Does Exclusivity Matter?

the Lure of the UNATTAINABLE

“There’s no fun in a bag if it’s not kicked around so that it looks as if the cat’s been sitting on it — and it usually has. The cat may even be in it! I always put on stickers and beads and worry beads. You can get them from Greece, Israel, Palestine — from anywhere in the world.” — Jane Birkin

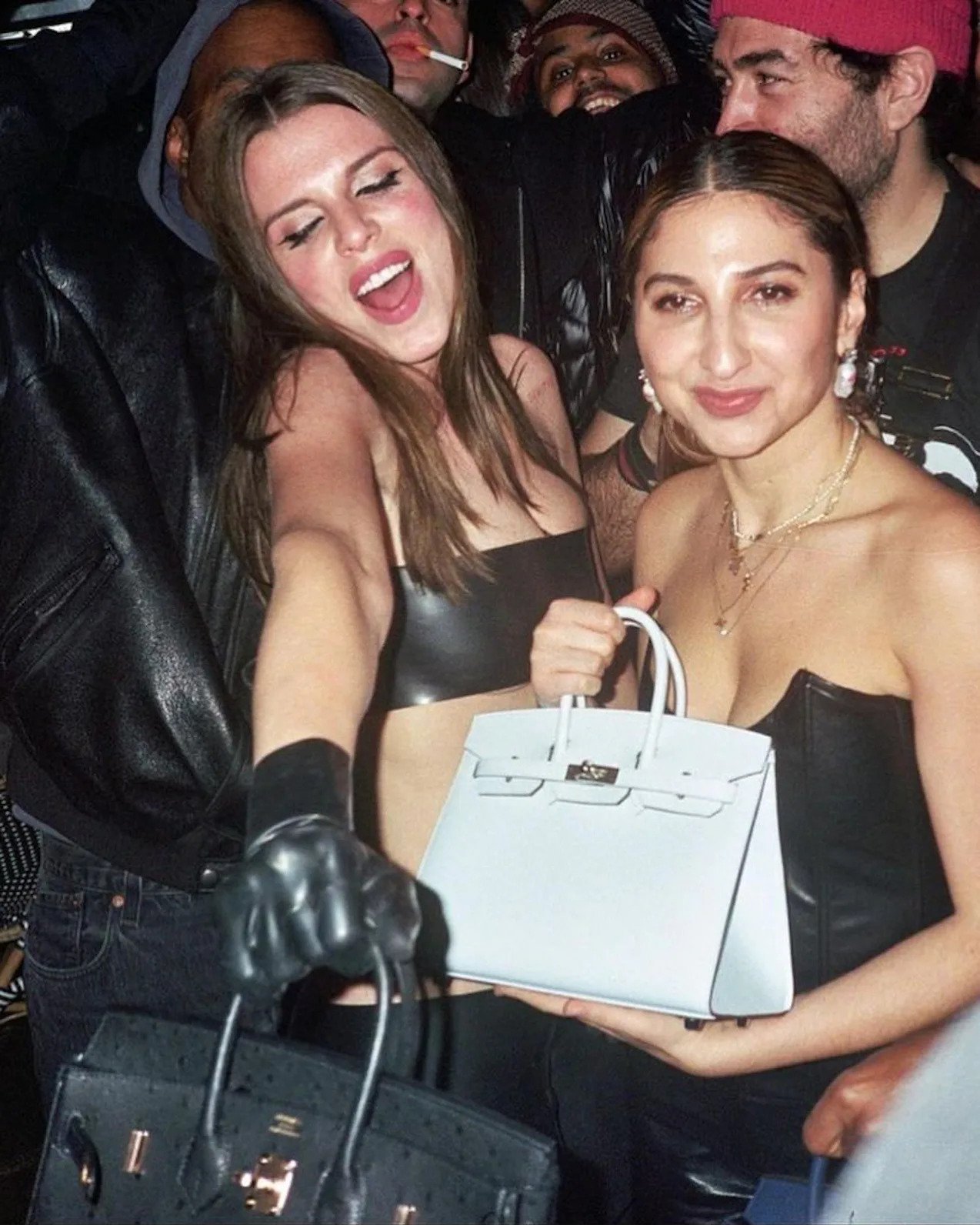

It’s an immutable facet of human nature that we want what we can’t have, and since the advent of consumerism in year dot, such desires have been mercilessly exploited by marketing and advertising supremos as a means of luring in a loyal customer base. In terms of the luxury sector, this has traditionally been achieved through price point, whereby, if something is seen as unaffordable, or unattainable, often accompanied by a suitably long waiting list, people will desire it all the more; the key example, perhaps, being the Hermès Birkin, a bag, which since its release in 1984, has never lost its inherent charm, becoming increasingly sought after by an ever-expanding nouveau riche. This is a phenomenon preserved for posterity in Season 4 of the prime-time TV show Sex and the City, when fictional PR guru Samantha Jones (played by Kim Cattrall (b. 1956)) pines after the cult carryall to the extent that it loses her a celebrity client. Upon entering the brand’s Manhattan outpost, with the objective of shelling out on the much lusted-after leather tote, Jones learns there’s a five-year waiting list: “For a bag?” she asks, aghast. “It’s not a bag, It’s a Birkin”, scoffs a suitably haughty sales rep (though now, of course, she would have been put on a waiting list by an iPad-wheeling “greeter”, just for the pleasure of entering the store). With the objective of jumping the queue, Jones namedrops her latest client, Charlie’s Angel’s star Lucy Liu (b. 1968), which seems to have the desired A-list effect. Much to Jones’ chagrin, a few days later Liu shows up at lunch toting the cherry red object of her desire. “Some nice man dropped it off at my hotel this morning,” she shrugs. “It’s not really my style, but hey it’s a free bag.” Jones tries to explain, but unimpressed, Liu fires her, leaving bag in hand, like a latter-day Aesops Fable for a materially driven, label-obsessed society. It may have been almost a decade ago, but when it comes to status bags, the Birkin is still, indisputably, the most coveted — becoming a must-have collectable for the super-rich and celebrities alike; former Spice Girl turned fashion designer Victoria Beckham’s (b. 1974) carefully curated collection of more than a hundred Birkins, including a £100,000 shocking pink version, is said to be worth somewhere in excess of £1.5m. Indeed despite the current cost of living crisis, the venerable French fashion house recently reported a 23% jump in sales for the first three months of the year, with demand being such that it plans to open a string of “artisan” factories, doubling the size of its workforce, so as to keep up with spiralling orders. This is apparently something not lost on the scriptwriters