Social Responsibility

Ethical interiors

“Original minds are not distinguished by being the first to see a new thing, but instead by seeing the old, familiar thing that is over-looked as something new.” — Friedrich Nietzche

When one talks about “social responsibility” and making more “ethical” choices, one immediately thinks of environmental matters, and whist that is clearly part and parcel of the topic at hand, it also encompasses “awareness”, i.e. educating oneself when it comes to matters of design and making choices that benefit the design world at large. In recent years we’ve seen fashion and interiors become increasingly intertwined, and accordingly, as people en masse are spending more on their homes, the high-street concept of “fast fashion” has been transplanted into homewares; a growing area for stores like Zara, Anthropologie, H&M and French Connection, who have, quite understandably, taken advantage of a burgeoning retail phenomenon. This new found national obsession with interior design is not attributable to any one factor, but some are perhaps more obvious than others. First, during the pandemic we were faced with the harsh realities of or homes, what worked, what didn’t (some London workers had barely seen their apartment in the light of day before lockdown orders went into effect in March 2020), and a good many felt the inclination to feather their nests, so to speak, improving their immediate environments, which, as well as the obvious aesthetic aspect, has the welcome result of improving mental wellbeing. Of course, this may well be fairly temporal phenomena. As things gradually return to normal, people will, inevitably, spend less and less time in their homes, and more time socializing. It’s quite possible we will see a fairly quick return to post-pandemic norms, when convenience of location and proximity to bars and restaurants often outweighed square footage and natural light. Or, perhaps, quite the opposite — as if the trend for working from home continues, the desire to invest and improve might even gain momentum. Looking at long-term factors, print magazines have, for a good many years been pushing the lives of celebrities in order to shift copy; and after Vogue starting using celebrities and “reality” stars as cover models, similarly the “bibles” of interiors, Architectural Digest, Elle Decor etc., followed suit, and started featuring their homes. Very quickly the two started to merge into one, and after seeing shoot after shoot of the homes of serial flippers Ellen DeGeneres and Portia de Rossi, other members of the A-List wanted in on the action; desperately enlisting the services of interior designers so as to turn their naff pleasure palaces into minimalist, art-strewn, editorially pleasing bastions of style. It was no longer enough to dress in the latest fashions, actors, actresses and models had to transform their lives into a Gesamtkunstwerk (“a total work of art”), where every aspect, from hair and makeup to kitchen and sanitary ware, was glossy, styled and camera ready.

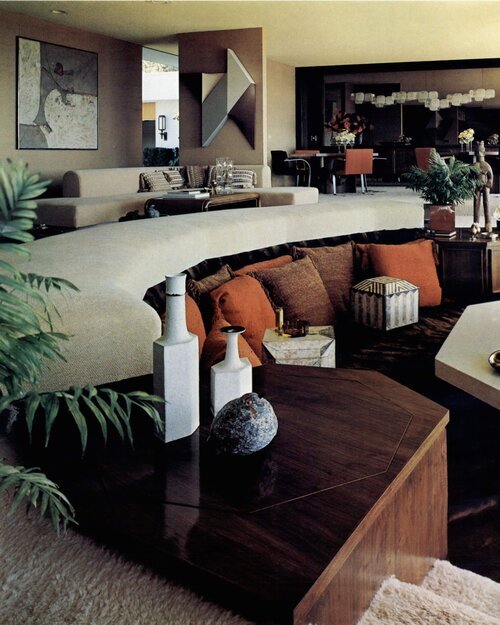

An interior by Arthur Elrod in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, the sort of mid-century interior currently in vogue, image c/o Vendome

An duplex on New York’s Upper East Side designed by Robert Stilin, a designer who frequently uses more unusual pieces to create truly original interiors, image c/o Vendome

Gradually there was a trickle-down effect, and suddenly a well curated interior became as desirable as a well curated wardrobe; even cult television show Sex and the City started to incorporate interior design as an integral part of its increasingly dysfunctional story lines — with Carrie’s newly-engaged-apartment-re-design a Jungian reflection of her improved psychological state. Social media and in particular, Instagram, has further helped contribute to the democratization of interiors, and in turn, came the “lifestyle” and interiors bloggers, who, through carefully primping and preening their homes, employing a tick box list of tried and tested trends, for e.g. fiddle leaf figs, wicker and 1970s teak furniture, hoped to gain followers, and, ultimately, lucrative sponsorship deals with companies like Diptyque and Jo Malone. The problem is that as celebrity interiors became ever more visible, one soon started to see, especially in LA, that certain items of desirable mid-century furniture became almost de rigueur amongst the A-list. In particular, Charlotte Perriand’s (1903-1999) tripod stools, Serge Mouille’s (1922-1988) spider-like light fittings and Jean Royère’s (1902-1981) sinuous Flaque coffee table were seen again and again (or rather, an influx of imitations, with one US-based company currently knocking out “Royère” furniture at a rate of knots). Once the preserve of seasoned collectors, rarely seen in glossy interiors magazines, they were suddenly everywhere, along with the work of Pierre Paulin (1927-2009), Jean Prouvé (1901-1984) and Pierre Chapo (1927-1987) et al, creating an eclectically curated aesthetic, the combination of which could almost be seen as a homogenous twenty-first century interior “style” in the same sense, for e.g. as Art Nouveau or Art Deco; the signatures of which being cane seating, wavy edged furniture, enveloping sofas clad in teddy-bear velvet, black glazed ceramics and a preponderance of tubular steel. The problem is that the majority of the general public, and for that matter, in large part, the interiors industry, has very little design knowledge; they don’t care how important X, Y or Z piece is to the canon of twentieth century art. Often or not, when a client approaches a designer, and wants to achieve a certain “look”, they have no idea about the provenance of the furniture in their torn out mood imagery, who it’s by and where it came from, and have very few qualms about having it copied when a tight budget precludes the use of originals, or even, for that matter, official replicas and re-editions.

