Nobody puts “Bébé” in the corner

Christian Bérard

“Listen carefully to first criticisms made of your work. Note just what it is about your work that critics don't like — then cultivate it. That's the only part of your work that's individual and worth keeping.” - Jean Cocteau

A noted painter, stage and costume designer, friend of Christian Dior (1905-1957), Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel (1883-1971) and Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941), all undisputed arbiters of Parisian elegance and savoir-faire, Christian “Bébé” Bérard (1902-1949) is a key figure in the canon of twentieth-century art. A darling of the fashionable and artistic set he was described by Vogue as a man “whose taste and originality influence the great couturiers more than any man today”, yet, he has, until recently, inexplicably perhaps, been largely ignored by historians and theorists of modern art. Something of a celebrity, it’s perhaps hard to over-egg, what has been variously described, as his “tramp-like” and “irresistibly comic” appearance; as immortalised by numerous notable photographers and artists, including Irving Penn (1917-2009), Cecil Beaton (1904-1980), Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) and Lucian Freud (1922-2011), to name but a few. Somewhat eccentric, to say the least, perhaps unusually, a number of these portraits were taken in bed, thus adding further to an already theatrical character, whose “torn suits, untucked shirts, messy beard” and flamboyant personality were inextricably intertwined with his set designs for theatre, as well as his décors for the homes of his friends and patrons. This was, after all, a time when the gentlemen of the haute bourgeoisie were impeccably dressed, with a penchant for Anglophilic dandyism. Frank for example, supposedly had forty identical double-breasted grey flannel suits, which he wore daily — unless attending costume balls, when he dressed in drag, usually in a white gown. It’s clear Bérard, who, according to Jean Cocteau (1889-1963), could be seen at Maxim’s “dressed in old faded overalls or in patched and colour-stained overalls”, with a rose or carnation pinned to his collar (seemingly thumbing his nose at the conventions of high society), had no desire whatsoever to fit in. Later in life, almost as if to add to his appearance of a “magnificent bum” — to borrow from the title of Jean-Pierre Pastori’s 2018 biography, Clochard Magnifique — Bérard was never seen without Jacinthe, a bichon frise and “dusty bundle of hair”, he thought looked like “an old Louis XV wig”, that he carried, or led around “by a string or a leash braided from old ties”. Yet, despite his portraying himself as a bearded and bedraggled entertainer, he was in fact a tortured and deeply troubled man; as close friend and confident Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) would later recall, “His filthiness fascinated me quite as much as his mind”.

The image Bérard portrayed was in and of itself a piece of fantastical make-believe. One might easily assume, looking at any one of the portraits taken of the artist that they were radical, in the sense of their revealing the true “real life” persona of an artist, warts and all, as it were, at a time when the image of public figures was highly controlled and stylised (a world away from the sort of au naturel “look” portrayed by fashionable photographers today). Yet, despite his posing in dilapidated hotel rooms, the nursing home where he was being treated for an Opium addiction, and in the smoking room of his apartment — always, seemingly, with stained wallpaper, and tables cluttered with newspaper clippings, piles of magazines and correspondence — attending social functions wearing dirty clothes, fingers black with paint, a shaggy beard and hair, Bérard was from a wealthy bourgeois family, born in Paris in the seventh arrondissement, to an architect father and a mother who had inherited a funeral home. By portraying himself thus, it linked him to those “eccentric modernists” who worked on the fringes of artistic circles, producing the sort of multidisciplinary, transnational works that came to define the early twentieth century French avant-garde. Indeed his relationship with the Parisian beau monde is somewhat hard to comprehend, as, despite his paint-spattered and tattered appearance, French writer Edmonde Charles-Roux (1920-2016) recalled how much time Bérard spent on the phone, giving fashion advice, which was considered indispensable (it was he who convinced French ballet dancer Zizi Jeanmaire (1924-2020) to cut her hair short, thus establishing her unforgettable style). In matters of taste he was so trusted, that when a fledgling Dior set up his couture house in 1946, Bérard advised him on the toile de Jouy decor that had such a profound and lasting impact on the brand’s visual identity: “He was often an inspiration for fashion designers of his time,” enthused Boris Kochno (1904-1990). “Gifted with an exceptional sense of sartorial elegance, in his conversations with his designer friends, Bérard used to suggest new ideas that very often served as the basis for their future collections.” Of course, when one considers Bérard’s appearance with modern eyes, it’s perhaps worth remembering, that it was a period of the twentieth century when there were massive advances in the arts, when people celebrated real talent and weren’t as easily duped by a superficial sheen of PR smoke and mirrors. One wonders how a character like Bérard would be perceived now, by a society that puts such emphasis on appearance, and shallow, eye-catching design, with the result that the truly gifted are often overlooked in favour of media-backed, trite mundanity.