of Sex and the City reboot And Just Like That — where, in the forthcoming second season, Carrie Bradshaw’s high-powered real estate broker (played by Sarita Choudhury (b. 1966)) falls victim to a callous purse-snatching — having her orange, ostrich leather Birkin 35 (the same model can currently be found on e-commerce platform 1stDibs for an eye-watering £53,000) torn from her elegantly manicured hands, leaving her Fendi caftan flapping, as in six-inch strappy sandals she mounts a somewhat futile pursuit.

Actress Julia Fox sporting her Hermès Birkin, which, supposedly, the victim of a machete attack, has been dubbed “the ultimate distressed Birkin” by W Magazine, photograph: Instagram/@juliafox

A festival-goer sporting a t-shirt from the “Mickey Mouse x Supreme” collection, a brand that once captured the countercultural zeitgeist, photograph: Getty Images

Of course, this is a trend by no means exclusive to one-percenters and outside the traditional worlds of luxury fashion and haute couture, a much newer phenomenon has, in recent years, taken hold, with brands such as Anti Social Social Club (“ASSC”), Stüssy and Supreme creating a market for hype streetwear. Yet, for Supreme — who, up until recently, had been considered the coolest clothing company on the planet — the tides are, seemingly, turning. For those unfamiliar with this particular fashion subset, on “drop days” (Thursdays at 11 a.m. Eastern) the brand’s “Box Logo” t-shirts and hoodies, as well as homewares and high-profile collaborations with long-established brands such as North Face and Nike would sell out, quite literally, within milliseconds. Securing a $40 T-shirt required the dexterity of a virtuoso, so as to key in a credit card number quickly enough to beat throngs of fans and “hypebeasts” all desperate to snag the latest must-have. Throughout the twenty-tens, Supreme was, undoubtedly, the most powerful brand in youth culture with “merch-crazed” fans devising bots to “auto-snipe” coveted drops — immediately re-sharing images of themselves wearing the spoils of victory on Tumblr and Twitter. The hysteria was such, that in 2020 venerable auction house Christie’s presented Behind the Box: 1994-2000 an entire sale dedicated to the billion-dollar streetwear brand, curated by none other than “renowned Supreme historian” Ross Wilson, and “sourced from the vaults of some of the world’s most prominent collectors”. This included 21-year-old Canadian student James Bogart’s collection of every retail-released Supreme Box Logo T-shirt produced since the brand’s inception in 1994-2020, which was expected to sell for around US$2 million (an estimate based on a 2018 collection of 248 Supreme Skate Decks that sold for $800,000 at auction with Sotheby’s). The Box Logo tee, Christie’s in-house specialist Caitlin Donovan explains, is the “most recognizable, sought-after article of clothing streetwear has ever seen,” which is why, apparently, this particular assemblage of branded merch was seen to be “the most powerful, culturally significant contemporary collection streetwear has to offer”.

