and as everyone in the city knew, it was to be the last great part thrown at their iconic Manhattan nightclub; a thousand people were invited and hundreds more clamoured outside, desperate to get into the party, where a troupe of performers, including fortune tellers and jugglers, entertained Chow’s glamorous VIP guests. “When we opened the restaurant, the phone never stopped ringing — it had to be taken off the hook,” Chow recalls. “Jean-Michel Basquiat came by and gave me a painting. Then Julian Schnabel came to the restaurant and wanted to meet me.” Deitch first dined at Chow’s New York outpost in 1984, at a Mary Boone (b. 1952) fête for Basquiat’s upcoming solo show at her 420 West Broadway gallery. “It was like a reverse stage,” he writes. “From the bar one could look down on the glamorous crowd, and the crowd below could look up at the luminaries seated at the prestigious mezzanine table.” Chow went on to open restaurants in Los Angeles County (Beverly Hills and Malibu), Miami and Las Vegas. Better known for their star-studded clientele, than rave reviews, Chow’s string of high-end eateries drew in a revolving door of A-list celebrities, such as Mick (b. 1943) and Bianca Jagger (b. 1945), Gregory Peck (1916-2003), Lana Turner (1921-1995) and Groucho Marx (1890-1977) (who didn’t eat Chinese food, and instead, ordered in hamburgers). Chow’s fondest memory is of Hollywood legend Mae West (1893-1980) turning up, unannounced, at his elegantly appointed LA outpost: “The whole room stood up and applauded.” Its eclectic menagerie of patrons didn’t dine there because they wanted a quiet meal — they hoped to be in the same room as Jack Nicholson (b. 1937) or Tina Brown (b. 1953) — to be part of the theatre Chow had created. Such was its inherent mystique that even art world kingpins such as Basquiat, Ruscha and Dine offered art in exchange for generous food and drink tabs. Hooker recalls the first time he set foot in Mr Chow in London in the late 1970s: “My parents were separated, and I think there was a bit of ‘I’m gonna make sure he has a great time,’” he recalled of the excursion that became a father-son tradition. “We’d go to Mr Chow and have lunch and then we would go watch a James Bond double bill. Whenever I walked in there, something happened. The chemistry in my body kind of changed.”

After years spent hobnobbing with the crème de la crème of the art world, at eighty years old, Chow returned, after five decades, to a long-shelved dream and started making art himself. It was Deitch, then Director of MOCA, Los Angeles, who reignited the restaurateur’s passion for painting; after visiting Chow’s capacious gallery-like Hollywood Hills home in 2011, the curator complimented a piece that turned out to be one of Chow’s early 1960s abstractions. “I knew that he came from an artistic background,” Deitch explains, “but I didn’t know that he was a very serious painter. There is this energy and drive of a young artist, but also this wisdom and experience of a mature man.” Picking up where he left off when his restaurant exploded, Chow acquired a sixty thousand-square-foot studio in California, where he works for up to ten hours a day, creating monumental canvases, incorporating a multitude of found materials, such as leaves, footballs, string, silver and gold leaf. Obvious comparisons can be drawn with the Abstract Expressionists and Colour-Field painters of the 1950s New York School, as well as traditional Chinese ink painting and calligraphy; references which, in essence, have been familiar to Chow his entire life.

Michael Chow painting in his Los Angeles studio, a process at once cathartic and physically demanding, image c/o HBO

Indeed discussing his use of unexpected, and found materials, Chow makes direct reference to Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), who put cigarette butts in his paintings, explaining that he’s doing the exact same thing. The key difference is that, whereas artists like Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), Franz Kline (1910-1962), and Mark Rothko (1903-1970) were dealing with flat planes, Chow’s work is incredibly sculptural, and as Jacob Twyford, senior director at London’s Waddington Custot gallery explains, “It’s sort of twenty-first century abstract expressionism, rather than twentieth century”. Chow’s process is at once cathartic and physically demanding, expressing himself through explosive gestures; for example, hammering paint across paper, burning plastic and smashing eggs onto a canvas. In many ways, his work is a process of deep, personal exploration, coming to terms with the trauma of his childhood. As Chow explains, “In collaging, you can put things together that shouldn’t be together, and that’s my life.” Last year, he had his first UK solo exhibition in nearly sixty years, Bridges, at Waddington Custot; where six large-scale canvases were displayed alongside a number of “One Breath” works on paper; a nod to the traditional art of one breath calligraphy, whereby he takes a hammer to a deep pool of paint, creating an immediate, explosive expression, with no room for revision. “Painting was the magic carpet out of his depression,” Hooker told the Guardian. “When he started painting again, he suddenly rediscovered his enthusiasm for being alive.” As an artist, one sees beyond the showman, with works that are an expression of his true self, divorced from the superficial trappings of fame, fortune and celebrity. “[For] the real version of me, look into my painting, Painting can never lie. Nowhere to go, nowhere to hide. We will find you.”

