Masculine Decor

Sexuality and Interior Design

“In a patriarchal society, masculine gender-identity is often moulded by violently toxic stereotypes…It’s time to celebrate a man who is free to practice self-determination, without social constraints, without authoritarian sanctions, without suffocating stereotypes.” — Alessandro Michele, creative director of Gucci.

Interior design is inherently very personal, and inevitably there will be a difference between those spaces conceived either by or for men and women. For much of the twentieth century, the traditional, normative model of gender identity was grounded in strong, and opposing, differences; associating femininity with domestic space, unpaid housework, body and emotions, and masculinity with public space, paid work, mind and rationality. These gender asymmetries are of course premises for power relations based on social inequalities, reproducing and reinforcing hegemonic masculinity. Yet, seemingly, in terms of interiors, the “masculine” arena of production and the “feminine” domain of consumption were not defined in such absolute and finite terms. This can be seen in the representation of the “bachelor pad” in Western culture, which is demonstrative of how as the twentieth century rolled on both men and women were targeted by the advertising sector apropos the commodification of interiors, architecture and art. From its very inception in 1933, American men’s magazine Esquire gave column inches to sleek, stylish bachelor apartments and, inherently, as has always been the case with print media, there was an emphasis on exploiting the image as a totem of forward-looking and “liberated” masculine consumerism. The bachelor pad was essentially portrayed as a sleek sovereign kingdom, a stylish bolthole for a modern masculine lifestyle, liberated of familial responsibilities and work ethics, where men could relax and unwind in sybaritic luxuriance. Contemporaneously speaking its ultimate visual manifestation might be the glass-sheathed penthouse apartment of American philanthropist and patron of the arts Charles Templeton Crocker (1884-1948) — the Union Pacific Railroad heir, nicknamed “Prince Fortunatus” by his classmates at Yale — who hired none other than Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941), Pierre Legrain (1889-1929), Jean Dunand (1887-1942) and Madame Lipska to execute the decor for his newly acquired San Francisco eyrie. As soon as his divorce from socialite and sugar heiress Helene Irwin (1887-1966) was made final, Templeton Crocker moved into the penthouse with longtime friend and valet-butler Thomas Christian Thomasser (1884-1848). Described by Vogue as “perhaps the most beautiful apartment in the world”, guests marvelled at aquariums full of exotic fish, dramatically illuminated and set beneath the floors, as well as lacquer panelling, walls clad in straw marquetry and fire surrounds in rose quartz, mica and bronze. Particularly alluring, Crocker’s personal bathroom had been built around a semicircular black tub with matching fixtures, which might very well have inspired the decor in Frasier Crane’s now-iconic Elliott Bay Towers apartment.

An apartment in a building by Gustave Eiffel on rue Martel in Paris’s tenth arrondissement, designed by Italian interior architect Fabrizio Casiraghi

American architect John Lautner’s Schaffer House (1849) , used by fashion designer and director Tom Ford in his 2010 film A Single Man

