The Unknown Giacometti

Surrealism and sadism

“In every work of art the subject is primordial, whether the artist knows it or not. The measure of the formal qualities is only a sign of the measure of the artist's obsession with his subject; the form is always in proportion to the obsession.” — Alberto Giacometti

When one thinks of Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), the image that immediately springs to mind is that of his arresting post-war works, expressing the deepest of human concerns; extraordinary sculptures of frail, impossibly elongated figures, weathered and emaciated, with the weight of the world manifest in the emptiness around them. The artist’s austere Walking Man (1947), Giacometti’s first large figure of its kind, was perceived by contemporaries as an almost sacred statue, in the sense of its being seen as a monument to the unyielding spirit of Auschwitz victims. Such works have often been compared to that of the Existentialists in literature, in the sense of their defining the place and purpose of man in a godless universe. French philosopher, novelist and playwright Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) described Giacometti’s endeavour as “to give sensible expression” to “pure presence”, referring to his 1947 sculpture L’homme au doigt (Pointing Man) as “always halfway between nothingness and being”. Giacometti’s appreciation for the human form, however, came some years earlier, when the artist first moved to the French capital in 1922 to train under French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929) at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. There he was inspired by the Cubism of Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), as well as exposure to non-western art, in particular, traditional African and Oceanic sculpture, whose use of abstraction over naturalistic representation appealed to a Parisian avant-garde breaking away from traditional “Western” painting styles. However, it was Giacometti’s acquaintance with artists such as Max Ernst (1891-1976) and Joan Miró (1893-1983) that brought about a turning point in his creativity. The Swiss sculptor became increasingly interested in Dada-ism’s rejection of dogma, text and doctrine, and in terms of his own abstract work, he very quickly formed a distinct visual language that held complex messages tied to universal themes of love, death, gender and sex. Already by 1930, the then relatively unknown artist caught the attention of André Breton (1896-1966), co-founder, leader and principal theorist of the Surrealist group. Originating as a literary movement in the late 1910s and early 1920s, Surrealism sought to revolutionise the human experience, balancing a rational vision of life with one that asserts the power of the unconscious and dreams. It was defined by Breton in his 1924 Manifeste du surréalisme (Surrealist Manifesto) as “pure psychic automatism, by which it is intended to express … the real process of thought. It is the dictation of thought, free from any control by the reason and of any aesthetic or moral preoccupation”. At an exhibition organized by gallery owner Pierre Loeb (1897-1964), Giacometti’s Boule suspendue (Suspended Ball) (1930-31) caused such a furore in Breton’s circle of artists and writers that he purchased the work immediately. A few days later he propositioned Giacometti at his cramped Montparnasse studio, extending him an invitation to join the Surrealist movement. Despite warnings against Breton and the influence he exerted over the group, the Swiss sculptor joined largely through curiosity, and under their influence, soon found himself fascinated by the dark side of the human psyche.

Man Ray’s “Woman Holding the Disagreeable Object” (1933), the Surrealist wooden sculpture created by Giacometti in 1931, photograph, © Man Ray Trust ADAGP 2019

“Cage” (1930-1931) by Alberto Giacometti, wood, 49.8 x 27 x 27 cm, Moderna Musset, Stockholm; photo: Prallan Allsten, © Succession Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti Paris + ADAGP) Paris 2019

