House of Glass

“For architects [Maison de Verre] represents the road not taken: a lyrical machine whose theatricality is the antithesis of the dry functionalist aesthetic that reigned through much of the 20th century” —Nicolai Ouroussoff

Though not quite a household name like his friends Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) and Max Ernst (1891-1976), Pierre Chareau (1883-1950) is internationally recognised as one of France’s first truly modern architects; cited by Richard Rogers (b. 1933) and Jean Nouvel (b. 1945) as a major influence on their work. Straddling the divide between tradition and modernity, Chareau is best remembered for his extraordinary Maison de Verre (1932) which he designed in collaboration with Dutch architect Bernard Bijvoet and craftsman metalworker Louis Dalbet for the physician Jean Dalsace and his wife, Annie. Maison de Verre epitomises the principles of his work: formal invention, the use of the finest materials and transformable spaces and furniture created by the best artisans. “[Chareau] applied his gifts of invention to think through the residence—not to decorate it, but to organize it as a function of the inhabitant,” explained Chareau’s friend, Francis Jourdain, “to take into account the resident’s material needs without ignoring the spiritual ones.”

Chareau was born in Bordeaux, France, to Esther Carvallo and Adolphe Chareau. His father was a wine merchant who lost his fortune and moved to Paris to work on the railroad. After failing his entrance exam at the eminent École des Beaux-Arts, Chareau took a job at Waring and Gillow, a British furnishings company based in Paris, rising from an apprentice to head designer. It was during his years as an intern that Chareau learned about the different types of wood, their functions and attributes, and their pairing with metals. After serving in the French artillery corps, upon his discharge in 1919, Chareau established his own studio. The influence of avant-garde movements such as Neoplasticism, Cubism and the Dutch group De Stij can be seen in his bold experiments with materials like glass, steel, and light itself: “In my opinion, the modern movement is but a perceptible moment in a continuous creative process,” he wrote, “whose origins can be traced back to the oldest forms of human knowledge.”

Chareau in his Paris apartment at 54 Rue Nollet, on the wall behind him are works by Picasso and Lipchitz (c. 1927), photograph by Thérèse Bonney

Maison de Verre, Paris (1932) by Pierre Chareau

One of the first projects Chareau completed, a design of a study/bedroom for his friend, Jean Dalsace, was exhibited by the annual Salon d'Automne show in Paris. This spurred him on to create more avant-garde furniture, lighting and architectural designs for the haute bourgeoisie of interwar Paris, including leading figures of the intelligentsia. Adopting a modernist approach to his furniture, Chareau balanced the opulence of traditional French decorative arts with designs that were elegant, functional, and in sync with the requirements of modern life. His furniture, characterized by the innovative use of exotic woods and forged metal (executed by the ironsmith Louis Dalbet), often incorporating ingeniously devised kinetic components, intended to be rearranged according to the preferences of its user. This was something that appealed to the sensibilities of his more progressive patrons, who felt the social pressures of a new age which called for simpler and more affordable furniture.

Chareau soon joined the prestigious Société des Artistes Décorateurs, which included Maurice Dufrène (1876-1955), René Herbst (1891-1982), and André Groult (1884-1966). In the mid-1920s Chareau opened two Parisian retail locations: a shop on the Left Bank, where he sold cushions and hand-throws, and a showroom on the Right Bank, which carried his furniture and lighting designs. With a profound passion for creating new and diverse environments, not only individual furnishings, Chareau began work as a scenographer in 1924, collaborating with modernist architect Robert Mallet-Stevens to create furniture for director Marcel L’Herbier. His first major success as a designer came in 1925, when he created an “Office-Library in the French Embassy” for the Pavillion de la Société des Artistes Décorateurs. The circular room boasted a domed roof with a system of adjustable wood panels filtering light from above. Shown at the revered Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, it contributed to Chareau's growing reputation as a key figure in twentieth-century decorative arts.

Under construction, Maison de Verre, Paris (1932) by Pierre Chareau

The Maison de Verre (or “Glass House”) was completed in 1932, just as the effects of the 1929 crash were being felt in France. The affluent classes — who during the golden age had commissioned entire suites — were no longer capable of supporting their former lavish lifestyles. Many of the the artistes décorateurs were forced to change direction, pushed towards metal, in the hopes of mass-producing their designs. French furniture makers, unlike the Germans, were not interested in mass-production; thus, the avant-garde designs of Le Corbusier (1887-1965), Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) and Pierre Jeanneret (1896-1967), not to mention Chareau's own metal furniture, although less expensive than furniture veneered in precious woods, remained luxurious, tied to the high-quality, labor-intensive craftsmanship that had set French decorative arts apart since the eighteenth century. To this end, in Maison de Verre, the sofas have tapestry seats designed by Jean Lurçat (1892-1966), likely executed by one of the storied French tapestry manufacturers such as Aubusson or Gobelins: “the very idea of uniformity is odious to me,” Chareau wrote. “One may desire its advent, but submitting to its tyranny is repugnant.”