It was Schnabel, as well as Deitsch, who first encouraged Chow to once again pick up his paintbrushes, and of their intense and enduring friendship the restaurateur enthuses: “He has supported me all this time, he’s such a passionate man. We did everything except sex.” In 2015, Schnabel flew from New York to Miami for a party during Art Basel, to mark Chow’s upcoming exhibition, “Voice for My Father”, at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. (Which coincided with a Chinese celebration of what would have been Zhou Xingfang’s 120th birthday: “In China, my father is like Shakespeare.”) An eclectic assemblage of deep-pocketed potentates, art, fashion and cultural luminaries were in attendance, including Bret Easton Ellis (b. 1964), Sir Norman Rosenthal (b. 1944), Sydney Picasso, Simon de Pury (b. 1951), Mario Testino (b. 1954), Stefano Tonchi (b. 1959) and Guy Laliberté (b. 1959). Dom Perignon was flowing, the food barely there and Christmas music was blasting through the speakers, which, apparently, Chow explained, was a result of his wanting the “happiest music possible”, so as to provide contrast to an atonal Chinese opera, to be performed later in the evening, in honour of his late father. “It will be a completely strange sound, and this is the sugar you are getting before,” he said in reference to upbeat seasonal medleys such as Mariah Carey’s (b. 1969) All I Want for Christmas is You. “It’s a touch of genius if I would say so!” Shortly before the performance, Schnabel, mic’d for the crowd, hopped up on stage, yelling at an iPhone, explaining he was trying to find an e-mail containing a paean to Chow’s paintings, penned by a man whose name had seemingly escaped him — “He’s a writer, he was very smart, he wrote a book about Proust” — while staying at his home, the Pompeii-red Palazzo Chupi in New York. The assembled crowd, entirely uninterested in what, presumably, the artist intended as a tender moment of tribute to his long-time friend, continued, wholly oblivious, in their champagne-fuelled small talk. Finally losing his patience, “Girls and boys,” the disgruntled artist screamed, gesturing at a group of revellers, including Paris Hilton (b. 1981), Julian Lennon (b. 1963), Dylan Brant, Rose McGowan (b. 1973), Amanda Hearst (b. 1984), and “Baby” Jane Holzer (b. 1940). “Shut the fuck up, please!”

“The biggest misunderstanding is thinking a restaurant is like a bank. It’s not like a bank, it’s like a musical. The curtain goes up and you start singing,” Chow proffers. “Rule number one of the theatre is never bore the audience.” Of course, the success of Mr Chow has much to do with its mingling of food, art and high society across three continents for over five decades; making it a hotspot for creative luminaries from Warhol to Janet Jackson (b. 1966), becoming the last word in “scene cuisine”, and, as fashion writer Horacio Silva puts it: “The champagne-fueled place for the bon ton to go for a wonton”. Chow famously installed a periscope with a video camera in the ceiling of his restaurant, so as to watch the show from his office; and it seems as yet, the curtain is nowhere near falling on what has recently been dubbed the “Chow Dynasty”. In recent years, a newly minted generation of pop culture parvenues have discovered the enduring magic of Mr Chow — Kim Kardashian (b. 1980) and Lady Gaga (b. 1986) are both said to be fans, as is LA-based multimedia artist Alex Israel (b. 1982). Indeed its pop cultural appeal never seems to diminish, with rap mogul and music entrepreneur Jay-Z (b. 1969), contemplating the nihilism of wealth and fame — and the eternal question of just how much fine dining one man can stomach — calling out Mr Chow, with his own unique lyricism, on his smash hit Success: “How many times can I go to Mr Chow’s, Tao’s, Nobu? Hold up, let me move my bowels.” Chow was prescient in anticipating the convergence of the culture and lifestyle industries, as the rise of ready to wear, and in turn, the democratisation of fashion, made fame and glamour seem more accessible to a newly minted haute bourgeoisie. In Deitch’s essay, The Restaurant as a Total Work of Art (2018) he describes Mr Chow as “an immersive aesthetic experience, fusing art, architecture, performance, and culinary innovation,” which, in part, is down to Chow’s extraordinary eye for detail: “I find the perfect thing, and I’ll never let it go, like that song in ‘The Sound of Music’. I find the perfect ice bucket, and I never let it go. And the perfect hinge, perfect chair, perfect table.” In a rare moment of candour, Chow tells Hooker in his recent documentary: “The problem with racism it hurts, you take away my glasses and take away my Rolls Royce, I’m not good enough now.” Having started with Richard III, to paraphrase Shakespeare’s Hamlet: therein lies the rub. “Everybody thinks I’m not an artist. Some of them think of me as a chop suey man or whatever, but at the end of the day, I’m an artist.”