Poetics of Light

Ingo Maurer

“Light is a very flexible material where often we don’t even know if it exists or not. Research in a field like this never ends. As a designer I have always sought emotional satisfaction, above any other factor. That is the key to my work, but I live it as an intuition rather than a duty” — Ingo Maurer

Regarded as a pioneer in the development and use of the latest lighting innovations, Ingo Mauer (1932-2019) is perhaps unmatched in the breadth of materials employed in delivering witty, conversational luminaire and light designs. He fashioned lamps out of shattered crockery, scribbled memos, holograms, tea strainers and incandescent bulbs with feathered wings. He was fascinated by Thomas Edison and the prototypical light bulb, which he saw as manifesting “the perfect meeting of industry and poetry”. Yet, in spite of a reverence for his forebears, Maurer’s exploration and acceptance of emerging technologies and the ways in which they could be employed, led him to reject traditional notions of the lamp as merely an object that gives us light. Mauer stimulated imagination and excited emotions in a way that gave him a reputation as a poet of light; achieving artistry from an immaterial medium and imbuing spatial environments with drama and a sense of ephemerality. The first lamp he designed in 1966, Bulb (his product names would, over time, become more nuanced) was an outsized bulb-shaped glass sleeve enclosing a functioning incandescent bulb. A combination of industry and poetry born from the idea of the simple archetypal form it won high praise from the designer Charles Eames and in 1968 became part of the Museum of Modern Art’s collection in New York. “The Italians even thought he was Italian,” said Mariangela Viterbo, the head of a public relations firm in Milan, who met him in the late 1960s when he presented Bulb at a trade show in Turin. “In that period the big vision of modern design was Danish or Finnish. Ingo came with something more similar to our temperament — more ironic, more joyful. It made a difference.” “Bulb” was the start of a continuous flow of endlessly inventive creative work that was witty and questioning, but above all beautiful. “He loved the technology that was coming out, but to him it was like Houdini,” said his long-time friend Kim Hastreiter, the co-founder of Paper magazine. “He used the technology in his lamps like a magic trick.”