A collection of every retail-released Supreme Box Logo T-shirt produced since the brand’s inception in 1994-2020, expected to fetch US$2 million at Christie’s “Behind the Box: 1994-2000” sale in 2020

The landmark sale came at an interesting time for Supreme which had recently been acquired by VF Corp (parent company of Vans, The North Face and Timberland), in a deal that valued the company at approximately $2.1 billion. Now, perhaps somewhat unexpectedly, blogs, forums, Discord groups, Instagram commenters and TikTokers are all declaring Supreme dead. Twenty-seven-year-old streetwear enthusiast Nick Thommen has run Supreme Community, one of the largest dedicated fan pages for the past decade; the website tracks sell-out time of Supreme drops and in recent years he’s seen figures tick up from seconds to hours, and now even days (similarly, weekly “droplist” rankings, that at one stage attracted tens of thousands of votes, now draws in only a couple of thousand max). Supreme and North Face’s Spring/Summer 2023 collection, typically one of the hottest drops, sat online for days; a big deal to the label’s legions of loyal collectors and resellers, with sudden accessibility a sign Supreme might not be as desirable as it once was. “I think it lost some kind of coolness factor,” explains Thommen matter-of-factly, which, for a brand that trades on street cred, is clearly problematic. There is, arguably, a tripartite reason for Supreme’s crumbling grip on the streetwear zeitgeist: first, oversaturation has, essentially, made it far less exclusive, leading to a sharp decline in demand; in tandem, an over-reliance on its signature Box Logo and lack of any demonstrable innovation, in terms of new designs or concepts, has made the brand feel somewhat stagnant; combined with an increase in competition from an ever-increasing influx of hot new streetwear brands (such as Palace, Corteiz and Clints), has a resulted in a decrease in market share.

That said, whilst Supreme may no longer be the counterculture-defining juggernaut it once was, it’s by no means dead, in the sense of being irrelevant or unprofitable. Within the realm of streetwear “dead” simply refers to brands that have lost their clout, that aren’t as cool or hyped as their counterparts. Some have suggested that to remain relevant, Supreme needs to diversify, expanding its product line beyond clothing and accessories to furniture and homewares (bright red bouclé-clad Supreme x Pierre Paulin anyone?). One-time rival ASSC is no longer “cool” in the way it was half a decade ago, now owned by the same company that backs Ben Sherman and Martha Stewart (b. 1941) (indeed, in 2022 the American lifestyle queen and longtime, perhaps even OG, influencer, announced a collaboration with ASSC — in the form of a six-piece capsule collection, based around her love of food, featuring Stewart’s seductive oyster selfie, which, of course, sold out instantly, and, in hindsight, can be seen a precursor to her recent Sports Illustrated swimwear cover), and culturally-conscious types would, undoubtedly, consider it “dead”, but at the same time, somewhat paradoxically, it’s never been more visible, with drops selling out as quickly as they arrive. In the words of crooner Bob Dylan (b. 1941), times they are a-changin’, even if Supreme, a cultural touchpoint since the nineties, hasn’t really changed a great deal since then. “In the age of social media, it’s iterate or die,” explains Highsnobiety News Editor Jake Silbert, “and Supreme clearly has no desire to iterate.”