In terms of formative experiences, since arriving in Paris, Giacometti had, essentially, been immersed in libertinism; including a tempestuous relationship with Denise Maisonneuve, who shared his interest in surrealism and introduced him to the violent, transgressive work of French poet Isidore Ducasse (1846-1870) (self-styled as the Comte de Lautréamont), whose writings had a radical influence on modern arts and literature. It’s perhaps worth remembering, Giacometti came from a society that held very conservative views, and men of his generation were brought up in the polarised belief that women were either Madonna’s or whores. As an adolescent, the Swiss sculptor had been rendered infertile following an attack of mumps, as well as partly impotent. The solution, as he saw it, was to have detached sex with prostitutes, whom he could not disappoint, which again, had the effect of colouring his attitude toward the opposite sex. In tune with a rapidly changing world, Lautréamont’s provocation of a sight “as beautiful as a chance encounter between an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table” can be seen as anxiety about the modern condition, translated into fetishism that inspired many Surrealists; the umbrella is male, the sewing machine female and the dissecting table a bed, thus evoking ideas of mechanistic cruelty and emotionless sex — something which inevitably, given personal circumstance, would have spoken to the young Giacometti. Indeed one can see how the artist’s depictions of female models tend to divide along the classic Madonna/whore cliche; there’s the Madonna-goddess Isabel Rawsthorne (1912-1992), the whore Rita Gueyfier and the virgin Flora Mayo — only with Annette Arm (who became the artist’s wife, after his return to Switzerland in 1942), was he able to move beyond that dichotomy. Filmmaker and photographer Eli Lotar (1905-1969) was Giacometti’s last male model. In the postwar years, he became destitute, living off the generosity of friends like Giacometti, who gave him money in exchange for running small errands and posing. In Giacometti’s three busts of Lotar, which evoke Mesoamerican and Egyptian statuary, the man who became a tramp was given the dignity of a priest. The artist was once asked by French novelist Jean Genet (1910-1986) why it was that he approached men and women differently; he admitted that it was because he didn’t understand women and that they seemed more remote. Genet noted that, for Giacometti, whereas women were sometimes depicted as goddesses, men were priests “belonging to a very senior clergy”, all of them depending “invariably on the same haughty and gloomy family. Familiar and very close. Inaccessible.”

“Woman with Her Throat Cut” (1932) by Alberto Giacometti, bronze, Fondation Giacometti, Paris, © Succession Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti Paris + ADAGP) Paris 2019

“Point to the Eye” (1931-32) by Alberto Giacometti, plaster, partial reconstruction © Succession Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti Paris + ADAGP) Paris 2019

In 1933, while grieving the death of his father, prompted by Breton, Giacometti engrossed himself in the bibliography of the Marquis de Sade (1740-1814), becoming increasingly preoccupied with ideas of seduction, idolatry, and fetishism; indeed that same year, the artist wrote two texts detailing fantasies of murder and rape for the magazine Le Surrealisme au Service de la Revolution (Surrealism in the service of the revolution), a periodical distributed by the surrealist group in Paris. Sade was many things, a self-proclaimed paedophile, rapist, torturer, and an eloquent literary apologist for sexual cruelty, who wrote pornographic novels set in ancien régime France. In the years following his death, the writer’s name — quite literally enshrined in the very concept of “Sadism” — was practically erased from cultural memory; then in the early twentieth century, poet Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) and then French editor Maurice Heine (1884-1940) helped publish, and also republish, Sade’s long-suppressed texts, including a first-ever edition of the colossal Les 120 journées de Sodome ou l’école du libertinage (The 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinage) (1904) (penned in 1785 while imprisoned in the Bastille for a series of sexual scandals, the continuous, twelve-meter-long scroll, described by Sade as “the most impure tale ever written since the world began”, was hidden in his cell walls and later found when the jail was stormed during the revolution) and a newly unearthed, original version of Justine (1930). Since their inception intellectuals and anarchists have been particularly sensitive to Sade’s writings, and the Surrealists were no exception. Apollinaire called him “the freest spirit that has ever existed”, and it was freedom of imagination and instinct, that was at the heart of Surrealism. Despite the deeply disturbing and predatory nature of Sade’s sexual politics, the libertine philosopher fascinated Giacometti and his friends, among them Georges Bataille (1897-1962), André Masson (1896-1987), Luis Buñuel (1900-1983), and Salvador Dalí (1904-1989). The revival of Sade’s writings, to a large extent, served an incitement for the Surrealist movement — first as the dissidents gathered around Bataille, then the group led by Breton, which, to some extent, can be seen as an informal “sadist circle”, with the Marquis’ name soon serving as a password amongst the Parisian bohème.