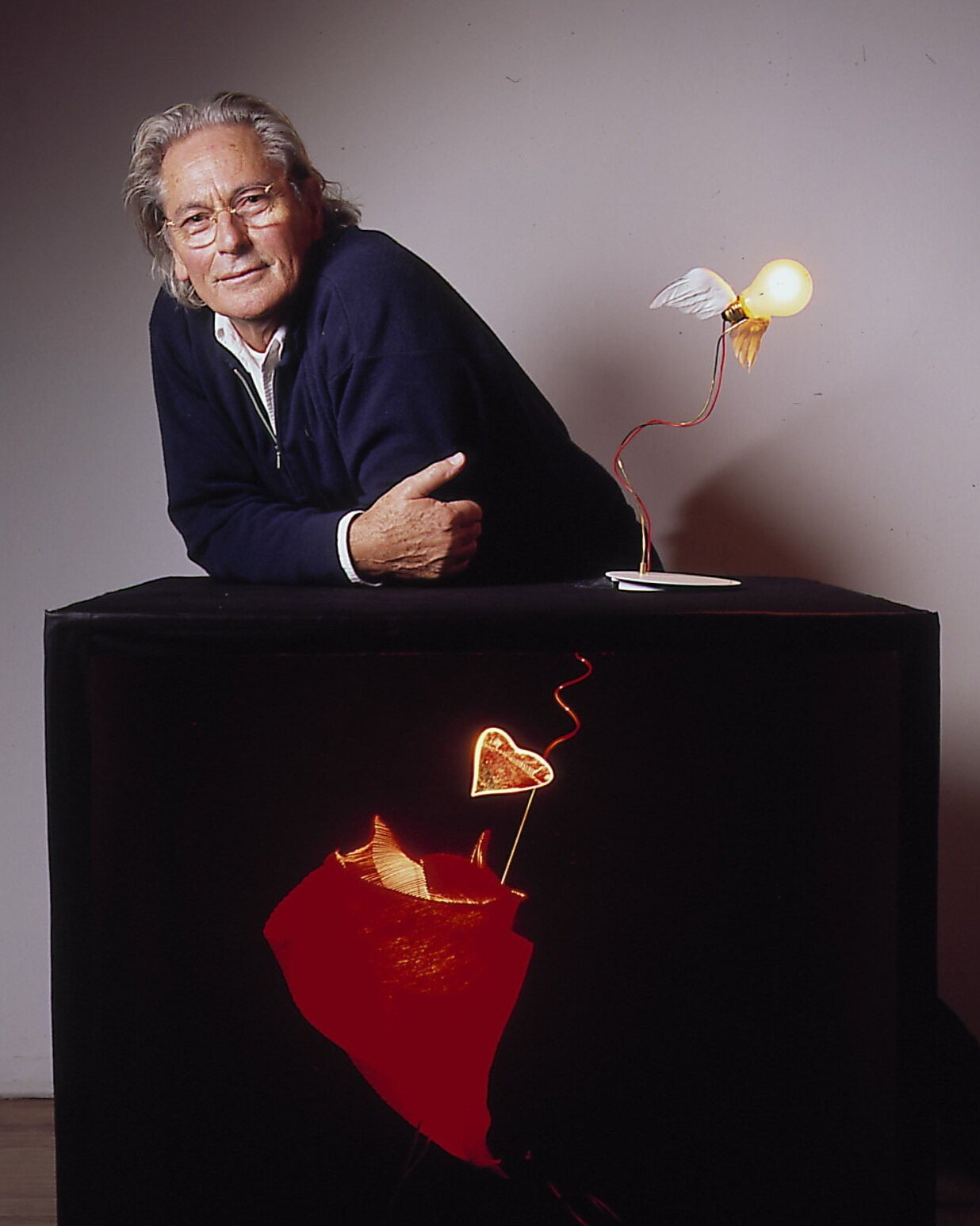

Ingo Maurer in 1998 with two of the many artful lamps he created

Platform at Westfriedhof subway station, Munich (1998) one of the many civic projects executed by Ingo Maurer GmbH

The son of a fisherman, Maurer was born and grew up on the island of Reichenau in Lake Constance, in southern Germany near the Swiss border. He later recalled how his passion for light was born from some of his earliest memories of fishing and seeing the reflection of light play off the surface of the water. Maurer lost both his parents at a young age and his brother, the eldest of his four siblings, ordered him to leave school and find work. He could apprentice, he was told, either as a butcher or as a typographer at a newspaper in Munich. He chose the latter. Though it wasn’t an obvious career path for a lighting designer, it was a formative experience that attuned his eye to precision and the notion of visual poetry in the everyday. “Well, if you add certain letters, A, B, C and so on,” he said, “you have space in between, and that for me makes also light, really”. In 1960, Maurer travelled to the United States with his German girlfriend, Dorothee Becker, working in New York and San Francisco as a freelance graphic designer. It instilled in him a romanticism for the “land of opportunity”, and a fondness for the big, bold, brash, cartoon images of New York’s emerging Pop Art movement. It was during this time that he had the idea for his 1966 Bulb lamp, an early example of his ability to transform and reinvent the everyday object (and one of the many references to Edison that he would produce over the years), that proved such a terrific success that Maurer was able to forge for himself an entirely new career.

His lightbulb moment came, as it were, while on holiday in Venice. After a boozy supper, he went up to his room and lay down on the bed, gazing up at the ceiling fixture overhead; the naked, incandescent light bulb drilled into his eyeballs. “It was like a ... coup de foudre! Still half drunk, I drew a sketch of a lamp,” he said. “The next day I travelled to Murano with this idea in my pocket. When I got home, I designed a base made of pressed metal to go with it: the Bulb lamp was born!” He returned to Munich as a newlywed, to found his own company, Design M — which was later renamed Ingo Maurer GmbH — to produce his now iconic luminaire, as well as a wall storage unit called “Wall-All” invented by Becker. At that point in time, Maurer placed a great emphasis on the form of an object, similar to great Italian designers like Achille Castiglioni (1918-2002) and Vico Magistretti (1920-2006). In the 1970s he was looking for something that would produce a soft glow “a warmer, more eye‐pleasing light”. In Paris, Maurer found what he was looking for — bamboo and lacquered rice-paper fans. Later that year, while in Japan on business his search for a fan source was frustrated. “Plastic had replaced natural materials, even in fan factories,” he recalled. A year later, on the island of Shikoku, he sought the tutelage of a great master of fan-artistry Shigeki-san: “Even though we couldn’t talk to each other, there was an amazing intuitive understanding between us. This is how I slipped into Japanese culture, and that brought me even closer to the topic of light.” Maurer went on to develop his extraordinary collection of Uchiwa fan lamps, crafted according to traditional Japanese methods in bamboo and lacquered rice paper; the most spectacular of which was a seven foot tall floor lamp.

