The Art of Living

Charlotte Perriand

“It's not about today that we need to be thinking; it's about tomorrow. There is of course the need to make inexpensive products. New models have to be created for the masses. But I think there is also something beyond pret-a-porter. Say we no longer use techniques like weaving because of the expense. So do we do without it definitively? Why? There's no need. What is inexpensive because it is produced cheaply won't last … But when I talk to you about tomorrow — it will have to cost nothing, be made with new materials and new techniques. It will, of necessity, be made of things as they are.” — Charlotte Perriand

Along with Jean Prouvé, Jacques Adnet and Jean Royère, French architect and furniture designer Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) embodied l’esprit nouveau. A visionary and innovator, she was a member of that avant-garde cultural movement which, from the first decades of the twentieth century, brought about a profound change in the rituals of daily life with new aesthetic values. “Living means moving forward” Perriand used to say. “You have to give voice to your era”. With an oeuvre encompassing Art Deco, the machine aesthetic, organicism, biomorphism, Art Brut and industrial prefabrication, Perriand is deemed to be one of the most important designers of the mid-20th century. Preferring to be known as an “interior architect”, and not as a furniture designer, she believed in the modernist notion of “form follows function”, and that furnishings and architecture needed to be developed in tandem, as a single entity, to create a cohesive, visually stimulating whole. In her article L'Art de Vivre (the art of living) (1981) she states: “The extension of the art of dwelling is the art of living — living in harmony with man's deepest drives and with his adopted or fabricated environment.”

In an extensive and prolific professional career spanning eight decades, Perriand created a wealth of influential design pieces, including chaise lounges, armchairs, and tubular “equipment for living”, bamboo furniture in Japan, lobbies for Air France in London and Tokyo, workers' housing in the Sahara and ski resort interiors in the French Alps. Perriand shared Lefebvre’s humanist, Marxist vision of equality, proselytising about how good design should be fundamentally transformative and accessible to all; she favoured flexible space, free-form shapes, natural materials, and functional design to “make the space sing”. Born to a tailor and an haute couture seamstress, Perriand studied furniture design under Maurice Dufrêne at the École de l'Union Centrale des art Décoratifs from 1920-1925. On completing her studies, believing that she had nowhere to go but to the top — as she told Roger Aujame, a friend and former Corbusier Foundation director — she applied to work in the hallowed studio of architect Le Corbusier: “The austere office was somewhat intimidating, and his greeting rather frosty,” Perriand wrote in her memoirs. “‘What do you want?’ he asked, his eyes hooded by glasses. ‘To work with you.’ He glanced quickly through my drawings. ‘We don’t embroider cushions here,’ he replied, and showed me the door.”

Charlotte Perriand in January 1991

Air France travel bureau, London, designed by Perriand and Thomas and Peter H Braddock, 1950

Yet two years later, in 1927, Perriand’s Bar Sous le Toit, or Bar Under the Roof, created a succès de scandale at the prestigious Salon d’Automne, establishing her as an avant-garde talent to watch. Attracting attention for its striking modernity, the ensemble of furnishings re-created a section of her own tiny attic apartment on place Saint-Sulpice. Stools with tubular metal legs, clustered around a curvaceous cocktail bar; the gleaming aluminium and nickel-plated surfaces, contrasting with colourful leather seats, are evocative of the dynamic, sensuous forms of stylish automobiles. As Perriand later recalled: “The upright Salon hadn’t expected its galleries to bubble with such brazen youth.” Perriand’s work embodied Le Corbusier’s belief in furniture which serves as “extensions of our limbs and adapted to human functions that are: Type-needs, type-functions, therefore type-objects and type-furniture.” So impressed was he by her bar installation that he immediately invited her to join his studio, beginning a decade long collaboration. As Perriand said in 1984: “I think the reason Le Corbusier took me on was because he thought I could carry through ideas. I was familiar with current technology, I knew how to use it and, what is more, I had ideas about the uses it could be put to.”

