Kitschy and Quaint

Maximalism is Back, apparently

“Original minds are not distinguished by being the first to see a new thing, but instead by seeing the old, familiar thing that is over-looked as something new.” — Friedrich Nietzche

Minimalism, in terms of art, design and interiors is often misunderstood — with most people envisaging the sort of sparsely furnished white boxes littering the L.A. hills, with little or nothing in terms of architectural merit, thrown up simply as a means of impressing those who equate square footage with wealth and success. In terms of its origins this conflation of “minimalism” with hostile sterility has more to do with art than design; indeed the term was first used by philosopher Richard Wollheim (1923-2003) in a 1965 essay on Donald Judd (19280-1994), Dan Flavin (1933-1996) and other artists whose oeuvre ostensibly had “minimal art content”. Although it was initially conceptualised as defining the criteria that a work must fulfil so to qualify as “art” in an institutional sense, it soon became synonymous with a group of artists (Robert Morris (1931-2018), Carl Andre (b. 1935), Robert Smithson (1938-1973) and Sol Le Witt (1928-2007) et al) whose output focused on positioning primary geometric objects around an otherwise blank gallery space. “The white wall’s apparent neutrality is an illusion,” the artist and critic Brian O’Doherty (b. 1928) wrote in his seminal 1976 essay, also in Artforum, “Inside the White Cube”. It subsumes “commerce and esthetics, artist and audience, ethics and expediency. It is in the image of the society that supports it, so it is a perfect surface off which to bounce our paranoias.” In other words, whilst the minimalist architectural devices used by such galleries might present the illusion of artistic and intellectual integrity, they are in fact complicit in the problems of capitalism. Going on to discuss the physically empty, but conceptually overloaded conditions for exhibiting contemporary art, he adds, “The wall’s content becomes richer and richer (maybe a collector should buy an ‘empty’ gallery space).” Subsequently, minimalism found its way into the context of various art disciplines, including theatre, music, literature and film. It was first used in the context of architecture and interiors from the late 1970s, almost unnoticed, to describe those works of an extremely reductive — minimal — appearance. Only from the mid-1980s do we see the widespread adoption of “minimalism” and “minimal architecture” to describe a new design movement characterized by a combination of basic essentials, context and place, emptiness, infinite space, limited colours, simplicity, and the use of concrete, glass, natural materials and light.