The Row co-founder Mary-Kate Olsen, carrying her beaten up Hermès Kelly, which, apparently, is set to be 2023’s biggest “trend”, photograph James Devaney/WireImage

Controversial style icon and pop parvenue Kim Kardashian (b. 1980) recently listed an alligator skin Hermès Birkin on KardashianKloset.com for US$110,000, resulting in outrage and ire from KUWTK fanatics, who felt she should instead have donated the high-end tote to charity. On a screenshot of the item shared to Reddit, fans wrote “How nasty! If that bag was in front of me it wouldn’t even impress me more than a purse less than $100,” with another adding, in similarly Shakespearean prose, “It’s crazy! Especially because the purse is kinda ugly lol”. This begs the question, are people buying the Birkin for its inherent aesthetics, or due to its price point and exclusivity? American entertainment website Animated Times recently ran the headline: “Jennifer Lopez Made $1.8B Rich Kim Kardashian Look Poor, Used Her Limited Collection $100K Hermès Himalayan Crocodile Birkin as a Casual Gym Bag.” Ergo, this once chic, understated carry-all, toted through the streets of Saint Germain by Saint Laurent’s (1936-2008) select coterie of muses, has, in the eyes of the masses, become as much a wealth signifier as a brash red Ferrari or gaudy diamond ring. Even the Van Cleef & Arpels clover collection and Cartier love bracelet (in terms of the latter, there are so many knock-offs the illustrious French jewellery house now refuses to authenticate them), once beloved by those “in the know” can be seen across the length and breadth of the Real Housewives franchise, stacked row upon row, demonstrative of how those items once considered “quiet luxury” (for which, see our recent article) can very quickly become as subtle as a “ludicrously capacious” Burberry check tote.

For even loyal customers, this can prove a sticking point, as, with negative market placement, the “Daniella Westbrook effect” can take the shine off even the most sought-after brands. For example, in 2014 multinational conglomerate Estée Lauder acquired haute French perfume house Frédéric Malle; once stocked only in independent boutiques and luxury department stores, its fragrances, which retail for upwards of £200, can be now found on the shelves of high-street department stores John Lewis and House of Fraser, within immediate proximity of songstress Ariana Grande’s (b. 1993) floral fruity fragrance “Sweet Like Candy” — which for some brand devotees has proved a step too far in terms of the democratisation of luxury brands. Conversely, a growing resale market, resulting in Hermès bags becoming available to a far wider audience, means to some, the more pristine the bag, the more gauche its wearer seems. “Real Housewives have closets full and that has a kind of tacky look,” explains Jenny Walton, an American illustrator and influencer who bought her second-hand Kelly at a designer consignment store. Similarly, The Row co-founder Mary-Kate Olsen (b. 1986), considered by a certain subset of upscale design-led hipsters to be the epitome of nonchalant cool, has an Hermès Kelly so faded its original colour is now difficult to discern. “Olsen has worn it universally everywhere: out and about in a pair of slacker sweatpants and in a fur jacket as she is grabbing a Starbucks coffee,” explains Liana Satenstein, Senior Fashion Writer at Vogue.com. “Though the bag costs upwards of $10,000, she treats it like the overstuffed briefcase of a used-car salesman.”

British actress, activist and Gainsbourg muse Jane Birkin (b. 1946), after whom the Hermès Birkin is named, has said of the pricey purse, “there’s no fun in a bag if it’s not kicked around”, photograph: REX

A black crocodile skin Hermès Birkin, a design so in demand, the venerable French fashion house recently reported a 23% jump in sales for the first three months of the year

This “hot new trend”, as with most, is, needless to say, nothing new, as in respect of the Birkin, British actress, activist and Gainsbourg muse Jane Birkin (b. 1946), after whom the style is named, typically laissez-faire in approach, described the pricey purse as “a very good rain hat; just put everything else in a plastic bag”. In his book Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change author W. David Marx explains that for luxury goods to function as status symbols, they need cachet in terms of an inherent association with high-status lifestyles, it’s not enough that the item in question, whether that be a watch, bracelet or bag, is used in and of itself to convey status. Someone such as Olsen carrying a beaten-up Hermès bag suggests, according to Marx, that they’re not wearing it simply because of the label, i.e. for status marking, and as such, it gives the brand a degree of fashion gravitas beyond mere price point. Of course, arguably, all trends start as a result of the combined influence of “outsiders” and “elites”, whereas the early adopters, Marx posits, are “well-paid (economic capital), well connected (social capital) and well educated (educational and cultural capital). Moreover, they’re cosmopolitan”. This “Upper Haute Bourgeoisie”, in the words of American writer Whit Stillman (b. 1952), by and large, prefer patina to stark, shiny newness, but as literary historian Paul Fussell (1924-2012) wryly observed forty years ago “as the middle class gets itself more deeply entangled in artistic experience, hazards multiply, like patina, a word it likes a lot but doesn’t realize is stressed on the first syllable.”