Christian Bérard peainting “Les enfants des Goudes” at his easel (1941) from the collection of Pierre Passebon, photograph by André Ostier © Indivision A. et A. Ostier

Christian Bérard, Carnaval (1927) from the collection Juan Picornell, image c/o Nouveau Musée National de Monaco

Of all twentieth-century artistic luminaries, to Bérard there were two who were of fundamental importance, namely, Cocteau, one of the most enigmatic pioneers of the twentieth century (a multi-hyphenate poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic) and his partner, Boris Kochno, librettist and artistic director of the Ballets Russes; both of whom had an extensive network of friends and patrons from whom Bérard would benefit throughout his lifetime. It was via Cocteau that in the fall of 1926 Bérard first met Kochno, during a studio visit organised by despotic ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929). The planned project didn’t come to fruition, and it wasn’t until after the death of Diaghilev in 1929, that the two men would meet again, after which, they remained together until the end, leading an eccentric and colourful life of drug addiction and artistic exploration. Almost immediately, at Kochno’s insistence, Bérard began working on costumes and sets for the ballet La Nuit, that had been inspired by the librettist’s nocturnal walks, and simultaneously, on a portrait of Kochno — moving into a room of the family mansion, unused, supposedly on the basis of its being cursed, that was stripped of furniture and turned into a studio. “I posed for Bérard in a yellow satin jacket with a Pierrot collar, a disguise he had rented from a theatrical costumier which, later, in La Nuit, became the costume for an acrobat,” Kochno recalled in his biography. “For this portrait, Bérard used a canvas on which he had already painted a picture. But the new layer of paint did not make it disappear entirely, and the upside-down head of a character from the first composition remained visible at the bottom of the canvas, like a playing-card figure with a double image.” The portrait, which remained in Kochno’s possession until his death, displays signs of Bérard’s frenzied gesturally, and the way in which he rubbed and scratched at the paint, so much so that in places the raw canvas shows through. The pair soon moved into cheap rooms at the First Hôtel in the fifteenth arrondissement of Paris, which would remain home for the next decade, and where Bérard, in its cramped confines, would execute a large number of his works. “For years he lived in a small bedroom, several flights up in a somewhat squalid and liftless hotel,” bemoaned Beaton. “It was one of those hotels where people could sign the register (or not sign the register) and have a room in an hour. Bérard’s small den has a brass bed, a chair, a table, a yellow-stained cupboard, and a futuristic wallpaper of magenta roses. In this room he smoked opium, painted as he sat on the bed, and accumulated piles of books and magazines.” Indeed it was such a down-at-heel establishment that when Baron de Rothschild called, they hung up, assuming it to be a joke, and couldn’t believe their eyes when later that day his chauffeur turned up in a Rolls Royce asking as to the artist’s whereabouts.

