Acts of Daring

Georges Jouve

“Deal with nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone, all placed in perspective, so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point. Lines parallel to the horizon give breadth, a section of nature, or if you prefer, of the spectacle spread before our eyes by the 'Pater Omnipotens Aeterne Deus'. Lines perpendicular to that horizon give depth” — Paul Cézanne

Originating from, and composed entirely of the soil, pottery it is often seen as the most humble of materials. Yet at their best, potters are able to perform alchemy on clay, transforming earth and water into an expression of artistic organic form. Georges Jouve (1910-1964), widely acknowledged as one of the most important ceramicist of the immediate post-war period, was an expert in this regard. A highly skilled and virtuoso potter, Jouve modernized the art of ceramics, developing unique techniques motivated by his individual style of sensual and sometimes ironic creations that illustrate a subtle combination of rigor, savoir-faire and imagination. Jouve made no distinction between use, utility and decoration, producing sculptural ceramics for modernist interiors, and in doing so, creating an extraordinarily varied language. He was able to convey a breadth of emotions and themes, from humour, to quiet ageless solemnity, his works extending in range from popular imagery — sometimes verging on kitsch — to classical sobriety. His rigorously simple ceramic forms, soft and playful, include plump, contrapposto vessels, shiny, enamelled, cylindrical vases, and glazed ceramic pitchers, bulbous and rotund. Tireless experimentation with glazing and firing techniques led to a palette of perfect matte blacks and bone whites, interspersed with bright cheery splashes of lime green, lemony yellow and selenium red.

Untitled, glazed stoneware, cast stone (1959) by Georges Jouve Photograph: ©WrightAuctions

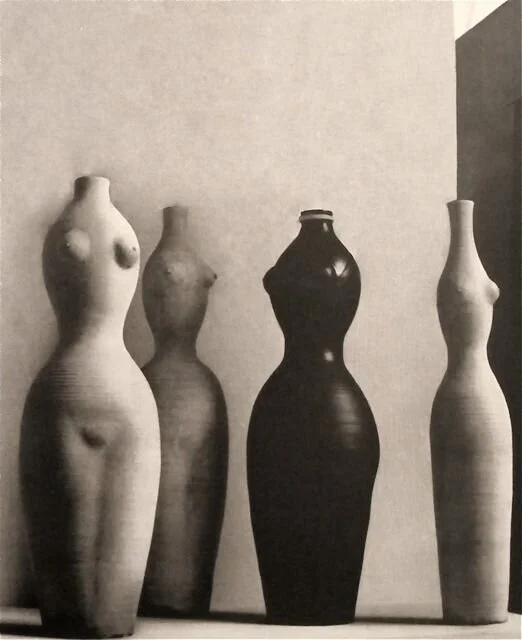

Ceramics by Georges Jouve at a collectors home in Paris

Born in 1910 in Fontenay-sous-Bois, France, an eastern suburb of Paris, Jouve had a predisposition toward art and enrolled at the prestigious École Boulle in Paris where he received both theoretical instruction in Art History in addition to his technical studies as a sculptor. After Graduation in 1930 he completed courses at Académie Julian and Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Following his formal education, after a short period of training in an architectural firm, he embarked on his artistic career as a theatrical set designer. However, his ambitions were interrupted by the outbreak of the second world war when in 1939 he was drafted into the army. Taken prisoner by German troops, Jouve was interned in a concentration camp. Following several unsuccessful attempts, Jouve escaped and took refuge for the rest of the war at his step parents’ home in Dieulefit, a potters’ village in the South of France where the Vichy government had established a “Free Zone”.

Ceramics by Georges Jouve

Femme à nichons, vase, glazed stoneware (1948) by Georges Jouve Photograph: ©WrightAuctions

Drawing on his technical studies as a sculptor and the influence of the area — known since its antiquity for its ceramics tradition — he began making pottery works, adopting vernacular forms with a traditional galena, lead-based green glaze. He created decorative objects modeled in clay and inspired by the Southeastern French potting traditions of ceramic religious objects. This early influence accounts for the elegant, curving forms which are predominant throughout his pieces. For Jouve, matter never took precedence over form. Like Cézanne, he believed that everything in the world was composed either of a sphere, cone, cylinder or cube. It was through this rigorous approach that Jouve bypassed anecdote, did away with figural representation and achieved a universal expression.

Jouve took traditional notions of ceramics and turned them on their head; approaching his work as an ongoing journey of creation, he was able to transform the very nature of the medium, raising its status in the pantheon of the arts. Selling his work through both local and Parisian galleries, Jouve soon garnered the attention of famed modernist designer Jacques Adnet (1901-1984) who invited him to participate in the exhibition La Ceramique Contemporaine organized by the Compagnie des Arts Francais (“CAF”) where his creations first reached a broad audience. Founded by master ébénistes, Louis Süe (1875-1968) and André Mare (1885-1932), CAF catered to an international clientele of the intellectual and artistic elite.

Jouve returned to Paris after the Liberation where he opened an atelier for ceramics on the Rue de la Tombe-Issoire, and began creating ceramic vases, lamps, and tables for his growing clientele. He favoured rich tones — which he achieved through the use of matte enamel glazes — and employed a simple, but vibrant, palette of deep red, orange, yellow, white, and black; comparable to the decorative lacquer-ware of Eileen Gray (1878-1976), who was also working in Paris at the time. Along with Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) and Jean Prouvé (1901-1984), he demonstrated a willingness to open up the decorative arts to a wider audience. Jouve's ceramics echo the organic modernism of his CAF colleagues, many of whom he went on to collaborate with, such as Paule Marrot (1902-1987), Serge Mouille (1922-1988) and Mathieu Matégot (1910-2001).

Running a wide gamut in style — from monochromatic and minimalist vessels to whimsical and colourful figurines — Jouve’s works were at the forefront of French ceramic artistry. While the colour palette of the post-war era was often bold, Jouve exercised restraint, creating pieces that were simple, one colour – often black – forms, which he imbued with a metallic dazzle and depth: “black is a colour”, said Henri Matisse (1869-1954) in that same period.

Although much of his early work was figurative, adopting animal or human shapes, there was one area in which Jouve shone brilliantly, and that was in the creation of form itself. He produced wonderfully biomorphic, organic shapes; in his most soaring examples from the 1950s and 60s, we see a simplifying abstraction, with familiar forms adopting exaggerated proportions, at once inventive, playful and disciplined. Embodying a strong, sensuous aesthetic, their rounded shapes and smooth surfaces seem almost like acts of daring. The asymmetrical nature of these pieces, which can be attributed at least in part to Jouve’s interest in Japanese culture and aesthetics, was intended to express the ever-changing reality in which we live. His glazes, often dense with opaque colour, were chosen to compliment, rather than compete with, his abstract ceramic forms. Whilst his use of cracked enamel is emblematic of what the decorative arts owe to formal research over the first half of the century in surrealism and cubism. Whether as a expression of simple creation in his sculptures to the more everyday objects like coat racks and ashtrays, the line of a Jouve piece is unmistakable.

Jouve continued to exhibit in numerous “Salons” in France and internationally: Salon des Artistes decorateurs in Paris, Association Francaise d'Action Artistique in Rio de Janeiro, and Vienna, Toronto, Rome and Cairo. He relocated again in 1954 to Aix-en-Provence, just north of Marseille and the Mediterranean coast. He would continue to work there until his untimely death in 1964, leaving behind a ground-breaking oeuvre, its biomorphic sculptural idiom, wholly redefining the craft.