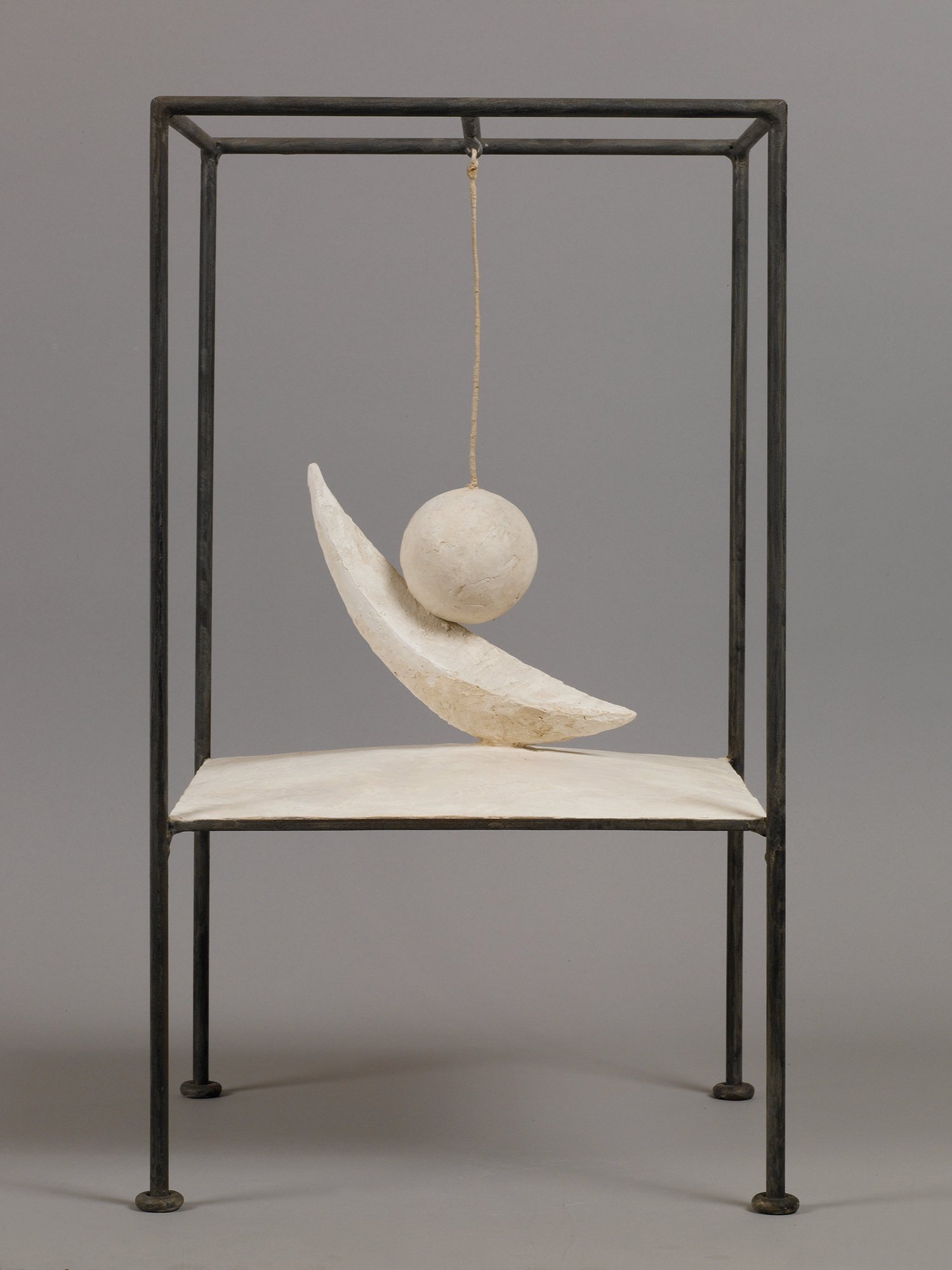

“Suspended Ball” (1930-31) by Alberto Giacometti, Fondation Giacometti, Paris, © Succession Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti Paris + ADAGP) Paris 2019