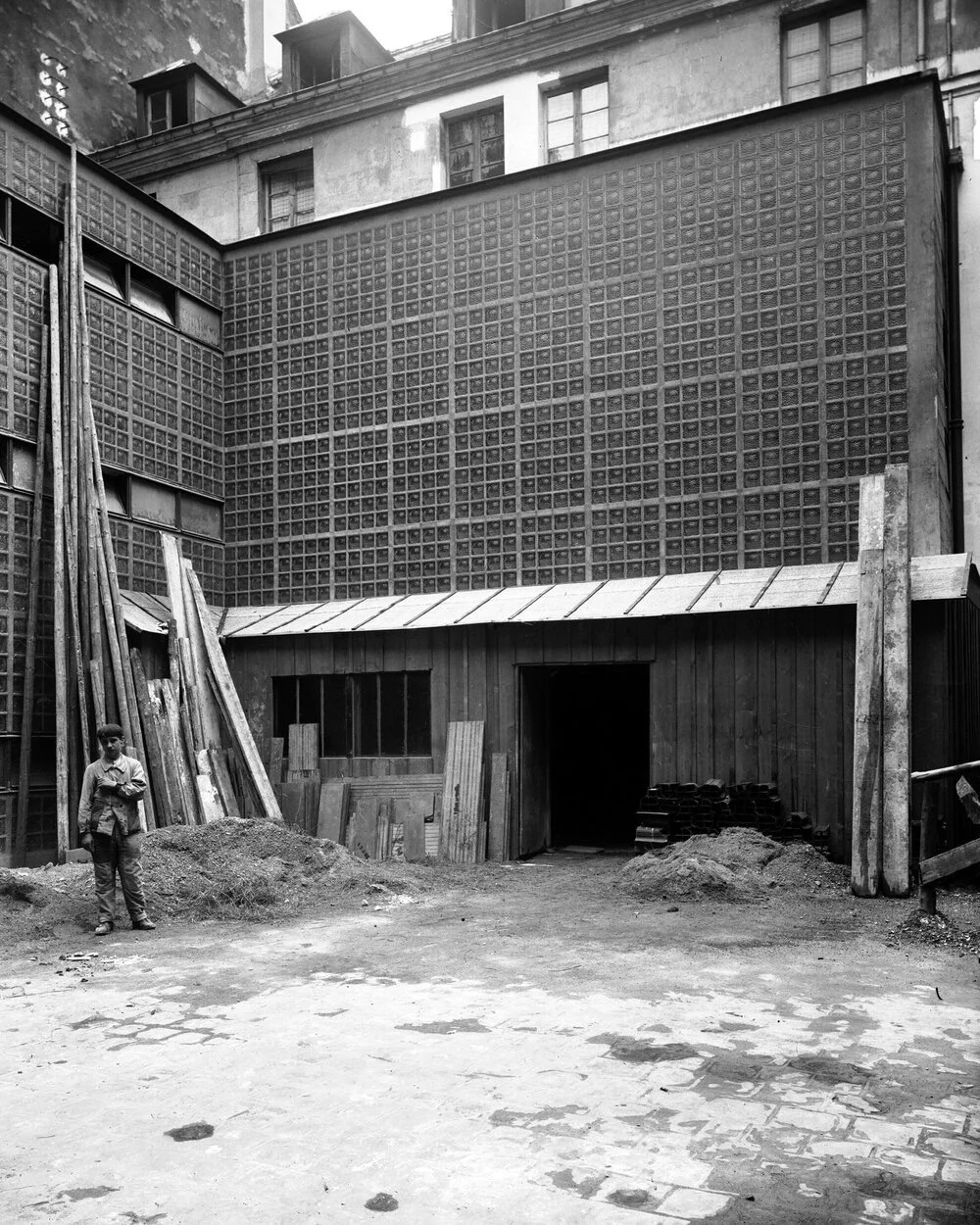

The glass block facade of the now iconic Maison de Verre, Paris, under construction (1932), designed by French architect Pierre Chareau

A dish of Fruit and Peach Blossoms, in jade and various stones, including amber, glass, bone, and feathers, Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

From almost the beginning of twentieth century minimalism and simplicity in interiors became a token signifier of privilege and wealth. In 1925 after dining at the Saint-Germain apartment of French decorator and doyenne of reductive elegance Jean Michel Frank (1895-1941) (which has since been masterfully re-imagined by interior architect Pierre Yovanovitch), artist Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) wrote to a friend, “Very charming young man, pity the burglars took everything he had!” Frank designed for an elite international clientele and made a name for himself creating austere, airy, uncluttered interiors that by the mid-1920s were considered to be the epitome of chic. Yet, for some patrons at least, the sort of monastic severity Frank favoured would prove a step too far. French novelist, dramatist critic and poet François Mauriac (1885-1970) recalled the designer was “willing to decorate our new apartment so long as we agree to get rid of most of our furniture”. Of the finished result Mauriac lamented its spartan, minimally furnished appearance; complaining that he could no longer find his bearings, that “it is cold” and “sad”, “in the taste of the abbey cell of a monk,” grumbling long after completion that, “this century will be known for inventing ruinous poverty”. Of course, there was also a socio-political aspect as to why the wealthy suddenly desired simplicity; by the mid-nineteen-thirties the devastating effects of the 1929 Wall Street crash were being experienced first hand in interwar Europe and even the haute bourgeoisie felt the pressures of a new age which called for simpler and more affordable furniture; and for the most part the affluent classes — who during the golden age had commissioned entire suites of furniture — were no longer capable of supporting their former lavish lifestyles. Le Corbusier (1887-1965) declared that “A house is a machine for living in,” and in response to prevailing trends, architects like Eileen Gray (1878-1976), Jacques Adnet (1901-1984) and Pierre Chareau (1883-1950) designed furniture from glass and steel which, although far less expensive than the labour-intensive extravagances of Art Deco, remained true to the sort of high-quality craftsmanship with which French decorative arts had become synonymous. Such furniture and interiors were essentially a precursor to an aesthetic that would become known as the “International Style” — as personified perfectly by American architect Philip Johnson’s 1949 “Glass House” in New Canaan, Connecticut; an exercise in acerbity, the 1,800-square-foot-dwelling, entirely clad in glass, has since been described by the New York Times as “the world’s most famous transparent box”.