Quick to embrace new forms, Maurer was one of the first to experiment with the formal possibilities of halogen; for his 1984 YaYaHo, he fashioned a lamp in the form of parallel low-voltage wires draped with shaded halogen bulbs that dangled like jewellery. As a designer Maurer took inspiration from what he saw around him. “First, the idea of an object arises in my head — like a dream,” he said, describing his creative process, “only in the next step I search together with my team for ways for the realization. Sometimes it takes decades until the technical developments make our imagination possible.” The idea for YaYaHo came to Maurer after he spent a New Year’s Eve in Haiti; as he left a nightclub at dawn he saw a naked light bulb, soldered directly to an overhead power line, forming an unauthorised street lamp. After four years spent tinkering in his workshop, Maurer perfected a system of adjustable lighting elements with halogen bulbs hung on horizontally fixed metal cables. Rather than a conventional lamp, it was a system of parts (including a transformer, a pair of cables, and a range of different lights and reflectors) that could be tailored to a specific space, adjusted, reconfigured and customized into varying compositions. It represented an entirely new aesthetic approach, almost ethnographic in that the user, in effect, became the designer.

Black “Bellissima Luzy” light (2018) designed by Ingo Maurer

In 2001 he made an early desk lamp using LEDs (EL.E.DEE) then created a wall made of circuit boards and LEDs in a pattern that resembled a wallpaper (Rose, Rose on the Wall). Some of them were made with artisan methods, such as Zettel’z (1997) and MaMo Nouchies (1998), part of a series in Japanese paper (the limited edition Zettel’z Munari, created with Bruno Munari’s iconic alphabet series, whilst reminiscent of a children’s room, speaks of an originality and creative spirit that permeates his oeuvre, and is so much more than mere childish fancy). In 2005 he embedded wafer-like organic LEDs in glass table tops, creating starry clusters with no visible connections. In 2012, he collaborated with Moritz Waldemeyer, another German designer, to produce a narrow table lamp with 256 LEDs simulating flickering candlelight (My New Flame). He also made the bizarre range of Bellissima Luzy lamps, fashioned from plastic gloves with low-voltage frosted light bulbs at the fingertips. Weird and wonderful, it’s a design that bears no rhyme nor reason — because there’s no reason that it should. His melange of Marigolds-and-Yves-Klein-International-Blue is exemplary of the liquidity of Maurer’s design process; initially creating an installation of dyed blue sponges, he was amused by the line of paint spattered gloves hung up to dry in the studio at the end of each day. Staring at them hanging there “it was more than whispering to be a lamp, it was blaring it out!” Maurer recalled, and so, he decided to appropriate it into his aesthetic. Mauer continually explored other kinds of light source, from halogen to light emitting diodes, but he would never renounce the old-fashioned simplicity of an incandescent light bulb. With Lucellino (the name a play on words from the Italian “luce” (light) and “uccellino” (little bird)), he attached hand-made goose-feather wings and suspended the bulb like a hovering Cupid, and with Wo bist du, Edison ... ? (“Where are you, Edison?”) a 360-degree hologram of a light bulb appears as if suspended in the center of an acrylic cylinder.

Maurer was driven by a desire to go further than producing conventional industrial objects. He began to work on ambitious civic and private commissions, from the platform at Westfriedhof subway station, Munich, to a sushi bar designed by Shiro Kuramata in Tokyo, lit by a line of Maurer's paper-shaded lamps. A crowning moment of disruption occurred at the 1994 Euroluce lighting fair in Milan, where Maurer introduced a chandelier made of a carefully assembled explosion of porcelain crockery fragments and flying cutlery. The fixture was initially called Zabriskie Point, as he was reminded of an explosive slow motion scene Michelangelo Antonioni’s film of the same name. An Italian visitor to the fair proclaimed, proclaimed “Porca Miseria! Che fantastic, Ingo! Tu sei pazzo, geniale!”, a phrase that translates roughly as “Dammit!”, and thus the abiding title of the work was born. Although several Porca miserias! are still made by hand, each year, Maurer was never comfortable with the high price tag (upward of £30,000, as quoted by at least one website) and so he donated some of the profits to a family he once met in Aswan, Egypt.