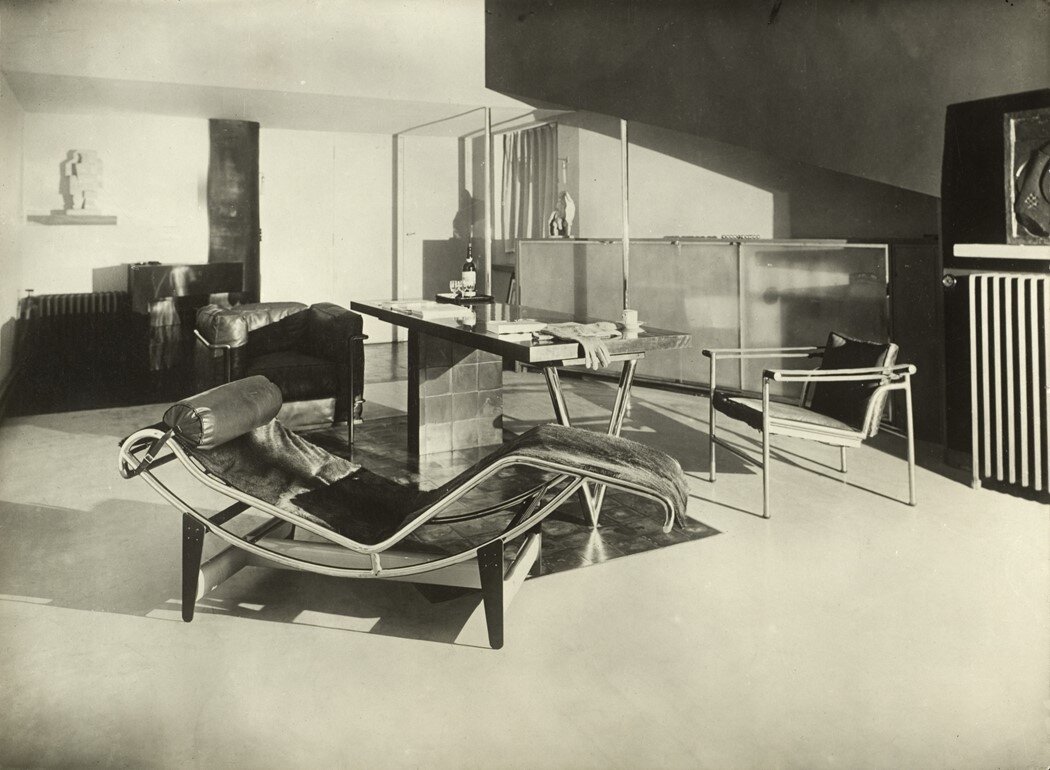

Le Corbusier tasked Perriand with designing l’équipement intérieur (furniture and fittings), something for which had little patience or aptitude: “Le Corbusier always interested himself in the ‘why’ of things,” Perriand explained in a 1984 interview for Architectural Review. “[He] had no time for what he called ‘le blah blah blah’”. Based on sketch analysis of Le Corbusier’s “seven states of sitting”, Perriand devised a series of tubular steel chairs, among them the B301 sling back chair, LC2 Grand Comfort, and the adjustable B306 Chaise Longue (a “machine for relaxing”). “Ils sont coquets”, was her employer’s approving reaction. Derived from precedents such as bentwood lounge chairs and adjustable seats for invalids, Perriand’s chaise longue has become a synecdoche for Modernism: “We have built it with bicycle frame tubes and we covered it with a magnificent pony skin”, Le Corbusier asserted. “It is so light that it can be pushed with the foot, it can be moved by a child.” Credited to the studio of Le Corbusier and branded with the LC Collection moniker, these ergonomically designed, minimalist masterworks are revered as 20th century design classics.