Very soon the bachelor pad — chic, cosmopolitan and overloaded with à la mode luxuries — came to be portrayed in media and advertising as a visual and spatial representation of the male consumer, which during the retail boom of the 1950s and ‘60s became a pervasive stereotype. During this period as demonstrated by television series and films such as Man from UNCLE (1964) and, of course, the James Bond Franchise, the idea of a gadget-laden “bachelors lair” became a recurring theme; essentially used as a leitmotif for hedonistic pleasure and desire. Since then the bachelor pad, which has been represented variously in the media as anything and everything from that designed by architect Frank Ghery (b. 1929) for the pages of Playboy magazine (a three-story townhouse with mirrored walls, a translucent glass tub and murals of female nudes, the latter of which were designed by the architect’s son) to a studio with duct-taped recliners, beer can sculptures and plastic cups. The distinction between “feminine” and “masculine” interiors was something of a hangover from the nineteenth century when home decorating manuals placed an emphasis on heavily gendered spaces; the parlour, reception and morning rooms, considered feminine, were decorated in light, airy colours; whereas the dining, smoking and billiard rooms, as well as the library and study (for “serious work”), were masculine, identified by solid, dark wood furniture, brass lamps, button-back leather sofas and hunting trophies. Before that things were far more fluid in terms of interiors and dress and menswear in the eighteenth century was just as glamorous as that of women, with elaborate silks, wigs, white hair powder, perfumes and stockings all perfectly the norm for any fashionable gent about town. Indeed for centuries, pink clothing in shades of Magenta, salmon and fuscia had been the ultimate symbol of wealth and power in Europe, not only symbolically speaking as a descendant of red, the hue of strength and virility, but also due to the monetary implications of importing expensive dyes from South Asia and South America. It was a moment where, with the “culture of politeness”, as espoused by the third earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713), which placed an emphasis on the importance of understanding and appreciating the treasures of Greek and Roman antiquity, classical ideals began to permeate all areas of architecture and fashion; for example, in a quintessential “Grand Tour” portrait, executed in 1759 by Italian artist Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787), British landowner, politician and botanist Richard Milles (c. 1735-1820), resplendent in shades of blushing pink (including Batoni’s own fur-lined cerise cape), gestures languidly toward a map of Rome as a means of indicating his learned erudition.

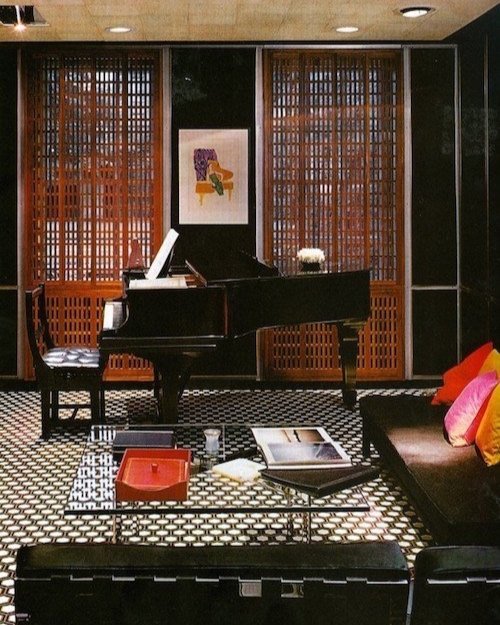

A dark and moody interior (c. 1965) by English decorator David Hicks, demonstrating the sort of slick, sophisticated bachelor pad made popular in the mid-twentieth century

An interior by American designer Robert Stilin, which is perhaps representative of a contemporary approach to masculine interior design

Whilst embedded in tradition, masculinity was certainly not sedate, and it became so in large part due to the toned-down inclinations of English dandy Beau Brummell (1778-1840). For many years the very arbiter of elegance in London society, Brummell eschewed the elaborate trappings of French court dress in favour of a more subdued palette of blue, buff and black, which would, in turn, become the catalyst for “The Great Masculine Renunciation” — that being a major turning point in the history of fashion when men effectively relinquished their claim to adornment and beauty. Some have argued that, despite its inherent whimsy and extravagance, the former accoutrements of fashionable eighteenth-century dress, which included anything and everything from florals and brocades, to jewelled buckles and lavish and elaborate beauty regimes, were all forms of the highest form of masculinity, that being, elitism (interestingly Brummel’s grandfather had been a shopkeeper, which might perhaps explain his penchant for a more elegant, practical style of dressing, a sentiment later shared by French couturier Coco Chanel (1883-1971), who, in applying similar principles, became a key figure in the emancipation of women’s dress). From that point on, despite an altogether more austere approach to men’s fashion, en masse, many of the ideas we have of what constitutes a “masculine interior” come from the nineteenth-century decorating styles of the English upper classes; austere country piles, painted rich, sombre hues with dark panelled billiards rooms, heavily patterned wallpaper and an abundance of verdant green palms (So utterly ridiculous was the era in terms of the prevalent, repressive attitude to art, design and fashion that upon opening the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1857, the Queen had been so utterly horrified at seeing the stark naked body of Michelangelo’s David, that a codpiece in the form of a figleaf had to be hastily cast in plaster so as to avoid her further blushes). This sort of dour, starchy aesthetic was a style that in turn would be adopted by a myriad buttoned-up London gentleman’s clubs, such as Brooks’s, the Carlton and the Carlyle, which have themselves over the years inspired and continue to influence countless designers.