The sculptures Giacometti created during this period mark a key phase in the artist’s career, appearing dreamlike and hallucinatory, puzzling and metaphorical, even unsparingly barbarous, they reflect the artist’s psychological state at the time. Though Sade’s writings on violence and sadism clearly spoke to Giacometti, the artist’s affection for scenes of brutality emerged even before discovering them; as a teenager, and throughout his formative years, his sketchbooks show a growing fascination with cruelty, notably in copies of religious subjects representing scenes of violence. In 1913, at the age of twelve, he was making drawings of St. Sebastian’s martyrdom, his diary of 1923 contains a sketch of an undressed man on his knees talking to a priest on the verge of execution, and in one of his numerous undated notebooks are scenes of torture he planned to turn into sculptures and a drawing of a naked woman strangled from behind by a Fantômas-like maniac. However, it was from 1933 onwards that the artist infused his sculptures and works on paper with a perverse eroticism that came closer to the libertine philosopher’s depraved universe. References to Sade’s name appeared numerous times in Giacometti’s notebooks, alongside drawings of sculptures with strong erotic content — schematising the sexual organs or representing scenes of voyeurism and prostitution. This was a pivotal moment, expressing tensions between, on the one hand, the representation of his often-violent fantasies, and on the other, a lingering desire to return to the representation of reality. In terms of translating such drawings into three-dimensional sculpture, the artist abandoned naturalism for a symbolic or suggestive rather than literal interpretation of sexual intercourse/penetration (seen by the Surrealists as a struggle between the sexes), rape and at times murder (the culmination of Sadian pleasure in which sexual impulses are freed so that pleasure and death can coincide). The body is represented in an allusive way, through an organic detail or in a shape simultaneously both animal and vegetal. Though far less extreme than his diary sketches, the series of striking, psychologically-charged sculptures created during this period, are nevertheless impregnated with vicious, often fetishist imagery.

Somewhat perplexing, although entirely in line with the Surrealist mantra, Giacometti would later claim of these often macabre sculptures, that they developed “independently” of him, and that prior to their realization, he conjured them up in their entirety before his inner eyes. Homme et femme (Man and Woman) (1928–29), and the obviously phallic Objet désagréable (Disagreeable Object) (1931), are both works made during the height of the Swiss sculptor’s Surrealist participation, both of which embrace ambiguity in terms of their evocations of impending penetration. In the former “man” appears to be represented by a phallic extension, whereas “woman” takes the form of a concave vessel, representing a disjointed, geometric tableau of copulation. The latter, essentially, a mace-like wooden phallus, shifts into a more intimate register, poised between usefulness and uselessness, seduction and terror. First designed in plaster for its translation into wood, it wasn’t until 1961 that Objet désagréable was translated into bronze (coinciding with a period from the mid-nineteen fifties when Giacometti’s surrealist works experienced a resurgence of interest), described variously by the artist as “objet” or “objet sans base I”. The photograph taken by Man Ray (1890-1976), depicting a topless Émilie Carlu (aka “Lili”) tenderly cradling the enormous Objet désagréable between her bare breasts and against her shoulder — as one might do an infant — quite possibly relates to the name Embryon (Embryo) that Giacometti gave in his notebooks to a variant of Objet désagréable executed in marble.

A number of the artist’s abstract surrealist works reference latent sexuality and bodily contact using totemic motifs taken from ethnographic art. Pointe à lʼœil (Point to the Eye) (1931-32) sees a long, tusk-like shank of plaster, teetering on a metal pin, whose stiletto point thrusts directly towards the eye socket of a miniaturised skull-like head, so as to “incite active, if only imaginary, participation”, in the words of a 2001 MoMA catalogue (The piercing of an eye was a theme popular with the Surrealists, most famously in the scene of a razor blade slicing a woman’s eye in the film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog), directed by Luis Buñuel (1900-1983) and written by Dalí). It could also be seen as an abstract representation of visual longing, in which the tapered baton traces the trajectory of the gaze. Similarly, in Suspended Ball, an evocation of foreplay, a sphere suspended within a metal frame hovers close to — but never makes contact with — a supine crescent. Dalí (1904-1989) described it as “a wooden ball, stamped with a feminine groove … suspended by a violin string over a crescent the wedge of which barely grazes the cavity. The spectator finds himself instinctively compelled to slide the ball up and down the ridge, but the length of string does not allow full contact.” In essence, as Dalí notes, Suspended Ball is intended as a tease.