Whilst creating precious, hand-crafted furniture for distinguished clients, Chareau was also a modernist working in the same time and place as Le Corbusier, who declared that “A house is a machine for living in,” a statement which certainly applies to the Maison de Verre. The external form, in glass and steel, had to be carved out of an existing 18th-century hôtel particulier. Jean bought the pre-existing building towards the late 20’s, planning to demolish the structure in its entirely, so as to realize Chareau’s project, but much to his chagrin, the elderly tenant on the third floor of the building, in accordance with a Parisian tenant law, absolutely refused to quit her lodging. Chareau was forced to carve the new construction out of the space beneath. The bottom floors were removed and with the use of steel columns and beams the floors above were propped up so as to remain in place. For this reason, the last floor of the building still features a completely different style.

“He set out to create a space like a musical composition, which would accommodate the practice of a pioneering young doctor, the art of family life, and the entertaining of friends” —Dominique Vellay

Maison de Verre can be seen as a reflection of Chareau’s idea of the architectural machine-edifice. In one of the first articles on the house in L’Archictecture d’aujourd’hui, Chareau described it as a “model made by artisans with a view towards standardization”. The façade of the building consists of translucent glass blocks in a steel grid, with select areas of clear glazing for transparency. Internally, instead of masonry walls, spatial division could be continuously modified by the use of sliding, folding or rotating screens in glass, sheet or perforated metal, or in combination. The house is full of ingenious mechanical components, executed by Louis Dalbet, like an overhead trolley from the kitchen to dining room, a narow retractable ship’s stair that links the petit salon to Mme Dalsace's boudoir and windows that opened and closed using a system of counterbalances. Interestingly, much of this intricate moving scenery —stairs, cupboards, windows and walls, that swivel out, pivot and slide — was designed on site as the project developed. This was an attempt by Chareau to create a new kind of “machine for living”, in sync with the vicissitudes of modern life.

The program of the house was somewhat unusual, in that it included a ground-floor medical suite for Jean Dalsace; so as to accommodate for the client, Chareau created a studio to welcome patients on the ground floor. This variable circulation pattern was provided for by a rotating screen: during the day it hides the private stairs from patients, thus preserving the home’s privacy, and in the evening it acts as a decorative frame. “No house in France better reflects the magical promise of 20th-century architecture than the Maison de Verre,” then architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote in an August 2007 New York Times article.

Maison de Verre, Paris (1932) by Pierre Chareau

Even prior to the commission of the Maison de Verre, Chareau and his wife, Louise Dyte (Dollie), were active patrons of the arts; known to have the works of Paul Klee (1879-1940), Juan Gris (1887-1927), Braque (1882-1963), Picasso (1881-1973), Chagall (1887-1985), Max Ersnt (1891-1976), Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1975) and Modigliani, hanging on the walls of their apartment. As forward-thinking in their taste for art, music, theater, and film as they were in their politics; they hosted concerts, avant-garde film projections and poetry readings for the celebrated artists, writers and musicians of the day. Once complete, the Maison de Verre’s double-height “salle de séjour” was transformed into a salon regularly frequented by Marxist intellectuals like Walter Benjamin as well as by Surrealist poets and artists such Jean Cocteau (1889-1963), Yves Tanguy (1900-1955), Joan Miró (1893-1983) and Max Jacob (1876-1944). According to the American art historian Maria Gough, the Maison de Verre had a powerful influence on Benjamin, especially on his constructivist — rather than expressionist — reading of Paul Scheerbart‘s utopian project for a future “culture of glass”, for a “new glass environment [which] will completely transform mankind,” as the latter expressed it in his 1914 treatise Glass Architecture.