An aspirational interior typical of the sort featured in Kinfolk magazine, with white walls and an abundance of raw, natural materials

In recent years, of all the glassy, white-walled, gallery-like spaces to grace the pages of glossy magazines, the California estate of reality TV star, acolyte of pop culture and recently anointed “fashion icon” Kim Kardashian West (b. 1980) is perhaps the most gossiped about; after seven years work a triumvirate of super-star designers — Axel Vervoodt (b. 1947) Vincent Van Duysen (b. 1962) and Claudio Silvestrin (b. 1954) — transformed what had formerly been a relatively nondescript suburban McMansion into a “futuristic Belgian monastery” (as described by Kim’s former husband Kanye “Ye” West (b. 1977) in a 2020 interview with Architectural Digest). Its interiors are an ode to sparsely decorated intentional emptiness, with furniture and lighting by Pierre Jeanneret (1896-1967), Serge Mouille (1922-1988) and Jean Royère (1902-1981), as well as a blue-chip art collection of works by such illustrious names as Vanessa Beecrofall (b. 1969), Anish Kapoor (b. 1954) and Isabel Rower (b. 1998), scattered like breadcrumbs across 4,000-square-feet of Venetian plaster and bleached Dinesen flooring. Yet despite the prevailing trend for neutrality and wabi-sabi aesthetics, the New York Times recently declared that “fake food is trendy again” and maximalism is back with a vengeance; this is apparently as a result of months of intermittent lockdown induced incarceration, as well as supply-chain shortages, which have led us all to reassess the relative merits of living in artfully curated “minimalist” interiors, devoid of the clutter and detritus of everyday life.

The desire for mid-century furniture, linen bedsheets and fiddle-leaf figs has given way to trends like “cottagecore” and “grandmillenial”, the aim of which is to elevate tasteless, chintzy tat into a desirably kitsch interior; something which by and large the UK interiors industry is perfectly placed to tackle head on. This maximalist resurgence apparently encompasses the desire to employ fake food, for e.g. resin-cast croissants and charcuterie-shaped candles as objets d’art. Retro-style fake cakes are now big business on Instagram with artist Leanne Rodriguez, also known as Elrod, selling luridly coloured “Jello mould” lamps and “parfait sculptures” for anywhere between $100 and $3,500 (there’s even a “Chipped Beef Aspic Lamp” for those in the market for something more savoury). The penchant for using fake food pieces as decoration is of course nothing new; as early as the sixteenth century trompe l’oeil majolica took the form of fruits, nuts and vegetables (there are even examples of Chinese Qing dynasty, Jiaqing period (1796–1820) fruit, artfully rendered in jade and alabaster), and then in the 1950s and 60’s it became something of a mid-century trend. “Blown glass fruit was super popular in the 50s and 60s, especially after the Second World War when it was more affordable and kind of interesting or enticing for middle class Americans to travel abroad to Italy,” explains Sarah Archer, author of The Midcentury Kitchen, “It kind of represents domesticity and a certain middle class effort at beautification, but it’s also kind of tacky at the same time.”

Philip Johnson’s 1949 “Glass House” in New Canaan, Connecticut, demonstrating an aesthetic that became known as the “International Style'“

Maximalist interiors, full of scallops, fringes, heavily patterned wallpaper and kitsch objet d’art are undoubtedly an editorial godsend; after all, such eye-catching, colourful spaces make for attention grabbing magazine covers, screaming and shouting from the shelves of newsstands and jousting for attention amongst their often more demure competitors. The reality is, however, that the sort of bland, Instagram-perfect, wildflower festooned interiors beloved by millennials are still the prevailing “trend” — where it’s all very beige and where there’s nothing offensive, nothing that hurts your eyes and nothing that stands out. It’s an interior obsession that over the past decade has been championed and defined in the sun-dappled pages of cult quarterly Kinfolk magazine — whose mascot ought to be a slice of avocado toast. Like all lifestyle publications, it traffics in aspiration, showing its avid readers how to express their creative identities through a well-edited table-scape, a plate of heirloom vegetables and a house full of Hygge-y, folk-y wooden-ish things (indeed it’s a look that has become so ubiquitous that website Kinspiracy collected copycat images from Instagram and published them beneath the tagline “Kinfolk Magazine: Making White People Feel Artistic Since 2011”).

The sort of hyper-curated minimalism associated with art collectors and celebrities has long been seen as nothing more than and elitist class signifier — another form of conspicuous consumption, i.e. “Look at me! Look at all of the things I have refused to buy, and the incredibly-expensive, sparse items I have deemed worthy instead!” To an extent, Kinfolk can be seen as part of the long line of minimalism responding to consumerism, for e.g. the egalitarian, populist ideals of French modernists such as Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) and Jean Prouvé (1901-1984) who were reacting to the maximalist excesses of the Parisian haute bourgeois. We now live in an age where increasingly cheap mass-production has made both maximalism and minimalism available to the average consumer. This might seem at first blush like democratisation of interiors, but in reality it only serves to fan the flames of consumerism, as whichever “trend” you choose, there’s inevitably a high-street store willing to sell you the mass-produced tat necessary for achieve it. As with all quick trends and fast fashions, it would be far better if they were ignored entirely, and that people thought sustainably, with a view to buying things that are made to last, or even better, second-hand, antique or vintage, so as to avoid the ubiquity of magazine-led-interiors.