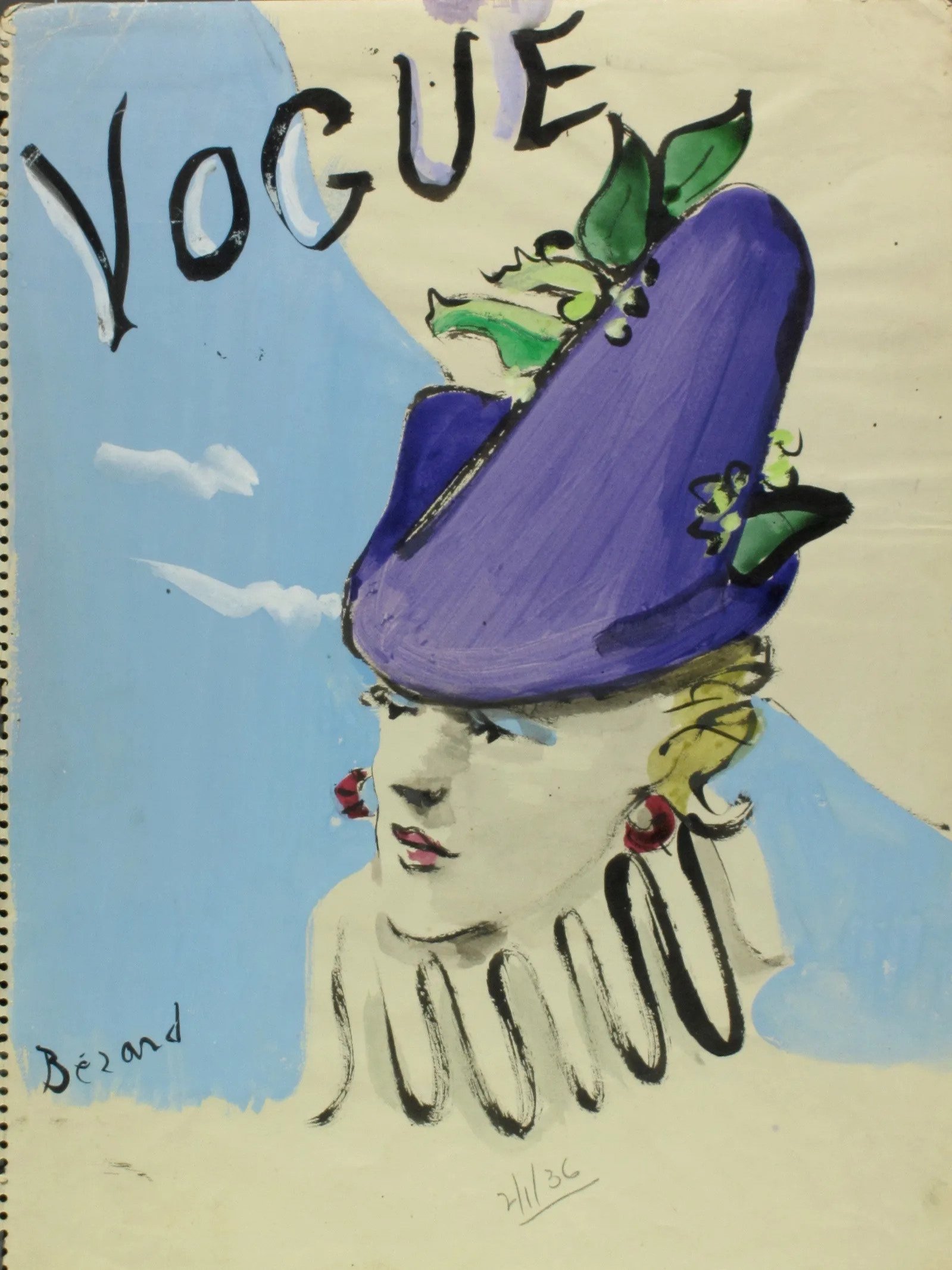

Cover art designed by Christian Bérard for Vogue magazine in February 1936, typical of the artist’s unique and much sought after style © Vogue

A portrait by Christian Bérard of his close friend and confident, couturier Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel (c. 1937) © Chanel/Christian Bérard

