Destruction of the Father

Louise Bourgeois

“This spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver. Like spiders, my mother was very clever. Spiders are friendly presences that eat mosquitoes. We know that mosquitoes spread diseases and are therefore unwanted. So, spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother” — Louise Bourgeois

A second-generation surrealist, Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010), the French-born American artist who claimed to be named after Louise Michel (1830-1905), the “red virgin of Montmartre”, an important figure of the French Commune (but in actuality named after her father, Louis, who had wanted a son), was infamously known for her anarchist feminist politics. Considered to be one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, in a career spanning seventy years, she produced an intensely personal body of work that is as complex as it is diverse. Born on Christmas day on the Left Bank in Paris, she was the middle child of wealthy bourgeois parents who owned a gallery in Paris, where her father sold antique tapestries, and a tapestry restoration workshop in Choisy-le-Roi and, later, in Antony, run by her mother, Joséphine. (Bourgeois’s incorporation of tapestry into her wider practice draws on personal memories of working alongside her mother in the workshop.) After receiving her baccalaureate in philosophy from the prestigious Lycée Fénelon in Paris, she entered the Sorbonne to study mathematics and differential calculus, finding in Euclidean geometry a safe haven from family turbulence. When Borgeois’ mother died in 1932, she attempted suicide, apparently provoked by her father’s mockery of her grief, and subsequently, profoundly depressed, she abandoned mathematics and switched to the study of art: “In order to stand unbearable family tensions, I had to express my anxiety with forms that I could change, destroy, and rebuild.” Her father thought modern artists were wastrels and refused to support her, and so, over the next several years, she took courses at the École des Beaux-Arts, and art history classes at the École du Louvre, where, so as to pay her tuition, she became a docent, and a guide at the Musée du Louvre. She began by painting, harking back beyond the Surrealists and Cubists, to Cézanne and Matisse. Later, Bourgeois recalled the moment that, “[Fernand] Léger turned me into a sculptor.” She had persuaded the French modernist to let her study with him, in return for English translation. He had hung a spiralling wood shaving on a shelf and asked his students to draw it. At that moment, Bourgeois realised: “I did not want to make a representation of it. I wanted to explore its three-dimensional quality.”

She met her American husband, the art historian Robert Goldwater in 1938, while he was on a trip to Paris, and as she put it: “In between talks about surrealism and the latest trends, we got married.” He was a member of New York's intelligentsia, and was friends with Alfred Barr – the first director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), as well as with renowned art collector Peggy Guggenheim and all of the better-known abstract expressionists. Bourgeois emigrated to New York with him only to find, after the war broke out, that she was quickly re-joined in America by her old artistic compatriots, including, amongst others, Le Corbusier, Joan Miró and Marcel Duchamp, all of whom contributed to a cosmopolitan, avant-garde scene. Bourgeois had her first solo show, “Paintings by Louise Bourgeois,” in 1945 at the Bertha Schaefer gallery, and then took part in two group shows with abstract expressionists including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Robert Motherwell, the first at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the second, “The Women” at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery. Four years later, at the Peridot Gallery in New York she had her first exhibition of sculpture, “Louise Bourgeois, Recent Work 1947-1949: Seventeen Standing Figures in Wood” — an installation of potent wooden figures, tall, pole-like, some more figurative, some less so — that she intended as abstract portraits of family members and friends. “These pieces were presences…” she later said, “missed, badly missed presences… I was less interested in making sculpture at the time than in re-creating an indispensable past.” Just as Bourgeois was beginning to make a name for herself, her father died in 1951 causing her to retreat from the New York art scene. She did not, however, stop working. Her totems became assemblages, exploring a deeply personal narrative, revolving around the themes of architecture, memory, and the five senses. Bourgeois later said: “To do an assemblage is a nurturing mechanism… it is not an attack on things, it is a coming to terms with things…”

Portrait of Louise Bourgeois

Nature Study, biscuit porcelain (1996, cast 2004) by Louise Bourgeois

Bourgeois gained fame only late in life, when in 1982, at 70 years old, MoMA gave her a retrospective — the museum's first one-person survey of a woman artist in well over 30 years — after which she received the critical and popular acclaim that had long eluded her. The specific agent of change was feminism, and the art world’s new pluralism, and in particular, the insistence of feminist artists and critics that we look hard at what for whatever reason was considered “marginal” in art, and the very notion that a “mainstream” existed. Part of a genuine avant-garde, Bourgeois resisted assimilation, choosing instead to remain at the periphery of the “scene”, with a sole focus on the exploration of her own obsessive preoccupations. Though she rejected the polemical premise of an exclusively feminist aesthetic, through manipulating gender metaphors — long before feminism had taken hold in either France or America — she inspired generations of future female artists for whom she set a precedent. Her reputation grew stronger in the 1990s, when, in the context of the body-centred art, with its emphasis on sexuality, vulnerability and mortality, her psychologically nuanced — often nightmarish — abstract sculptures, drawings and prints had a galvanizing effect on the work of younger artists, and in particular, on women.