An interior by by Robert Stilin, demonstrating his eclectic approach to interiors, and that there are alternatives to the same mid-century pieces seen ad infinitum, image c/o Vendome

Of course, certain pieces by the design greats are now fetching astronomical figures, and are far outwith the reach of anyone but the 0.01%, i.e. the clients of those super-star designers, the likes of Pierre Yovanovitch (b. 1965) (who has a particular penchant for the work of Axel Einar Hjorth (1888-1959) and Paavo Tynell (1890-1973)), Axel Vervoordt (b. 1947) (who filled Kim Kardashian’s monastic 9,000-square-foot Bel Air mansion with a panoply of Jeanneret’s “Chandigarh” furniture) and, of course, perennial celebrity favourites, the mother-and-son duo Clements Design. Recently at auction, even during periods of lockdown, the prices of such sought-after furnishings have gone through the roof. When in the late 1980s and early 1990s power-house gallerists such as Jacques Lacoste and Alan Grizot “re-discovered” certain twentieth century masters, for e.g. Georges Jouve (1910-1964), Mathieu Matégot (1910-2001) and Alexandre Noll (1890-1970), all of whom had somehow fallen under the radar, or rather, fallen out of fashion, re-contextualizing and re-introducing them to a new market, they were not at all cheap, as one might expect; but, they were still affordable to middle class collectors who appreciated good design and were willing to pay a premium — whereas now, this is simply not the case. Even when things started to snowball, and the most desirable of pieces were selling for figures considered eye-watering to some, they were still a relative bargain compared to today’s prices; for e.g. in 2009 Phillips auction house sold a whimsically rotund Ours Polaire (“Polar Bear”) sofa for £133,250, whereas the same model sold at Christie’s Paris in June last year for just short of £1m. These sorts auction records are too steep even for the most image-conscious of A-list celebrities; with poor Kanye West admitting in a 2020 interview with Architectural Digest, “I sold my Maybach to get the Royère” (and this was even before he’d stumped up for eight prototype versions of Kim’s Vervoordt/Silvestrin designed mortuary-slab-chic bathroom sink). Whilst we can hardly blame the design-dealers and auction houses selling at such inflated, unrealistic prices (after all, there are people out there willing to pay them), the problem now is that everyone wants the same look, and by and large they simply can’t afford it. As a result, interior designers are resulting to fakes and knock-offs as a means of creating the appearance of an eclectically curated, mid-century-heavy pad on a tight budget — as highlighted by the anonymous Instagram account @DesignWithinCopy, which has been shining a light on many of those interior designers and decorators who think nothing of ripping off another’s work verbatim. The answer, is of course, originality; the creative industry at large needs to drop its Pinterest approach to design, and instead, focus on producing interiors which, when inspired by the past (as inevitably they will, and should be) are reinterpretations and not carbon copies.

An apartment in Tribeca, New York, designed by Alyssa Kapito, a designer whose original, contemporary interiors are truly timeless, image c/o Alyssa Kapito

Quite simply, for all those interior designers having twentieth century and contemporary furniture reproduced when unaffordable (in the case of the latter, a good many are even shameless enough to ask for dimensions and measurements in a pretence at placing an order), instead, do your job, design something new, have that made, and not a shoddy approximation of someone else’s work. This will, inevitably, make the job more difficult, it will take more time (and for that matter, separate the wheat from the chaff), but it’s the ethical thing to do, and the only way to move design forward, and perhaps, to give smaller makers and producers more of a chance against those high street behemoths resorting to slave labor so as to churn out mass produced tat that will, inevitably, end up at the bottom of a landfill. This is also something particularly relevant to the hotel and leisure sector, as interior designers will often send lists of furniture for procurement knowing full well that originals are out of budget, and that they will likely be knocked off with the pre-requisite “nine points of difference”. Of course, if the consumer really cared, ethically speaking, fast fashion and interiors simply wouldn’t exist, and so clearly there needs to be some attempt at re-education and encouraging people to buy less and buy better. This is, whichever way one approaches it, an incredibly complex area, and one that is difficult to address; many of those now considered to be “design icons”, Perriand, Prouve and Le Corbusier for e.g. had the egalitarian idea of making good design available to all — and whilst there was, indisputably, progress, they never quite achieved that lofty ambition. Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. Whilst high-street stores like Conran and Heal’s, and for that matter, official reproductions of design classics, from Cassina and ARAM et al, are out of reach for many, there are some more affordable retailers, IKEA and MADE.com for e.g., who produce original, contemporary furniture that is far more affordable. If people were to trust their own taste, rather than attempting to create an approximation of something seen in print, choosing the best they can afford, and pieces that are well made, and will last, the world would surely be a better place for it. It’s the role of the interiors sector to inform, to educate and to convince people that it’s the right way to go, as without a strong, unified voice, there’s very little hope of things changing. One thing however is certain, for those professionals working within the interiors sector, there really is no excuse; they should already know better, as an industry built on “trends” is entirely reductive and serves to set good design back.