“Gypset” decades before New York Times journalist Julia Chaplin coined the phrase (to refer to an unconventional, bohemian approach to life), the trio were particularly fond of the Côte d’Azur and Monaco, where they joined a generation of young artists, poets and writers, including Christopher Wood (1901-1930), René Crevel (1900-1935), Francis Rose (1909-1979) and Georges Auric (1889-1983) et al, who gathered each summer at the Hôtel Welcome in Villefranche-sur-Mer. It was in its rooms that Cocteau first introduced Bérard to opium, an addiction from which neither would ever break free; the two forming an unbreakable bond, in part, as a result of this shared connivance, that ensnared so many of their artistic compatriots. “It was more than a friendship, [it was] one of these unconsummated, complicit and laughing liaisons specific to homosexuality,” wrote Claude Arnaud (b. 1955) in his biography of Cocteau. “The opium excited their irony by pushing them to concocting the most absurd characters … and when they weren’t plundering the attic for floral dressing gowns and antique hats worthy of Laure de Chevigné, to imitate old ladies going merrily to ruin themselves at the Casino in Monte Carlo, they became ageless old girls kicking their legs one last time at the Folies Bergère, before breaking in two.” Cocteau was working on the costumes for La Machine Infernale, which premiered in 1934 at the Theatre, Comedie des Champs Elysees, and he had the director, Louis Jouvet (1887-1951), hire Bérard to design sets. It was during the course of which, his first foray into the world of interiors, so to speak, that Bérard designed an extraordinary mural for Jouvet’s Parisian apartment, representing Oedipus and the Sphinx playing cards — its composition referencing both the work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) and Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) and demonstrating, at an early stage, the artist’s neoclassical inclinations. Seemingly spurred on by its success, later that year Cocteau, in collaboration with Bérard, painted his first mural for a masked ball in the loggia of Villa Blanche, Tamaris, on the French Riviera, the home of French playwright Édouard Bourdet (1887-1945), and his wife, the actress Denise Bourdet (1892-1967). The fresco, later destroyed, depicted a sailor, a mother and her daughter set against a skyline, as a way of, quite literally, bringing the exterior landscape inside. Whether or not the duo were pleased with the result, it would be another twenty years until Cocteau would once more venture into mural painting, this time at Francine Weisweiller’s (1916-2003) fabled Villa Santo Sospir, nestled at the tip of Cap Ferrat, between Nice and Monaco, where again, he chose to extend the stunning sea views onto the villa’s barren white walls. In the interim, Bérard continued in his exploration of the art and culture of classical antiquity, in a large décor painted for another of his patrons, art lover and collector Hélène Anavi, bringing the sunny Mediterranean landscape into her urbane Parisian apartment.

A wonderfully expressive self-portrait by Christian Bérard (1932) (detail), from the collection of Jean Hugo © Jean-Baptiste Hugo

During summers, when Kochno was away on tour with his company, Bérard went to Tamaris — the cradle of antiquity, a place of escape and creation — where, far away from Paris, he moved into a room at the Grand Hôtel, which he would turn into a studio, engaging in intensive personal correspondence; documenting not only the progress of his work, but his often wrought psychological and emotional state. These deeply personal missives were illustrated with charcoal or gouache drawings, especially at serious moments, for example, when in October 1932 he wrote: “Tamaris is dark, lifeless, it is cold and the room next door is utterly empty. The only beautiful thing is the light, there is a sunset that gets more beautiful every evening.” Whether or not a factor that can be attributed to the Mediterranean light, Bérard’s work undoubtedly reached new heights in Tamaris and around this time, under the Patronage of French decorator and maître of sophistication Jean-Michel Frank (1995-1941), he produced a number of spectacular works, including a portrait of collector and patron of the arts Marie-Laure de Noailles (1902-1970) and her daughter, Nathalie (1927-2004), to hang above the striking mica-clad fireplace in the main salon — or as Marie-Laure called it, the “Play Room” — of her fabled hôtel particulier on place des États-Unis. Immortalised on canvas, in Bérard’s immediately identifiable style, this touching portrait of mother and daughter only served to embellish the elegant parchment-clad decor, which had been designed by Frank as a backdrop to a jawdropping collection of contemporary and classical masterworks by the likes of Van Dyck (1599-1641), Goya (1746-1828), Juan Gris (1887-1927), Man Ray (1890-1976), Balthus (1908-2001), and Picasso (1881-1973). A jack of all trades, Bérard produced paintings, drawings, carpets, screens, rugs, tableware, tapestries, lampshades and planters, many of which were sold at Frank’s gallery on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, and found their way into the homes of such prestigious figures as Elsa Schiaparelli (1890-1973), Marie-Blanche de Polignac and Jean-Pierre Guerlain. Frank even had some of his designs in gouache transcribed onto fabric and leather by couture embroiderer Margarita Classen Smith, who acted as something of an intermediary in dialogue between Bérard and Frank, converting what French writer Colette (1873-1954) referred to as the artists “nonchalant hand” into more refined materials, the result of which was utterly breathtaking.