Bourgeois’ sculptures in wood, steel, stone and cast rubber, often organic in form and sexually explicit, emotionally aggressive yet witty, covered many stylistic bases. Iconographically speaking, Bourgeois’ work being non, or even anti figurative, is often grouped with the abstract expressionist artists. At the same time, Bourgeois’ works were far from abstract, instilled with penetrating biographical symbolism and psychological motifs, thus militating against an iconographic “reading off the page” or translation according to a dictionary-based mode of reading. Despite the diverse nature of her oeuvre, a set of themes are repeated, all centred on the human body and the need to nurture and protect it from a frightening world; one which affected women disproportionately. From her sketches of the 1940s, right through to her death in 2010, she breathed life into both structure and texture in order to express themes of loneliness, vulnerability and pain. “I have a religious temperament,” Bourgeois, a professed atheist, said about the emotional and spiritual energy that she poured into her work. “I have not been educated to use it. I’m afraid of power. It makes me nervous. In real life, I identify with the victim. That’s why I went into art.”

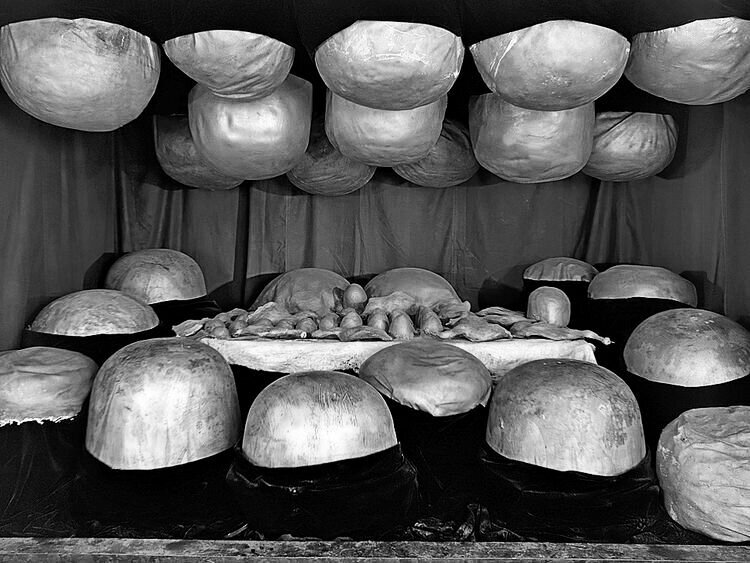

The Destruction of the Father (1974) by Louise Bourgeois

The prevalent theme of protection can be seen in images of shelter or home, as Bourgeois blended artistic mediums with her personal conflicts and traumas. For example in the early 1960s, the “lair” emerged as a motif in her work, referring to cocoons or places where creatures of the natural world could live and be protected. The Quartered One and another lair from this period, were the first hanging works that Bourgeois created, which, as she explained, were symbols for precariousness. “The lair is a protected place you can enter to take refuge,” Bourgeois said of the work, whilst also acknowledging the possibility of isolation: “The security of the lair can also be a trap.” Similarly, in Bourgeois’ Maisons Fragiles (1978), an ode to vulnerability, a precariously balanced series of sculptures, resemble houses, ever threatening to topple. These sculptures are a commentary on the solitude of domestic life, confronting the fragile psychology of Bourgeois’s youth. In her series of Cells from the early 1990s, installations of old doors, windows, steel fencing and found objects were meant to be evocations of her childhood, which she claimed as the psychic source of her art. One strand of Bourgeois’ work is that of childhood distress and hidden emotion; the artist spoke publicly and freely of her early, emotionally conflicted family life: her practical and affectionate mother, contracted influenza when Bourgeois was young; her domineering father, who, after her mother became ill, began having affairs with other women, most notably with Sadie Gordon, her teenage governess, while belittling his wife and daughter who both had to pretend nothing was happening.

This dysfunctional family model left an indelible mark on Bourgeois’ psyche, sowing the seeds of reproach and insecurity which, she said, would later become the source of her engagement with the double standards assigned to gender and sexuality. She recalls her father saying “I love you” repeatedly to her mother, despite infidelity. Cell: You Better Grow Up (1993) directly reflects Bourgeois’ childhood trauma and the insecurity that surrounded her because of her unstable family situation. Her highly idiosyncratic style relies on an intensely personal vocabulary of anthropomorphic forms and the suggestive, and often grotesque shapes that her sculptures assume — the female and male bodies are continually reshaped to be almost unrecognisable, or at least, uncanny – are charged with sexual allusions, as well as symbols of childhood innocence, and the sometimes disturbing interplay between the two. In an illustrated autobiographical text called Child Abuse published in the December 1982 issue of Artforum — which came out just before her first major retrospective exhibition was due to open a MoMA — Bourgeois sensationally revealed the traumatic story of her childhood. In the accompanying text to an image she wrote “I am a pawn. Sadie is supposed to be there as my teacher and actually you, mother, are using me to keep track of your husband. This is child abuse.”