Discussing a recent project, a third-floor apartment in a building by Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923) on rue Martel in Paris’s tenth arrondissement, Italian interior architect Fabrizio Casiraghi (b. 1986) opines: “[The client] wanted something very masculine, something that is Parisian but not typically Parisian, something international, because he has a huge job and travels a lot, when he comes home he wants a cosy space.” So as to channel his client’s aspirations, the designer, in turn, was inspired by English heritage, the private clubs of London and, in particular, “the definition of a cigar room”, which was translated into an extraordinary interior clad in glossy green lacquered panels, with travertine floors and an eclectic mix of elegant twentieth-century furnishings. Referring to the sofa, upholstered in Pierre Frey corduroy — “he asked me for something very masculine, so I used the same fabric as men’s pants” — Casiraghi explains. Similar considerations of atmosphere and environment are of course equally applicable to film and television, for example, at the centre of Netflix’s Oscar-winning film The Power of the Dog (2021) a two-storey craftsman-style ranch acts as a backdrop for the drama that unfolds. Production designer Grant Major designed the house so as to embody the suppressed homosexuality of one of the lead characters, Phil, played by English actor Benedict Cumberbatch (b. 1976). “I really wanted to show that tension in the architecture by making it feel dark and very much like [Phil’s] hyper-masculine, alpha male kind of environment,” says Major. In doing so, he used dark tones, such as browns, reds and blacks, as well as a plethora of taxidermy animals, which are, apparently, a reflection of the character’s dark side: “I wanted to show all those hints, those taxidermy pieces around the walls, staring out at you with their glass eyes – that’s very much him, the violence of those taxidermy pieces but beautifully mounted on a wall.” Similarly, the interiors that fashion designer and director Tom Ford (b. 1961) created for his films A Single Man (2010) and Nocturnal Animals (2016) might again be thought of as “hyper-masculine”, especially, in the case of the former, architect John Lautner’s (1911-1994) Schaffer House (1948), whose austere, moody palette of timber and muted shades of taupe and beige serves as an appropriate backdrop to protagonist George’s life, as he mourns death of his long-term partner Jim in a car crash. Despite what might be thought of as a prevailing masculine aesthetic, not only on screen but in terms of the designer’s own minimally furnished homes, Ford has said “I hate those two words, feminine and masculine. I mean what are they? Why is a suit masculine and not feminine?”, and in reference to his fragrance Noir Anthracite, “I think most men would smell it and instantly think it was masculine … but to me, it’s just a very classic men’s fragrance. It’s perhaps more men-centric but essentially I create unisex scents”. Whilst a little difficult to unpick, it would seem Ford’s problem is not so much an item of clothing or jewellery etc. being associated with the male or female gender, but rather the idea that it is for the exclusive use of one or the other sex, so that for e.g. a floral fragrance can be worn by both men and women without fear of judgment or prejudice.