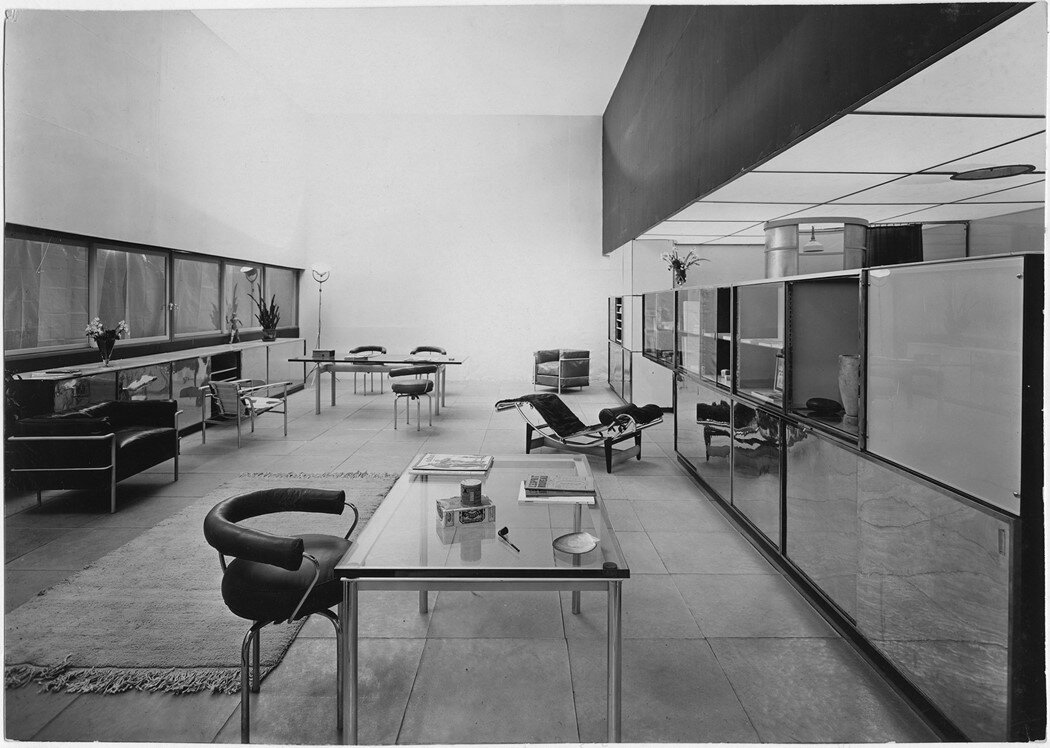

Two years later Perriand, along with Jeanneret and Le Corbusier, presented and installation entitled Un equipement interieur d’une habitation at the 1929 Salon d’Automne; described by Max Terrier in Art et Decoration “as a manifesto, a proclamation, a declaration against the bourgeois ideal of the upholstered living room”. The spectacular single-room apartment, which exchanged walls for functional partitions was a masterclass in open plan living and the radical use of space. Perriand had created a modernist interior in the spirit of gesamtkunstwerk (a “total work of art”), in which all of the interior elements conformed to the same aesthetic function and principles. It was the same year in which Eileen Gray completed the experimental Villa E-1027 on the Côte d'Azur, and Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe presented his Pavilion of the German Reich with the iconic Barcelona chair at the International Exposition in the same city. Unlike Gray and Van der Rohe, Perriand was the only one who focused on standardized architectural components for mass production; thus adding a distinct dimension of humaneness to the often cold rationalism of Le Corbusier. Perriand believed that art should be enjoyed as part of daily life, and to that end, through her creations, she managed to make it both easier and more beautiful, imbuing humanistic aspects into her designs. For Perriand, there was no prescribed method or style: neither metal nor wood, industry nor craft should dominate, she said, because “we use each in its practical place”.