Something of a visionary, Frank was unusual in that he gathered around him a family of extraordinary artists to design furniture and objets d’art, including such avant-garde figures as Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), Salvador Dali (1904-1989), Emilio Terry (1890-1969), Jean Hugo (1894-1984) and Paul Rodoconachi (1871-1952), none of whom drew a line between art and decorative works. “For my livelihood, I accepted to make anonymous utilitarian objects for a decorator at that time, Jean-Michel Frank ... it was mostly not well-seen,” Giacometti explained in a 1962 interview with André Parinaud (1924-2006). “It was considered a kind of decline. I nevertheless tried to make the best possible vases, for example, and I realized I was developing a vase exactly as I would a sculpture and that there was no difference between what I called a sculpture and what was an object, a vase.” It’s clear Frank shared a certain simpatico will all those artists he worked with, and with Bérard, it was an instinct for emptiness, both figures oscillating between anguish and joie de vivre, and it was through that relationship, that the artist brought a world of colour into the designer’s minimally appointed creations. Despite a reputation for severe austerity, having been dismissed by a contemporary as the high priest of “rooms no one lived in”, black and white photographs can often be deceptive, and the Giacometti plasters seen in Frank’s gallery were painted tints of sky blue, pale yellow and terracotta, whilst lamps were topped with apple-green, cherry-red and lemon-yellow shades. Amongst his many talents, Bérard was an exceptional colourist, with a unique talent for reviving and recontextualizing eighteenth-century art de vivre, presenting it in such a way that was uniquely his own, expressing a singular artistic vision, which is both original, immediately identifiable, and yet, at the same time familiar, in the way in which it references the past. Again in collaboration with Frank, he would produce a series of screens for the apartment of Claire Artaud, featuring characters lying on large monochrome beaches in memory of the Cote d’Azur, which had an immeasurable impact on the artist’s creative sensibility. Indeed it was there that Bérard made his curious Album d’Intérieurs — a series of gouache drawings representing entirely fictitious, Degas-hued interiors — free inventions, where there’s just enough detail for the viewer to imagine a semblance of a decorated space. Entirely devoid of any human presence, Bérard adorns these rooms with motifs, once again, taken from the history of art, employing, for example, classical friezes and Greek key motifs. In one such interior, a curtained archway opens out onto a beach, both walls and floors covered in a stylised flower motif. Bérard would again employ such techniques when Frank commissioned him, a decade later, to design a carpet for the fabled Rockefeller apartment at 810 Fifth Avenue, New York, that would stand up to the richness and quality of his overall decorative scheme. By covering the floor in a colourful explosion of abstract sherbet-coloured flowers, set against a raspberry pink background (reminiscent of the sort of vivid tapestries seen in eighteenth-century apartments) Bérard was able to create harmony between the numerous works of art, including two ten-foot-tall monumental fireplace murals — by Matisse, Le Chant (1938), and Fernand Léger, Untitled (Fireplace Mural) (1939) — that stood either end of the grand salon.

An instillation by Nick Mauss, after Bérard’s designs for L’Institute Guerlain, at the current exhibition “Excentrique Bérard” at the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco, photograph Andrea Rossetti c/o NMNM