There are those of the school of thought that the terms “masculine” and “feminine” should no longer be used when writing about interiors and decor period, on the basis that they are both, inherently, stereotypes, and that a writer who channels such stereotypes without recourse to ironic distance is essentially nothing more than a “hack”. This stems from the idea that feminity, by and large, is considered almost as if an additive, which in the realm of interior design, translates to curtains, cushions and soft furnishings, i.e. those items that are transient and ephemeral. Ergo, by suggesting spareness and raw architecture are “masculine” qualities, it implies traditionally “feminine” decor is frivolous, and that those who associate themselves with femininity are simply not as relevant. This brings to mind twentieth-century great Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) who, on completing her studies, applied to work in the hallowed studio of the great modernist architect Le Corbusier (1887-1965): “The austere office was somewhat intimidating, and his greeting rather frosty,” Perriand wrote in her memoirs. “‘What do you want?’ he asked, his eyes hooded by glasses. ‘To work with you.’ He glanced quickly through my drawings. ‘We don’t embroider cushions here,’ he replied, and showed me the door.” In contemporary society, the idea of sexuality is becoming less binary and far more fluid; and in turn, we’re seeing the rise of “hybrid masculinity”, whereby heterosexual men are drawing on elements of feminized or marginalized masculine identities and incorporating them into their own gender identities. Simply put, men are behaving differently, taking on politics and perspectives that might have been understood as emasculating a generation ago, and that seem to bolster (some) men’s masculinities today. Whilst all of this might seem a step in the right direction with regards to breaking down unhealthy gender stereotypes, at the same time it’s worth keeping in mind that only last year, China’s government banned “effeminate men” on television, telling broadcasters to “resolutely put an end to sissy men and other abnormal esthetics”, as a means of tackling the nations so-called “masculinity crisis”. Similarly, Florida’s controversial “don’t say gay” bill was passed this month, with the aim of restricting schools in the Sunshine State from teaching students about sexual orientation and gender issues.

“A dominant, winning, oppressive masculinity model is imposed on babies at birth,” postulates Alessandro Michele (b. 1972), creative director of Gucci. “There is nothing natural in this drift … it’s time to celebrate a man who is free to practice self-determination without social constraints, without authoritarian sanctions, without suffocating stereotypes.” Of course, it’s unnecessary to unpick masculinity just for the sake of doing so, and the rise of hybrid masculinity can be seen increasingly in attitudes to interior design, where elements of decor once viewed as “feminine” are no longer taboo. Whilst the bachelor pad was at one stage a midcentury institution and, to butcher Corbusier’s modernist edict, “a machine for living large”, to use the term in a contemporary sense to describe the homes of single men might be something of a misnomer, as over the years it has been thoroughly degraded, bringing with it somewhat negative connotations of a pigsty aspiring to the aesthetic of an unmopped sports bar. Today, the image of a “bachelor pad” as seen in television, film and print media tends to be a pristine amalgam of mid-century furnishings by the likes of Jean Prouvé (1901-1984), Hans Wegner (1914-2007) and Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969), set against a background of white walls and abstract art; in essence a softer version of Patrick Bateman’s slick, streamlined apartment in Mary Harron’s (b. 1953) American Psycho (2000) — which itself features an impressive art collection, including pieces from Robert Longo’s highly acclaimed “Men in the Cities” series (chosen by production designer Gideon Ponte as the artist’s larger-than-life photorealistic drawings of suited men and women in poses of contorted agony explore questions of masculinity, politics and power in society). Similar, though less austere, the so-called “bachelor studio” of Yves Saint Laurent on Avenue de Breteuil, Paris designed by French decorator Jacques Grange (b. 1944) features an elegant mixture of ethnographic art and furniture by the likes of Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941) and Eyre de Lanux (1894-1996). To my mind, I agree with the distinction Ford seems to be making, in that to use the terms “masculine” and “feminine” in the realm of interior design is not inherently negative, but becomes so when employed in the exclusionary sense of suggesting a man or woman shouldn’t use for example a floral fabric or a floor-grazing ruffle around the base of an armchair on the ground it’s inappropriate for either one or the other sex. Essentially, and the crux of the matter, societally speaking, it’s time to grow up and to leave such divisive schoolyard mentalities in the past where they belong.