Forced to flee France when the Nazis occupied Paris, Chareau and his wife migrated to Marseilles, then Morocco, and finally New York, where he arrived penniless and unknown. In 1946, he designed a house and studio in East Hampton for the Abstract Expressionist artist Robert Motherwell (1915-1991). Radical for its time, the Motherwell House and studio were built using surplus Quonset huts, utilizing low cost materials like an industrial greenhouse window, concrete blocks for the retaining walls, plywood, brick and oak logs for the floor. The house gained some notoriety when it was photographed for Harper’s Bazaar in June of 1948; but unfortunately, bad press for the project led to a decline in work for the designer. The Motherwell House (callously demolished in 1985) was Chareau’s only important project outside of France.

The Chareau’s survived partly on what money his wife could earn giving cooking lessons to wealthy Americans and from selling off art from their collection, including a precious Amedeo Modigliani sculpture to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Chareau spent the final years of his life in exile and relative obscurity; in the 1950s, in an attempt to resurrect his reputation, he reached out to the director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris. Around the same time he began negotiating with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) about a possible New York show of his work.

The Paris show never materialized, and Philip Johnson, MoMA’s mercurial director of architecture — a staunch supporter of Chareau’s rival Le Corbusier — vetoed the idea; perhaps because he had just completed his own Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut. Downtrodden, Chareau died later that year. For an all-too-brief period, spanning only a dozen years, Chareau’s oeuvre represented the magical promise of twentieth century architecture; it would take another generation for his prominence to return, his work having a profound impact on a generation of architects who were seeking to free themselves from the rigid orthodoxies of mainstream Modernism.

“[Francis] Jourdain said that he once had a dream in which he was watching one of the old fashioned French elevators of wood and glass going up and down. Inside the elevator was a wood-burning stove with a stovepipe attached, which extended and contracted like a telescope as the elevator went up and down,” Brian Taylor recounts in Pierre Chareau: Designer and Architect (1992). “When Jourdain awoke from his dream, the first name that came to his mind as the inventor of such a machine was that of Pierre Chareau!”

Ben Weaver

Petit Salon with retractable stair leading to Mme Dalsace's boudoir, Maison de Verre, Paris (1932) by Pierre Chareau

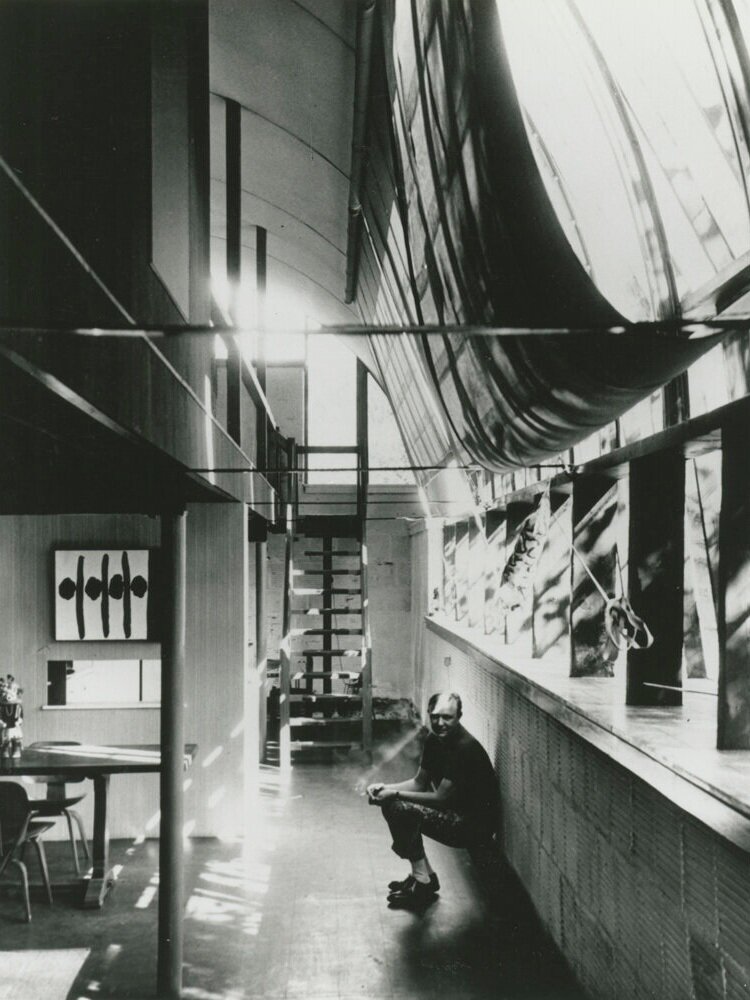

Interior of the Motherwell House, East Hampton (1946) by Pierre Chareau