Bérard was undoubtedly an artist much in demand, caught up in a whirlwind of commissions, that he accepted more often than he should have, variously, out of friendship, need or quite simply, resignation. Yet many of his peers, who considered him to be one of the most gifted painters of their generation, castigated him for such frequent forays into what they saw to be the “minor” arts of fashion, theatre and decor. American composer Virgil Thompson (1896-1989), a close friend and collaborator, believed Bérard “would lead his art into paths of humane awareness, as Goya had done”, but that the artist faltered in proceeding along a path unworthy of his talent. “He did not, he could not, persist as in France Degas had persisted, and Renoir and Monet and Bonnard. So he made stage designs. These were beautiful and appropriate. But all who were touched by his painting, especially his painting of people, came to regret … that he had not been able to live up to his genius.” Seemingly, at least in Thompson’s estimation, Bérard never matured as an artist, an opinion shared by countless contemporaries. “It was the applause that led Bérard to success, with eyes closed, and prevented him from seeing the canvases he wanted to paint,” so lamented American writer Julien green (1900-1998). “Each of his decorations was a delight, but how many paintings have they deprived us of?” It was a sentiment echoed by Cocteau who wrote: “If he had not let himself be seduced by the fashions he created for his designer friends, he would have been a great painter.” By the late 1940s, well known in New York as the set designer for a popular production of Jean Giradoux’ (1882-1944) Le Folle de Chaillot — an act of cultural diplomacy the New York Times billed a “Fashion Pageant from Paris” and brought Americans what they “sorely missed during the war — French art and fashions” — audiences across the pond were far more accepting of Bérard’s multi-hyphenate proclivities, with a 1947 article in Art News, almost prophetic of the principles that would come to define the mid-twentieth century Pop Art movement, reporting: “As if in defiance of the Puritan mistrust of the Jack-of-all-trades, Bérard can juggle his talents … Even if at some point he designs a toothpaste tube, it will immediately be recognisable as Bérard.”

In 1936, seemingly weary of his cramped, ragtag room at the First Hôtel, Bérard moved into an apartment on rue Casimir-Delavigne, in the heart of the Latin Quarter, where he lived with Kochno until his death in 1949, at the age of forty-six, having become, in the word’s of Christian Dior, “one of the leading painters of the time.” In stark contrast to his earlier, somewhat less salubrious abode, views by cityscape painter Alexander Serebriakov (1907-1994) show a plush bourgeois interior, hung with an array of contemporary art, including Edgar Degas’ (1834-1917) Two Men (c. 1865-69), as well as drawings by Picasso and Matisse. Somewhat graphic in its simplicity, Bérard’s room was lined in pink and red stripe fabric in homage to the foyer of the Covent Garden Opera House — where the bedside lamp stayed on night and day. Yet, despite such luxuries, the city would never be as agreeable to Bérard as the South of France, writing to Kochno, who at the time was staying at Mas de Forques in Lunel near Montpellier: “Paris is a foul. Gloomy city. How difficult your letters are when one is in Paris and dreaming of rest and sun.” After his death in an interview for Vogue magazine writer Colette recalled a time when they were neighbours, during the war: “He had carved out for himself at the Hôtel du Beaujolais a temporary dwelling, made to his measure and according to his fancy, the rooms loaded with statues and garlands, the partitions plonked down at random, cutting things in two, torso here and buttocks there, monumental deities … it was very rare that between ten and noon one, two windows of the Beaujolais frontage did not open wide, to show the sight, stretching his arms, of Bérard in pyjamas. Bérard in a bathrobe, in his shirt, Bérard dazzled every day, as I was to welcome in his eyes of mossed agate the spectacle of the garden plumed with gushing waters … ‘I’m coming down!’ he would shout to me. In fact, he rarely did come down. He was already working.” Already by the 1960s, Bérard’s work had been largely forgotten, and art gallerist and collector Alexandre Iolas (1908-1987) was one of the few to still champion his work. Once so ubiquitous, Bérard’s name was slowly excised from the salons of high society until it was almost forgotten. As art historian Jean Clair (b. 1940) succinctly puts it: “In the official annals of modern art, Bérard’s name is missing. Or nearly so: sometimes he is mentioned in passing.” The incredibly varied nature of Bérard’s output makes him as an artist somewhat unclassifiable, and whether or not such a trivial matter of art-historic nuance in any way contributed to his fall from grace, it’s sad but true, that however remarkable an artist, without someone to pass the baton, they can very easily lapse into obscurity. Now, with a new exhibition in Monaco, Bérard’s name is once again tripping off the lips of the chattering classes. If we look at the entirety of the artist’s extraordinary oeuvre, rather than trying to pigeonhole it, or fit it into some sort of mould that we think he as an artist should be, we should remember him simply as a humanist, whose work, whether it be a drawing, play or painting, still has the power to move us today.

Ben Weaver

The exhibition, “Christian Bérard: Excentrique Bébé” is on at the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco until 16 October 2022