Desk for the office of Jean-Richard Bloch (1938), designed by Perriand © Archives Charlotte Perriand

Perriand’s work continued to evolve, and in the 1930s, she developed an interest in natural materials such as wood and cane. Participating in the intellectual circles of the Communist Party, where she met Miró, Picasso, André Malraux and Blaise Cendrars, she became increasingly radicalised; in response to the decade’s cascade of political and economic crises, her focus became more egalitarian and populist. She developed cheaper designs, intended to be replicated or mass-produced, and actively critiqued and campaigned against the way in which contemporary architecture failed to address adequately questions of basic social need. Perriand helped to found the Union des Artistes Modernes (UAM), and in 1933 she embarked on a photographic research project in collaboration with Fernand Léger and Pierre Jeanneret, collecting “pebbles, bits of shoes, lumps of wood riddled with holes, horsehair brushes – all smoothed and ennobled by the sea … We called it our art brut.” In 1934 she began specialising in low-cost, high-design, pre-fabricated buildings for leisure pursuits, including the Maison au Bord de l'Eau (“House on the Water”), as well as hotels and mountain shelters.

Perriand left Le Corbusier’s studio in 1937 to work on a ski resort in Savoie and a stand for the 1937 Paris Exhibition. In 1938, when she was commissioned to design a desk for the office of Jean-Richard Bloch, editor of left-wing newspaper Ce Soir, she conceived a “free form” boomerang shape that encouraged dialogue with journalists, also designing a coffee table whose top integrated two abstract drawings by Fernand Léger (Tyrecap and Fragment of glazing) and engravings by Picasso from his satirical series Songe et Mensonge de Franco (Dream and Lie of Franco). In 1946, Perriand made her first journey to Japan to work as an official advisor for industrial design to the Ministry for Trade and Industry. Her role was to advise the government on how traditional Japanese crafts could be improved for export to the west.

Only two years in, at the height of the Second World War, Perriand was expelled as an “undesirable alien”. Wartime naval blockades made it impossible for her to return to France, and she was forced to remain in the then-French colony of Indochina — which included Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam — until the end of the conflict. There she met Jacques Martin, a French government official, whom she married in in 1943. Following her time in Asia, Perriand’s designs began to show influence of her time spent there, notably in the Vietnamese woodworking and weaving techniques and the Japanese use of natural materials and usage of screens as a method to divide spaces. “I like being alone when I visit a country or historic site,” she explains in her autobiography Charlotte Perriand: A Life of Creation. “I like being bathed in it's atmosphere, feeling in direct contact with the place without the intrusion of a third party.”

Perriand returned to Paris in 1946, accompanied by a new husband and their toddler daughter, Pernette. Fiercely independent, Perriand rejected frequent requests to furnish buildings designed by other architects. She developed a new concept for the way of living, in part influenced by her pro-communist political involvement, by increasingly integrating the human dimension into her productions; through a flexible use of materials and her intimate connection with nature, she achieved recognition through her pure and powerful style – as exemplified in her free form massive wood table models. “Always concerned with innovation rather than trying to affirm a formula for renovation”, Perriand was determined to turn her hand to low-cost furniture for mass production, and to finding a synthesis between tradition and industry.

Again she approached Le Corbusier, who was working on the Unité d’Habitation housing project in Marseille. “I do not think it would be interesting, now that you’re a mother … to oblige you to be present in the atelier,” he wrote. “On the other hand, I would be very happy if you could contribute to the practical structural aspects of the settings which are within your domain, that is to say the knack of a practical woman, talented and kind at the same time.” He would ultimately have Perriand design the kitchens and apartment furnishings, declaring, “the kitchen in Marseille should become the centre of French family life,” based on ideas for a modern, labour-saving kitchen. Taking those ideas further, Perriand developed a modular kitchen with built in cabinets and what were, for the time, advanced features (an electric stove with an oven and fume hood, and a sink with an integrated waste disposal unit); it heralded a new, liberated role for women.