“Adhering to a strict economy of graphic means, [Bourgeois] was able to preserve images that welled up from the most profound reaches of her deeply informed imagination, one of startling and elemental clarity and strangeness” — Robert Storr

It was her portrayal of the human form, the body itself, sensual but grotesque, fragmented, often sexually ambiguous, that could provoke or shock, cementing Bourgeois status as an unforgettable and unrepeatable talent. “I break everything I touch because I am violent,” she once said. “I destroy the relationships I have with my friends, lovers, children.” In some cases the body took the abstract form of her totem-like Personages — some bronze, some wood, one with wings, one with nails driven into it, and so on — that she grouped together to create installations; in Décontractée (1990), two finely carved hands lying, palms open, on a massive stone base, suggest the relaxation and release that might follow a painful experience. Among her most familiar sculptures was the much-exhibited Nature Study (1984), a headless sphinx with powerful claws and multiple breasts. Perhaps the most provocative was Fillette (1968), translated as “Young Girl”, a 2ft-long, detached latex phallus, suggestive and provocative in its interpretation of female sexuality and latent distrust of male figures which perhaps stemmed from her childhood memories of her father’s affairs.

Exemplary of these feelings was her nightmarish tableau of 1974, The Destruction of the Father, a psychological exploration of the power of the father. A womb-like room made suggestively to resemble either a dining room or a bedroom, Destruction of the Father was the first piece in which Bourgeois used soft materials on a large scale. Bourgeois bought hunks of mutton and beef, decidedly on the bone, cast them in plaster and then covered the plaster with latex rubber. She put them in a cave-like structure, dramatically lit with red lights, the installation designed to look like the aftermath of a crime. The room hosts an arrangement of breast-like bumps, phallic protuberances and other biomorphic and sexually suggestive shapes in soft-looking latex that suggest the sacrifice of an overbearing father. Bourgeois suggested that the tableau’s inspiration arose from a childhood fantasy in which she imagines a dinner at which her family, tiring of hearing the father’s satisfied boasts, dismember and cannibalise him; thus pushing and tipping the power struggle for authority from her father’s grasp to Bourgeois and her siblings. Rather than being an active participant in this massacre, Bourgeois places herself, and the viewer, as spectators observing the drama, as if in a theatre. She is imbuing the work with her feelings and emotions as a way of purging fear by aggression; and, she added, it was confined to her art. Indeed, after leaving home, Bourgeois grew to love her father and she was devastated when he died.

Maman (Spider) (1999) by Louise Bourgeois

So often with Bourgeois’ work, it’s the contradictions that stay with you, and beside the three mysterious metal watchtowers she created for the Tate project of 1999-2000 — one enclosed in a rusted steel skin, two others furnished with large mirrors — stood the first sculpture in what would become an iconic series of giant steel spiders, or Mamans, a highly-charged title for these viscerally imagined sculptures. To almost every other visitor these enormous arachnids, that loom over the viewer, poised and predatory, were fearful and overwhelming, yet Bourgeois saw them as, “portraits of my mother… I want to walk around and be underneath her and feel her protection.” Though the spinning they represented was also a metaphor for the activity of art, Bourgeois made them in remote tribute to the put-upon, patient, inventive, tireless Joséphine: “She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver... spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother”. Indeed she equates its work as a restorer and weaver with her mother and with the busy hands of the women in the tapestry workshop, saying, “I come from a family of repairers. The spider is a repairer.” These are now her most recognizable works, an assertion of both the significance and distinctiveness of female experience. As the critic Jonathan Jones wrote looking back at the Tate’s exhibition: “Bourgeois showed that powerful images dredged from the unconscious can make the most massive space intimate and confessional.”

In an art world where women had been treated as second-class citizens and were discouraged from dealing with overtly sexual subject matter, Bourgeois quickly assumed an emblematic presence. The artist was seen by many as a feminist icon, her career as an example of perseverance in the face of neglect. Intriguingly, this was a title she would utterly reject. She viewed her work as being pre-gender, “For example”, she once said, “jealousy is not male or female.” Bourgeois often spoke of the trauma of abandonment, of anxiety and pain as the subject of her art, and fear: fear of rejection, of the grip of the past, of the uncertainty of the future, of loss in the present. “The subject of pain is the business I am in,” she said. “To give meaning and shape to frustration and suffering.” She added: “The existence of pain cannot be denied. I propose no remedies or excuses.” Yet it was her gift for universalizing her interior life as a complex spectrum of sensations that made her art so affecting. The emotional investment in her work was certainly unique and ground-breaking within the art industry. Bourgeois had an ambivalent relationship with the theory and practice of psychoanalysis and saw art as her parallel “form of psychoanalysis”. She tirelessly, obsessively documented her 32 years of therapy since her father’s death — even writing an essay on “Freud’s Toys” — and transformed the relationship between art and reality. Among others, contemporary art therapists and their patients owe much to Bourgeois’ pioneering work. Towards the end of her life, an editor asked her to pick out a book meant a lot to her. She chose Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan, published in 1954, in which the heroine describes her father: “He was young for his age [and] I soon noticed that he lived with a woman. It took me rather longer to realise that it was a different one every six months. But gradually his charm, my new easy life, and my own disposition led me to accept it”.