Maurer also created large scale light installations, for example for Issey Miyake’s 1999 fashion show in the Parc de la Villette and the atrium of Lafayette Maison in Paris. He was also asked to create special YaYaHo installations for the exhibition Lumières: Je Pense à Vous at Centre Georges Pompidou, in Paris, in 1985, the Villa Medici in Rome, and the Institut Francais d’Architecture in Paris. At Estúdio, Maurer’s “Golden Ribbon”, a double sheet of metal, twisting elegantly, letting light pass through its cracks, traversed the space above his broken egg lamps. For his 2016 Glow, Velasca, Glow! he made Milan’s Torre Velasca tower (designed in 1952 by the influential Italian architecture firm BBPR) appear as if it was glowing from the inside. In 2009, when EU regulations stopped production of frosted halogen bulbs, as a protest, Maurer launched “Euro Condom”, opaque condoms that fit over clear incandescent bulbs —which were not affected by the guidelines — to give a similar effect to the banned bulbs. At Maurer’s annual party during Milan design week, his “Birds Birds Birds” chandelier defiantly flew in the face of the ban, with each its 24 opaque bulbs cloaked in a condom.

Porca Miseria! (“What a Disaster!”), ceiling light (1994), by Ingo Maurer

Despite the unusual materials Maurer employed, throughout his career, he professed to be more interested in the medium of light itself. I’m very lucky to work with the material which does not exist,” he said in 2017 on a podcast produced by Arkitektura. “I can not take it in my hand, and bend it, and look at it from different sides”, he explained; light is not a thing, he said, but “the spirit which catches you inside.” Of course not everyone was charmed by his antic designs. Reviewing a 2007 retrospective of Maurer’s work at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in Manhattan, the art critic Ken Johnson wrote in The New York Times, “While some of his pieces are lovely to look at, his work in general is so precious and so busily eager to please that it will make you pine for the reproving austerity of the fluorescent-light Minimalist Dan Flavin.” Paola Antonelli, the senior design curator at the Museum of Modern Art, disagreed: “I’ve never seen anyone experiment with such abandon,” she said, “and experimentation is the opposite of wanting to please.” Antonelli provided Maurer with a showcase in 1998, when she included his lamps in a design exhibition, and hung “Porca Miseria!” in in “Energy” (2019).

“The biggest setback for me is that I haven’t lived a private life. My work has been my life and my passion.” — Ingo Maurer

His final installation, a sweeping chandelier made of more than 3,000 silver-plated leaves, was completed in Munich’s Residenz Theater just days before his death. Describing his beginning, always, with light first and form second, Maurer was known for his creativity and constant reinvention. He took joy in experimenting with a whimsical approach, and throughout his career he was celebrated for designing minimalist, iconic, and at times wholly irreverent luminaires. The subject of numerous solo exhibitions, his work defied categorization, integrating a broad spectrum of materials and in some cases, introducing new typologies. Maurer produced over 120 product designs over the course of his prolific career; winning a slew of accolades, from the Compasso d’Oro to the Design Prize of the Federal Republic of Germany, as well as the title Royal Designer of Industry, which he was awarded by the British Royal Society of Arts. “My perception of light is so strong and distinctive, almost an obsession,” Maurer said in a 2007 interview. “This forces me to continuously play and experiment with the reflection and the art of light.” What fascinated Maurer was light itself; he used everything from paper and textiles to mirrors, feathers, ceramics and found objects to diffuse and celebrate light. His works were based on the concepts of surprise and disorientation. They represent those moments of pure fantasy that most of us experience, but dismiss, or confuse with asininity. At one of his design events at Krizia space in Milan Maurer handed out paper 3-D glasses that created a vision of hearts in each spot of light, “That was so him,” Antonelli said of his whimsy. “In a pair of throwaway glasses.”