Saint Sulpice dining room, designed by Perriand © Archives Charlotte Perriand

Through her work, Perriand wanted to bring the progress of modernity to the largest number of people; “there is art in everything,” she explains in her autobiography, “whether it be an action, a vase, a saucepan, a glass, a piece of sculpture, a jewel, a way of being”. As part of the post war reconstruction, Perriand was commissioned to design furniture and fittings for 39 student rooms at Jean Sebag’s Maison de la Tunisie, Cité Universitaire. Perriand was contracted to Atelier Jean Prouvé to use sheet metal, and so updating her sliding Nuage shelf units she created the now iconic polychromatic Tunisie bookcase. By the late 1960s, Perriand was immersed in an even bolder scheme for the apartments at Les Arcs, a sprawling ski resort in France's Tarentaise Valley, in which she ensured the mountain views were preserved by building into the incline and sloping roofs downwards.

Perhaps the most evocative places to experience Perriand’s work are her own homes, the Méribel chalet and the Paris apartment she designed in 1972. Perriand bought the apartment when Martin fell ill, after charging Pernette with finding a home near her design studio with views for him to enjoy. Occupying the attic of an apartment building, it offers a magnificent views of Paris, from Sacré-Coeur in Montmartre to the Eiffel Tower. “I searched and searched, but everything was too expensive,” Pernette recalls. “I thought this place would be too small, but when Charlotte saw the view, she said, “‘Okay, we’ll make it work. We’ll live as if we’re in a ship’s cabin.’” Perriand designed screens to slide across the shelves to disguise or reveal more books and a tiny TV set. Tucked in a corner is her old record player. “Charlotte loved music and had a wonderful singing voice,” Pernette says. “We’d all sing together in the evenings in Paris and Méribel, and I so regret not having recorded her.”

Throughout her career, Perriand dedicated herself to maintaining a standard quality of life, no matter where the location or type of building: whether working-class housing developments, urban or rural dwellings, mountain refuges and hotels, she always approached her projects with the interest of humankind and environment in mind, by creating furniture which is both comfortable and functional. Prouvé once said she was one of the rare designers blessed with spontaneous harmonic contemporary thought. Perriand worked hard to lower costs and expand access to beauty and comfort; but late in life she became dissatisfied with the consequences.

She had dedicated herself to establishing a connection between art, industrial production and the commercial market; yet despite her best efforts, she never succeeded in her endeavour to make furniture that was affordable en masse. She had hoped her tubular steel furniture would go down this route, but ultimately, discussions with manufacturers proved unfruitful: “Our attempts at talks with the Peugeot bicycle company resulted in half an hour of total incomprehension,” she recalled. She was also dismayed that bringing leisure to the masses was leading to “loss of the very qualities people have come to enjoy” because vast car parks, enormous housing developments and the provision of access roads to every site of natural interest, was burying them under landfill. “We have been overtaken by the evolution of the machine,” she told Architectural Review, calling for “a return to much smaller scales of operation”, centred on craftsmen and artisans.

Perriand’s works stand among the lasting classics of the modern movement. As an interior architect, she constantly evolved in her aesthetic line of design: even at the time of her death, she was exploring the possibilities of using carbon fiber and softer materials. “Nothing is off the table; there is no single answer,” was one of her favorite expressions. When asked by Hendel Teicher in an interview for Art Forum in 1999 what advice she would give to a young woman who said “Charlotte Perriand, I would like to do what you do”, she replied: “It doesn't happen out of the blue. It's difficult. I had the good fortune to study at the Ecole des Arts Decoratifs with professionals. The only advice I would give would be to stay within the reality of things, that is, the execution, the concrete. And then, she would have to make herself known, produce little things, show them, etc.”

Ben Weaver

B306 Chaise Longue (1928) designed by Perriand, pictured at Villa la Roche © Archives Charlotte Perriand

Dining Room 28 (1929), Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Charlotte Perriand © F.L.C. / Adagp, Paris, 2019 © Jean Collas / AChP