“Standing Woman” (c. 1952) by Alberto Giacometti, Fondation Giacometti, Paris, © Succession Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti Paris + ADAGP) Paris 2019

However, it was Sade’s link between homicidal impulse and copulation that informed some of Giacometti’s most disturbing works. “There is no better way to know death,” the Marquis wrote, “than to link it with some licentious image”. In 1932 the Swiss visionary made a particularly vicious and perplexing sculpture, Femme égorgée (Woman with Her Throat Cut), representing a woman who has been raped and murdered: her jugular-vein cut, the body splayed open, disembowelled, arched in a paroxysm of sex and death. The memory of violence is frozen in the rigidity of rigor mortis. (Interestingly, in two of Giacometti’s preparatory sketches Eros, the Greek god of love and sex, and Thanatos, the personification of death, seen here as a single theme, are distinguished and treated separately.) The psychological torment and the sadistic misogyny projected by this sculpture, in stark contrast to the serenity of some of the artist’s better-known contemporaneous pieces, are a reflection of the Surrealists’ fixation with the irrational, sexual duality and archetypes. A thematic recurrence throughout Giacometti’s surrealist works, the female, seen simultaneously in horror and longing, as both the victim and victimiser of male sexuality, is often insect-like in form. Indeed the thin stomach and bulbous breasts of Femme égorgée bring to mind the praying mantis — an insect revered by the Surrealists because of the tendency of the female to devour the male during or directly after the sexual act (sometimes she decapitates the male at its start, his body performing his duty automatically, like a “sex machine”, again linking back to Lautréamont’s philosophical and poetic writings). Breton and his Surrealist co-founder Paul Éluard (1895-1952) cultivated mantes in their homes, inviting guests to observe the spectacle of their macabre sexual rites. Éluard even went as far as to tell French literary critic Roger Caillois (1913-1978) that their sexual act represented the ideal relationship — diminishing the male and magnifying the female — making it completely natural, he postulated, for the female to take advantage of her momentary superiority and kill the male.

The Surrealists mixing of experience, memory and philosophical bent drew heavily on the writings of Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud (1836-1939), whose map of the psyche placed the ego (the Ich, the I) at a point between the civilizing super-ego and the primitive libidinous id. Breton believed the exploration of the unconscious mind through art could free an individual from the restrictive shackles of bourgeois society, as well as morality and religion, so as to give expression to long-submerged desires, exploring the connection between death and sexual excitement. “The domain of eroticism”, wrote Bataille, “is the domain of violence, of violation … the most violent thing of all for us is death which jerks us out of a tenacious obsession with the lastingness of the discontinuous being.” In 1932, continuing his exploration into the pleasures of pain, Giacometti carved an amputated hand from wood and made a small painting of a Medieval torture chamber. And hereof, the subject of sadism suddenly evaporates from his practice. Just as the Swiss sculptor was finding fame as a Surrealist, he grew increasingly frustrated with the movement’s more eccentric escapades, and turning his back on this particular thread of modernism, he applied himself with wholehearted gusto to figural representation; in particular, he became obsessed with attempting to render the head, which he deemed an object unknown and without dimensions.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, Breton and his fellow Surrealists met Giacometti’s newfound passion with nothing but unbridled contempt and hostility. When Breton went to visit the Swiss sculptor at his studio, he was frustrated to see him working once again from “the visible”. When the artist tried to explain to him why he was working “from nature”, Breton flew into a rage, screaming: “A head? A head? Everybody knows what a head looks like!” Then in 1934 when Giacometti accepted a private commission, it proved the straw that broke the camels back. Breton saw it as Giacometti tying himself definitively to the bourgeoisie and excommunicated him immediately from the group. From this metamorphosis, a new, much more tempered, sober Giacometti was born. Despite cutting ties with the Surrealists, the artist’s later, spindly sculptures are still rooted in the physicality of the archetypal male and female, a theme he continued to investigate, albeit in a very different manner, for the rest of his career. Christian Alandete, Artistic Director of the Giacometti Institute in Paris has even suggested that the way in which the Swiss sculptor gouged out clay with a penknife to form the eyes of his elongated figures and incised their bodies was related to Sade’s slashing of his victims. Essentially, Giacometti was an artist whose commitment to plastic integrity was too independent, and too ingrained to be fundamentally altered by Surrealist doctrines. As such, if we look at the totality of the artist’s unique oeuvre, the lesson we might take away is that Surrealism and modern figurative sculpture needn’t necessarily be mutually exclusive domains.