Perhaps of key interest, Marx suggests the prevalence of internet usage is “draining status value”, in the sense that, once upon a time elites could signal status through knowing certain facts for example, about wine or antiques; whereas now Wikipedia makes us all faux experts on anything from opera to twentieth-century literature and we can acquire a Picasso (1881-1973) or Jean-Michel Frank (1845-1941) armchair in only a few clicks. Similarly, “niche” (apropos brands, collectables or artists known only by a select few), is becoming a thing of the past. Marx gives an example of a New York Times article, that made reference to an unassuming high-top sneaker, worn by rifle-wielding Taliban insurgents. Called Cheetahs, they’re produced by Servis Shoes, Pakistan’s largest footwear manufacturer; marketed toward athletes, and once endorsed by celebrities they’re the company’s best-selling model. Hours after publication an editor at a major men’s fashion magazine, seemingly enamoured by the fundamentalists’ footwear of choice, tried, but failed, to buy them online — yet, within a matter of weeks, Pakistani e-commerce sites popped up, shipping the shoes worldwide. Ergo, as elites such as actors, models, artists and musicians are no longer able to exploit obscurity as means of signalling cultural superiority, thereby imbuing their inherent cachet on anything from Converse to Levi’s 501s (both of which have attained iconic status as a result of celebrity endorsement), vast swathes of “pure” indie culture are now entirely bereft of status value. The somewhat depressing result of such global democratisation is that “with obscurity itself a fleeting state, price reemerges as the most reliable signalling cost”.

As such, beaten-up Birkin’s can be seen as elites differentiating themselves from TikTok stars and influencers by showing they don’t care about an item’s inherent monetary value. This chimes with another increasing trend, namely, people using “alibis” as a means of justifying their actions, an idea taken from French sociologist Jean Baudrillard’s (1929-2007) The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures (1970). Sociologically speaking, the term “status” is used to describe an individual’s place in a hierarchy (an idea removed entirely from class diktats), in the sense that, every time we meet a stranger, we have to understand their status level, so that we know how to treat them. Essentially, those who have high status don’t need to signal as such, so every time an individual looks as if they’re trying to get status, they’re revealing they don’t actually have it; so it’s important, strategically, not to give away their hand. In essence, they need an alibi for their status-seeking actions. By and large, those carrying an Hermès Birkin do so because it’s a desirable, high-ticket item, the alibi is: “It’s just a bag, I don’t care if it gets scratched or knocked around.” Celebrities such as Julia Fox (b. 1990) are taking to TikTok in droves to champion their “beat-up” Birkin’s (hers, the victim of a machete attack, has been dubbed “the ultimate distressed Birkin” by W Magazine), and for every “influencer” handling their Hermès with kid gloves, there’s another championing a more free-spirited devil may care approach.

Of course, for those influencers set on making it a “trend”, the reasons might not be quite so clear cut; on resale platforms, the average price for a “fair” condition piece (i.e. showing significant signs of heavy wear) is 33% less than those in better condition — thereby making such “well-loved” carryalls the hypothetical “gateway drug” of luxury handbags. A similar trend can be seen in the rising popularity of $20 Apple wired headphones over $159 AirPods — with the lo-fi option becoming paradoxically something of a status symbol; with even celebrities such as Bella Hadid (b. 1996) and Lily-Rose Depp (b. 1999) opting for retro-tech over cutting edge accoutrements. “Whatever the reason, Hadid’s choice for flaunting those classic wires feels strangely luxurious,” proffers Vogue Writer Liana Satenstein. “The choice connotes that she can’t be bothered to keep up with the latest tech and prefers the simpler things in life, which is, oddly enough, the true measure of success.” Perhaps younger generations are tiring of the sort of gaudy, money-driven youth culture that has, by and large, permeated the past decade; and with any luck, we might see a return to individual style, where we celebrate uniqueness and character, as opposed to net worth, or rather, at least, the appearance of having a wardrobe full of luxury labels. In an internet-driven society where we’re used to instant gratification, it might be nice if terms such as “luxury” and “exclusivity” become associated once more with artisanal craftsmanship and originality, not merely the cachet of a big-name brand.